| 120. Manifestations of Karma: The Relationships Between Karma and Accidents

21 May 1910, Hanover Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| The astral body was then our most exalted member, and our consciousness then was such as can to-day be compared only with our dream consciousness which is a survival of the past. But we must not think of the present dream consciousness, but one in which the dream images represent realities. If we study the dream as it is to-day, we shall find in its manifold images much that is chaotic, because our present dream consciousness is an ancient inheritance. |

| We meet here a third degree of consciousness infinitely more vague, which does not attain to the clarity even of today's dream consciousness. It is quite a mistake to believe that we are devoid of consciousness when we sleep. |

| 120. Manifestations of Karma: The Relationships Between Karma and Accidents

21 May 1910, Hanover Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

It is easily understood that karmic law can operate when, in the sense demonstrated, a cause of illness asserts itself from within man. But it is more difficult to understand that the experiences and actions of a previous life brought in by the individual at birth can provoke such illnesses as are the result of exterior causes—such illnesses as science calls infections. Nevertheless, if we go deeper into the true nature of karma, we shall learn not merely to understand how these external causes can be related to the experiences and deeds of earlier lives, but we shall also learn that accidents which befall us, events which we are prone to describe as chance, may stand in a definite relationship with the course of a previous life. We must indeed penetrate somewhat deeper into the whole nature of man's being if we wish to understand the conditions that are so veiled by our human outlook. We saw yesterday how chance or accident always presents the external event in a veiled form, because in those instances where we speak of chance, the external deceptions created by the ahrimanic powers are the greatest possible. Now let us examine in detail how such accidents, that is to say those events that are generally called ‘accidents,’ come about. Here it is necessary to bear in mind the law, the truth—the recognition that in life much of what we describe as ‘arising from within,’ or as ‘derived from the inner being of man’ is already clothed in illusion, because if we truly rise above illusion, we find that much of what we at first believe to have originated within man must be described as streaming in from outside. We always encounter this when we have to deal with those dispositions, those traits of character, which are summed up under the name of ‘hereditary characteristics.’ It seems as though these hereditary characteristics are a part of us only because our forbears had them, and it may appear to us in the most eminent degree as though they had fallen to our lot through no fault of our own, and without our co-operation. It is easy to arrive at a mistaken distinction between what we have brought from earlier incarnations and what we have inherited from our parents and forbears. When we reincarnate we do not come haphazard to such and such parents or to such and such a country. There is operating here a motive allied to our innermost being. Even in those hereditary characteristics which have nothing to do with illness, we must not assume anything haphazard. In the case of a family such as Bach's for instance, there were for many generations again and again more or less renowned musicians born (there were more than twenty more or less renowned musicians in Bach's family). We might well believe that this has purely to do with the line of heredity, that the characteristics are inherited from the forbears, and that as such characteristics are there, certain tendencies towards musical talent brought over from a previous incarnation will be unfolded. This is not so however; the facts are quite different. Suppose that someone has the opportunity of receiving many musical impressions in a life between birth and death, that these musical impressions pass by him in this life, simply for the reason that he has not a musical ear. Other impressions which he receives in this life do not pass by him in the same way, because he has organs so formed that he can transform the experiences and impressions into capacities of his own. Here we can say that a person has impressions in the course of his life which are capable of being transformed into capacities and talents through the disposition which he has brought with him from his last birth; and he has other impressions, which on account of his general karma, because he has not received the suitable powers, he cannot transform into the corresponding capacities. They remain, they are stored up, and in the period between death and a new birth they are converted into the particular tendency to be expressed in the next incarnation. And this tendency leads the person to seek for reincarnation in a particular family which can provide him with the suitable organs. Thus if someone has received a great many musical impressions, and because of an unmusical ear, he was unable to transform them into musical capacities or enjoyment, this incapacity will be connected with the tendency in his soul to come into a family where he will inherit a musical ear. From this we shall now see that if a certain family inherits a certain construction of the ear—which can be inherited just as well as the external form of the nose—all those individuals who in consequence of their former incarnation long for a musical ear, will strive to come into this family. From this we see that, in fact, a person has not inherited a musical ear or a similar gift in a particular incarnation. ‘by chance,’ but that he has looked for and actually sought for the inherited characteristic. If we observe such a person from the moment of his birth, it will seem to us as though the musical sense were within him, a quality of his inner being. If, however, we extend our investigation to the time before his birth, we shall find that the musical ear for which he had to seek is something that has come to him from outside. Before his birth or conception the musical ear was not within him. There was only an impulse urging him to acquire such an ear. In this case man has drawn to himself something external. Before reincarnation the feature which is later termed hereditary was something external. It approached man, and he hastened to take it. At the moment of incarnation it became internal, and made its appearance within. Thus, in speaking of hereditary disposition, we suffer from a delusion, because we do not take into account the time when the inner quality was an external one. Let us now enquire whether an external event occurring between birth and death, might not be the same as the case we have just now been discussing—whether it might be capable of being transformed into something internal. We cannot reply to this question without examining still more closely the nature of sickness and health. (We have given many instances in order to characterise sickness and health. And you know that I do not define, but try little by little to describe things, and to add ever more characteristics, so that they may gradually become comprehensible. So let us now add some more characteristics to those we have already collected.) We must compare sickness and health with something that appears in normal life, namely, sleeping and waking, and we shall then find something of still greater significance. What is taking place within a human being when the daily states of sleeping and waking succeed one another? We know that when we sleep, the physical and the etheric body are abandoned by the astral body and the Ego, and that the awakening is a return of the astral body and Ego to the physical and etheric body. Every morning on waking, all that constitutes our inner being—astral body and Ego—dives down again into our physical and etheric bodies. What happens with regard to those experiences which a human being has when going to sleep and when awakening? If we consider the moment of going to sleep, we see that all experiences which from morning to night fluctuated in our lives, especially the psychic experiences of joy and sorrow, happiness and pain, passions, imaginations, and so forth, sink down into the subconscious. In normal life, when asleep, we ourselves are unconscious. Why do we lose consciousness when we fall asleep? We know that during the state of sleep we are surrounded by a spiritual world, just as in the waking state we are surrounded by things and facts of the physical world of the senses. Why do we not perceive this spiritual world? Because in normal life to see the spiritual facts and spiritual things surrounding us at the present stage of human development between going to sleep and awakening, would prove dangerous in the highest degree. If the person were today to pass over consciously into the world which surrounds us between going to sleep and awakening, his astral body which gained its full development in the Ancient Moon period, would flow out into the spiritual world, but this could not be done by the Ego, which can be developed only during the Earth period, and which will have completed its Evolution at the end of the Earth period. The Ego is not sufficiently developed to be able to unfold the whole of its activity between falling asleep and awakening. If we were to fall asleep consciously, the condition of our Ego could be illustrated as follows. Let us suppose that we have a small drop of coloured liquid; we drop this into a basin of water and allow it to mix. The colour of that small drop will no more be seen because it has mixed with the whole mass of the water. Something of this nature happens when man in falling asleep leaves his physical and etheric bodies. The latter principles are those which hold together the whole of the human being. As soon as the astral body and Ego leave the two lower principles, they disperse in all directions, impelled always by this principle of expansion. Thus it would happen that the Ego would be dissolved, and we should indeed be able to envisage the pictures of the spiritual world, but should not be able to understand them by means of those forces which only the Ego can bring to bear—the forces of discernment, insight, and so forth—in short, with the consciousness we apply to ordinary life. For the Ego would be dissolved and we should be frenzied, torn hither and thither, swimming without individuality and without direction in the sea of astral events and impressions. For this reason, because in the case of the normal person the Ego is not sufficiently strong, it reacts upon the astral body and prevents it from entering consciously the spiritual world which is its true home, until there comes a time when the Ego will be able to accompany the astral body wherever it may penetrate. Thus there is a good reason for our losing consciousness when we fall asleep, for if it were otherwise, we should not be able to maintain our Ego. We shall be able sufficiently to maintain it only when our Earth evolution is achieved. That is why we are prevented from unfolding the consciousness of our astral body. The very reverse takes place when we awaken. When we awaken and sink down into our physical and etheric bodies, we ought in reality to experience their inner nature. But this does not happen, for at the moment of waking we are prevented from regarding the inner nature of our corporeal being, because our attention is immediately directed to external events. Neither our faculty of sight nor our faculty of perception is directed towards penetration of the inner being, but is distracted by the external world. If we were immediately to apply ourselves to our inner being, there would be an exact reversal of the situation that would occur if we fell asleep and entered the spiritual world with our ordinary consciousness. Everything spiritual that we had acquired through our Ego in the course of our Earth life would then concentrate, and after our re-entry into the physical and etheric bodies, it would act upon them most powerfully, bringing about a tremendous increase of our egotism. We should sink down with our Ego; and all the passions, the desires, the greed, and the egotism of which we are capable would be concentrated within this Ego. All this egotism would pour away into the life of the senses. So that this may not happen we are distracted by the external world, and are not permitted to penetrate our inner being with our consciousness. That this is so can be confirmed from the reports of those mystics who attempted really to penetrate the inner being of man. Let us consider Meister Eckhart, Johannes Tauler, and other mystics of the Middle Ages, who in order to descend into their own inner being dedicated themselves to a state in which their attention and interest was entirely turned away from the external world. Let us read the biographies of many Saints and Mystics who tried to descend into their inner selves. What was their experience? Temptations, tribulations, and similar experiences which they have depicted in vivid colours. These were compressed in the astral body and Ego, and made themselves felt as opposing forces. That is why all those who as Mystics have attempted to descend into the inner self found that the further they descended, the more were they impelled to an extinguishing of their Ego. Meister Eckhart found an excellent word to describe this descending into his own inner self. He speaks of ‘Ent Werdung,’ that is to say the extinction of the Ego. And we read in “;The Theologia Germanica”; (German Theology) how the author describes the mystic path into the inner human being, and how he insists that he who wishes to descend will act no longer through his own Ego, but that Christ with Whom he is fully permeated, will act within him. Such Mystics sought to extinguish their Ego. Not they themselves, but Christ within them should think, feel, and will, so that there may not emerge what dwells within them in the form of passion, desire and greed, but rather that which streams into them as Christ. That is why St. Paul says ‘Not I, but Christ in me.’ We can describe the processes of awakening and falling asleep as inner experiences of the human being: awakening as a sinking down of the compressed Ego into the corporeality of man, and falling asleep as a liberation from consciousness, because we are not yet ready to see that world into which we penetrate on falling asleep. Through this we understand waking and sleeping in the same sense in which we understand many other things in this world, as a permeation by one another of the various members of the human entity. If we consider a waking person from this point of view, we shall say that in him are present the four members of the human entity, the physical body, etheric body, astral body, and the Ego, and that they are linked together in a certain way. What results from this? The fact of ‘being awake.’ For we could not be awake were we not so to descend into our corporeality that our attention is distracted by the external world. Whether we are awake or not depends upon a certain regulated co-operation of our four members. And again, whether we are asleep or not depends upon the proper separation of our four members. It is not enough to say that we consist of physical body, etheric body, astral body, and Ego, for we understand man only when we know to what extent the various members are linked together in a certain state, and how intimately they are connected. This is necessary to an understanding of human nature. Now let us examine how these four members of man are linked together in the case of a normal person. Let us set out from the standpoint that the condition of man when awake is the normal condition. Most of us will remember that the consciousness we at present possess as earth-men between birth and death, is only one of the possible forms of consciousness. If, for instance, we study ‘Occult Science,’ we shall see that our present consciousness is a stage among seven different stages of consciousness, and that this consciousness which we possess today developed out of three other preceding stages of consciousness, and that it will at a later period develop into three other succeeding forms of consciousness. When we were Moon beings we had not yet an Ego. The Ego became united with man only during the Earth period. That is why we could not gain our present consciousness before the Earth period. Such a consciousness as we have today between birth and death, presumes that the Ego co-operates with the other three members exactly as it is doing today and is the most exalted of the four members of the human entity. Before we were impregnated with the Ego we comprised only physical body, etheric body, and astral body. The astral body was then our most exalted member, and our consciousness then was such as can to-day be compared only with our dream consciousness which is a survival of the past. But we must not think of the present dream consciousness, but one in which the dream images represent realities. If we study the dream as it is to-day, we shall find in its manifold images much that is chaotic, because our present dream consciousness is an ancient inheritance. But if we study the consciousness that preceded that of today, we should find that we could not at that time see external objects such as plants, for instance. Thus it was impossible for us to receive an external impression. Anything that approached us evoked an impression analogous to that of a dream, but corresponded to a certain external object or impression. Thus before dealing with the Ego-consciousness, we shall have to deal with a consciousness which might be termed an astral consciousness, because it is attached to the astral body which was formerly the most exalted member. It is dim and nebulous, and not yet irradiated by the light of the Ego. When man became earth-man, this consciousness was outshone by the Ego-consciousness. The astral body, however, is still within us, and we might ask how it was that our astral consciousness could be so dimmed and eliminated that the Ego-consciousness could fully take its place? This became possible because through man's impregnation by the Ego, the earlier connection between the astral body and the etheric body was greatly loosened. The earlier and more intimate connection was, so to speak, dissolved. Thus before the Ego-consciousness, there existed a far more intimate relationship between man's astral body and the lower members of his being. The astral body penetrated further into the other members than it does today. In a certain respect the astral body has been wrested from the etheric and physical bodies. We must make ourselves quite clear about this process of the partial exit, this detachment of the astral body from the etheric and physical bodies. Even today, might there not be a possibility with our ordinary state of consciousness to establish something similar to this ancient relationship? Could it not happen also today in a human life, that the astral body should try to penetrate further into the other members than it ought, to impregnate and penetrate more than is its due? A certain normal standard is necessary for the penetration of the astral body into the etheric and physical bodies. Let us suppose that this standard is exceeded in one direction or another. Certain disturbances in the whole of the human organism will result from this. For what man is to-day depends upon that exact relationship between the various principles of his being which we find in a normal waking state. As soon as the astral body acts wrongly, as soon as it penetrates deeper into the etheric and physical bodies, there will be disorder. In our past discussions we saw that this really takes place. We then looked at the whole process from another aspect. When does this happen? It happens when man in an earlier life impregnated his astral body with something, allowed something to flow into it that we conceive as a moral or intellectual transgression for that earlier life. This has been engraved on the astral body. Now, when man enters life anew, this may in fact cause the astral body to seek a different relationship with the physical and etheric bodies than it would have sought had it not in the preceding life been impregnated with this transgression. Thus are the transgressions committed under the influence of Ahriman and Lucifer transformed into organising forces which, in a new life induce the astral body to adopt a different relationship towards the physical and etheric bodies than would be the case had such forces not intervened. So we see how earlier thoughts, sensations, and feelings affect the astral body and induce it to bring about disorders in the human organism. What happens when such disorders are brought about? When the astral body penetrates further into the physical and etheric bodies than it normally should, it brings about something similar to what takes place when we awaken, when our Ego sinks down into the two lower principles. Awakening consists in the sinking down of the Ego-man into the physical and etheric bodies. In what then consists the action of the astral body when, induced by the effects of earlier experiences, it penetrates the physical and etheric bodies further than it should? That which takes place when our Ego and our astral body sink down into our physical and etheric bodies on awaking and perceive something, shows the very fact of our awakening. Just as the state of waking is the result of the descent of the Ego-man into our physical and etheric bodies, there must now take place something analogous to what is done by the Ego—something done by the astral body. It descends into the etheric body and the physical body. If we see a man whose astral body has a tendency towards a closer union with the etheric and the physical bodies than should normally take place, we shall see the astral body accomplish the phenomenon which we otherwise achieve by the Ego upon awakening. What is this excessive penetration of the physical and etheric bodies by the astral body? It consists in that which may otherwise be described as the essence of disease. When our astral body does what we otherwise do upon awakening, namely pushes its way into the physical body and the etheric body, when the astral body which normally should not develop any consciousness within us, strives after a consciousness within our physical and etheric bodies, trying to awaken within us, we become ill. Illness is an abnormal waking condition of our astral body. What is it we do when in normal health we live in an ordinary waking condition? We are awake in ordinary life. But so that we could possess an ordinary waking condition, we had at an earlier stage to bring our astral body into a different relationship. We had to put it to sleep. It is essential that our astral body should sleep during the day whilst we are dominated by our Ego-consciousness. We can be healthy only if our astral body is asleep within us. Now we can conceive of the essence of health and illness in the following way. Illness is an abnormal awakening within man of the astral body, and health is the normal sleeping state of the astral body. And what is this consciousness of the astral body? If illness really is the awakening of the astral body, something like a consciousness must be manifested. There is an abnormal awakening, and so we can expect an abnormal consciousness. A consciousness of some kind there must be. When we fall ill something must happen similar to what occurs when we awake in the morning. Our faculties must be diverted to something different. Our ordinary consciousness awakens in the morning. Does any consciousness arise when we become ill? Yes, there arises a consciousness that we know all too well. And which is this consciousness? A consciousness expresses itself in experiences! The consciousness which then arises is expressed in what we call pain, which we do not have during our waking condition when in ordinary health, because it is then that our astral body is asleep. ‘The sleeping’ of the astral body means that we are in regular normal relationship to the physical and etheric bodies, and are without pain. Pain tells us that the astral body is pressing into the physical body and the etheric body in such a way in an abnormal state, and is acquiring consciousness. Such is pain. We must not apply this statement without limits. When we speak in terms of Spiritual Science we must put limits to our statements. It has been stated that when our astral body awakens, there arises a consciousness that is steeped in pain. We must not conclude from this that pain and illness invariably go together. Without exception, every penetration into the etheric and physical bodies by the astral body constitutes illness, but the inverse does not hold. That illness may have a different character will be shown by the fact that not every illness is accompanied by pain. Most people take no notice of this because they usually do not strive after health, but are satisfied to be without pain; and when they are without pain they believe themselves to be healthy. This is not always the case; but generally in the absence of pain, people will believe themselves to be healthy. We should be under a great delusion if we believed that the experience of pain goes always together with illness. Our liver may be damaged through and through, and if the damage is not such that the abdominal wall is affected, there will be no pain at all. We may carry a process of disease within us which in no way manifests itself through pain. This may be so in many instances. Objectively regarded these illnesses are the more serious, for if we experience pain we set to work to rid ourselves of it, but when we have no pain we do not greatly trouble to get rid of the disease. What is the position in those cases where there is no pain with illness? We need but remember that only little by little did we develop into human beings such as we are today, and that it was during our earth period that we added the Ego to the astral body, etheric body, and physical body. Once, however, we were men who possessed only etheric body and physical body. A being possessing only these two principles is like a plant of the present day. We meet here a third degree of consciousness infinitely more vague, which does not attain to the clarity even of today's dream consciousness. It is quite a mistake to believe that we are devoid of consciousness when we sleep. We have a consciousness, but it is so vague that we cannot call it up within our Ego to the point of memory. Such a consciousness dwells also within plants; it is a kind of sleep consciousness of still lower degree than the astral consciousness. We have now reached a still lower consciousness of man. Let us suppose that through experiences in a previous incarnation we have brought about not only that disorder which comes into our organism when the astral body goes beyond its bounds, but also disorder caused by the etheric body pushing its way wrongly into the physical body. There certainly may arise such a condition where the relationship between the etheric body and the physical body is abnormal for present day man, where the etheric body has penetrated too far into the physical body. Let suppose that the astral body takes no part in this; but that the tendency created in an earlier life effects a closer connection that there should be between the etheric body and the physical body in the human organism. We have here the etheric body behaving in the same way as the astral body when we have pain. If the etheric body in its turn sinks too deeply down into the physical body, there will appear a consciousness similar to that which we have during sleep, like the plant consciousness. It is not surprising therefore that this is a condition of which we are not aware. Anyone unaware of sleep will be equally unaware of this condition. And yet it is a form of awakening! As our astral body will awake abnormally when it has sunk too deeply into the etheric and physical bodies, so will our etheric body awake in an abnormal manner when it penetrates too deeply into the physical body. But this will not be perceived by us, because it is an awakening to a consciousness even more vague than the consciousness of pain. Let us suppose that a person has really in an earlier life done something that between death and re-birth is so transformed that the etheric body itself awakens, that is, it takes intense possession of the physical body. If that happens there awakes within us a deep consciousness that cannot however be perceived in the same manner as other experiences of the human soul. Must it, however, be ineffectual because imperceptible? Let us try to explain the peculiar tendency acquired by a consciousness which lies still one degree deeper. If you burn yourself—which is an external experience—this causes pain. If a pain is to appear, the consciousness must have at least the degree of consciousness of the astral body. A pain must be in the astral body; thus, whenever pain arises in the human soul, we are dealing with an occurrence in the astral body. Now let us suppose something happens which is not connected with pain, but is, however, an external stimulus, an external impression. If something flies into your eye, this causes an external stimulus and the eye closes. Pain is not connected with it. What does the irritant produce? A movement. This is something similar to what occurs when the sole of your foot is touched; it is not pain, but still the foot twitches. Thus there are also impressions upon a human being which are not accompanied by pain, but which still give rise to some sort of an event, namely, a movement. In this case, because he cannot penetrate down into this deep degree of consciousness, the person does not know how it comes about that a movement follows the external stimulus. When you perceive pain and you thereby repulse something, it is the pain which makes you notice that which you then reject. But now something may come which urges you to an inner movement, to a reflex movement. In this case the consciousness does not descend to the degree at which the irritant is transformed into movement. Here you have a degree of consciousness which does not come into your astral experience, which is not experienced consciously, which runs its course in a kind of sleep consciousness, but is not, however, such, that it does not lead to occurrences. When this deeper penetration of the etheric body into the physical body comes about, it produces a consciousness which is not a pain consciousness, because the astral body takes no part in it, but is so vague that the person does not perceive it. This does not necessarily mean that a person in this consciousness cannot perform actions. He also performs other actions in which his consciousness takes no part. You need only remember the case in which the ordinary day-consciousness is extinguished and a person while walking in his sleep commits all kinds of acts. In this case there is a kind of consciousness which the person cannot share in, because he can only experience the two higher forms of consciousness: the astral consciousness as pleasure and pain, etc., and the Ego-consciousness as judgement and as the ordinary day-consciousness. This does not imply that a man cannot act under the impulse of this sleep consciousness. Now we have the consciousness which is so deep that a man cannot attain to it when the etheric body descends into the physical body. Let us suppose that he wishes to do something concerning which in normal life he can know nothing, which is connected in some way with his circumstances; he will do this without knowing anything about it. Something in him, namely, the thing itself, will do this without his knowing anything about it. Let us now take the case of a person who through certain occurrences in a former life has laid down causes for himself, which in the period between death and re-birth work down to where they lead to a penetration of the etheric body into the physical body. Actions will proceed from this which lead to the working out of more deeply-lying processes of disease. In this case the person will be forced by such activities to search out the external causes for these diseases. It may seem strange that this is not clear to the ordinary Ego-consciousness—but a person would never do it from this consciousness. He would never in his ordinary Ego-consciousness expose himself to a host of bacilli. But let us suppose that this dim consciousness finds that an external injury is necessary, so that the process which we have described as the whole purpose of illness may come about. This consciousness which penetrates into the physical body then seeks for the cause of the disease or of the illness. It is the real being of man which goes in quest of the cause for illness in order to bring about what we called yesterday the process of illness. Thus from the deeper nature of disease and illness we shall understand that even if no pain appears, inner reactions may always come, but if pain is manifested—as long as the etheric body penetrates too far into the physical body—there may always come that which one may call: the search for the external causes of illness through the deeper-lying strata of human consciousness itself. Grotesque as it may sound, it is nevertheless true, that we search with a different degree of consciousness for the external causes of our diseases—just as we do for our inherited characteristics—when we need them. But, again, what we have just said only holds good within the limits we have described to-day. In this lecture it has been our special task to show that a person may be in the position—without following it with the degree of consciousness of which he is aware—to look for an illness, and this is brought about by an abnormal, deeper condition of consciousness. We had to show that in an illness we are concerned with an awakening of stages of consciousness which as human beings we have long transcended. Through committing errors in a previous life, we have evoked deeper degrees of consciousness than are appropriate to our present life; and what we do from the impulses of this deeper consciousness influences the course of the disease, as well as the process which actually leads to it. Thus we see that in these abnormal conditions ancient stages of consciousness appear which man has long since passed. If you consider the facts of every-day life but a little, you will be able to understand in a general way what has been said today. It is indeed the case, that through his pain, man descends more deeply into his being, and this is expressed in the well-known statement that a person only knows that he possesses an organ when it begins to give him pain. That is a popular saying, but it is not so very stupid. Why does a person in his normal consciousness know nothing about it? Because in normal cases his consciousness sleeps so deeply that it does not dip intensely enough into his astral body; but if it does, then pain appears, and through the pain he knows that he has the organ in question. In many of the popular sayings there is something which is quite true, because they are heirlooms of earlier stages of consciousness in which man, when he was able to see into the spiritual world, was aware of much that we now have to acquire with effort. If you understand that a person may experience deeper layers of consciousness, you will also understand that not only external causes of illness may be sought by man, but also external strokes of fate which he cannot explain rationally, but the rationality of which works from the deeper strata of consciousness. Thus it is reasonable to suppose that a man would not out of his ordinary consciousness place himself where he may be struck by lightning; with his ordinary consciousness he would do anything to avoid standing where the lightning may strike him. But there may be a consciousness active within him, which lies much deeper than the ordinary consciousness, and which from a foresight which is not possessed by the ordinary consciousness leads him to the very place where the lightning may strike him—and wills that he should be so struck. The man really seeks out the accident. We have understood that it is possible to attribute karmic influences to accidents and other exterior causes of illness. How this is brought about in detail, how those forces which are in the deeper layers of consciousness act on human beings, and whether it is permissible for our ordinary consciousness to avoid such accidents, are questions we shall be dealing with later. In the same way as we can understand that if we go to a place where we may be exposed to an infection, we have done so under the influence of a degree of consciousness that has driven us there, so also must we be able to understand how it is that we take precautions to render such infections less effective, and that through our ordinary consciousness we are in a position to counteract these effects by hygienic measures. We must admit that it would be most unreasonable if it were possible for the sub consciousness to seek disease germs if they could not on the other hand be counteracted through the ordinary consciousness. We shall see that it is both reasonable to seek out causes of illness, and reasonable too, out of the ordinary consciousness to take hygienic measures against infection, thus hindering the causes of illness. |

| 108. Novalis

26 Oct 1908, Berlin Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| —The distances of memory, the wishes of youth, the dreams of childhood, the brief joys and vain hopes of a whole long life, arise in gray garments, like an evening vapor after the sunset. |

| On her neck I welcomed the new life with ecstatic tears. It was the first, the only dream—and just since then I have held fast an eternal, unchangeable faith in the heaven of the Night, and its Light, the Beloved. |

| Have courage, evening shades grow gray To those who love and grieve. A dream will dash our chains apart, And lay us in the Father's lap. |

| 108. Novalis

26 Oct 1908, Berlin Translated by Hanna von Maltitz Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Some poetry will be recited now and a corresponding mood in profound sense can only be created because the largest part of the friends present here have lately been deeply concerned with material concerning the spiritual world in relation to the entire historical development of humankind. What will be presented here in this lecture will bring to our awareness how spiritual science or Theosophy is not only something merely announced to the world through the Theosophical Society but that Theosophy as a teaching is based on the greater occult truth and wisdom which has already flowed through ancient times through the best minds searching for the Higher Worlds. We can find personalities in olden and recent times who can in actual fact show that in their imagination, ideas, feelings and experience, in their life mood they were totally permeated with a world view we could call theosophical and from which they worked, and that their entire life's activity unfolded in harmony with this. One such extraordinary personality lived in Novalis during the last three decades of the eighteenth century. Not even reaching thirty years of age was Novalis, and we hope that through the lecture of his “Hymns to the Night” an awareness will be able to develop, which speaks out of these Hymns—so complete, as it was only possible in the last three decades of the eighteenth century—in an all encompassing manner, the precise knowledge of these spiritual scientific truths. Out of a highly respected aristocratic family, Friedrich von Hardenberg, called Novalis, was born on 2 May 1772. Whoever has the opportunity to visit Weimar must not hesitate to view the impressive Novalis bust. It belongs to the classic records of Weimar, and clearly expresses how closely the spiritual high culture was connected to this time, the end of the eighteenth century. Whoever views this extraordinary bust will, if he or she has any sensitivity for it, get the impression that, one could say, out of this sphere of humble humanity the physiognomy of his soul expresses that he was totally established in the occult, in the spiritual worlds. To add to this, Novalis is one of those personalities who is a living proof of the possibility to connect this spirituality, this self-elevation in the highest sense of human beings reaching the spiritual worlds, to connect this to a solid practical `standing on the ground' physical reality. Basically Novalis never entered an angry conflict with the still conservative traditions in which his family circle lived, but we can take into consideration, that this family always had an open receptivity for everything noble and good, also when coming into contact with unknown people. When we study Novalis' biography—it is in itself a work of art—and we allow it to work on us, his father is shown as having a practical, applied nature. Novalis was actually in his civil life educated for a totally practical career, for which knowledge of law and mathematics was necessary. He became a mountain engineer. Here is not the place to explore how he actually became a delight in this career for those whom he worked. It is also not the moment now to show how the mathematical-materialistic sciences, which lay at the foundation of this career, not only in full theory and practice came to be controlled by him completely, but that he was a diligent mathematician. What is most important is that Novalis as a spiritual being allowed mathematics to penetrate into his inner development. When mathematics showed him how it is suitable for the elevation of pure sense-free thought, then we have where relevant, to refer to a classic example as here with Novalis, where outer observation doesn't have a say. For him life in the mathematical imagination became a great poem which filled him with delights, allowing his soul to experience an elevation when he dived into numbers and sizes. For him mathematics became the expression of divine creation, divine thought as it flashes through space in powerful directions and in measures of power and crystallize out there. Mathematics became for his mindset the warmest way to the spiritual life, while for many people, who only know mathematics from outside, it remains cold. It is so much more meaningful that we meet this spirituality in Novalis in a gentleness and refinement, as we would not meet in one or other of the most important intellects. Novalis was a contemporary of Goethe. One should not place the kind of spirituality within Novalis, on the same level as what Goethe had. Goethe came to it through a regulated, out of a Higher World directed course towards an initiation, up to a particular stage. Novalis, by contrast, lived a life which one can best describe by saying: This young man, who left the physical plane at the age of twenty nine and who gave the German intellectuals more than a hundred thousand others could give, he lived a life which was actually a memory of a previous one. Through a quite specific event the spiritual experiences of earlier incarnations appeared, presented themselves to his soul and flowed in gentle, rhythmically woven poems from his soul. Thus we can see that Novalis understood how the human being's soul can be lifted up into a higher world. For Novalis it gave the possibility to see that waking everyday awareness is only a fragment in a current human life, and how the soul who in the evening leaves the daily awareness and sinks into unconsciousness, in actual fact sinks into the spiritual world. He was able to experience deeply and to know, that in these spiritual worlds which are entered by the soul at night, lived a higher spiritual reality, that the day with all its impressions, even the impression of sun and light, only formed a fragment of the entire spiritual worlds. The stars, surreptitiously sending away the light of day during the night, appeared to him only in a weak glow, while in him spiritual truths rose up in his consciousness, which for the clairvoyant appears illuminated in a dazzling bright astral light when during the night he shifts himself spiritually into this state. During the night the actual spiritual worlds appeared to Novalis and thus the night from this perspective became valuable. What enabled his memories of an earlier incarnation to appear? How did it happen that the experiences of the occult world, which we can reveal today in occult knowledge, rose so uniquely in him? His life unloosened him from the soul in whose knowledge slumbered earlier incarnations. One must take the result, which these spiritual experiences lifted out of this soul, back into the light of a spiritual observation, if one wants to understand it. Only childlike folly could place these experiences on the same footing as Goethe's meeting and Friederikes zu Sesenheim. This would be a coarsely unrefined comparison. During his stay in Grüningen he became acquainted with a thirteen year old girl. Soul secrets played here which one could never, without abandoning the gentleness of a soul, call this a love relationship. Basically there was in Sophie von Kühn—that was her name—something like the lives of various beings. She became ill and soon died. The moment her spirit loosened from Sophie von Kühn, it wrestled with Novalis' inner life, awakening inner spiritual abilities. Perhaps you could, when you allow yourself to admit it, obviously see the inability of a way of thought bound by outer experience coming to the fore here in what we must experience in judging these relationships, which can only be understood if we want to understand it in its spirituality, in our present materialistic time. People say science must be based on documentation; it must absolutely lead from everything concrete on the physical plane. Such natural scientists, who surely present a distorted side, the farcical side of natural science, have allowed us to experience what they believe in, that by presenting documents, Novalis basically had fallen prey to an illusion. The poetry is nice—they say—but show us the documents, let us look at who Herr von Rockenthien was where Sophie von Kühn lived. Look at—so the “Novalis adherents” said—various letters Sophie von Kühn wrote to Novalis. Sopie von Kühn made not only in every line but nearly in every word, a writing or spelling error! - concluding Novalis had fallen victim to a big deception. In Jena, where she spent the last years, she also encountered Goethe—and made a deep impression on Goethe! Whoever can't comprehend that these unique words of Goethe are more valuable than documents which can be dug up—because all documents can lie—whoever wants to come with proof to show something, will not consider producing counter evidence, it will not help him, despite all his science. What was the result for Novalis? Sophie von Kühn passed away and Novalis lived within a mood of: “I will emulate her in death” (Ich sterbe ihr nach!). Nevermore was he separated from her soul. Pouring out of the deceased soul of Sophie von Kühn came a force which he had in his own soul experienced as a mediator in the night, and within him rose enormous experiences which he depicted in his poetry. Once again another feminine individual crossed his path: Julie von Charpentier. To him however, she was only the earthly symbol of Sophie von Kühn's deceased soul. Dissolved out of his soul were the elements of wisdom which he poured into the “Hymns to the Night”, through this first soul bond. (Marie von Sivers (Marie Steiner) read the first two Hymns at this point.) So far does this poem transport us into the worlds in which Novalis lived as a spirit, when he experienced from within the everlasting elements of wisdom. You might often have heard that such reaching into the higher worlds is linked to a penetration of other secrets of existence. Out of this, a backward glance into the prehistoric times is necessary, where that, which now lives in the world, only existed as a sprig in the Divine and had not yet come down into an earthly form. When the soul of the natural kingdoms still existed in pure spirit, only perceptible in the astral world, all this contributed to the impressive images unfolding to Novalis the seer, when he glanced back. He saw the time when the souls of plants, animals and people were still companions of divine beings, when an interruption in awareness had not yet happened as it did later to human beings in the exchange between night and day—while nothing was influenced by any interruption, as is expressed in the words: birth and death. Everything living flowed in the spiritual-soul where there was no sense of death in this prehistoric past. Then the thought of death struck into the life of these gods and divine earthly beings, and down into the earthly world the spirits moved. The godly beings were concealed in earthly bodies, the godly beings were enchanted into the mineral, plant and animal realms. Those who were able to return to the spiritual worlds found the gods within all phenomena, they recognised the earlier gods as linked to the human beings before an earthly existence began. They learnt what the life of a soul was, learnt to recognise that the day with its impressions creates a weaker fragment out of the great world of the beings whose existence was endurance, eternity. They learnt to become disenchanted by the world of nature. This happened to Novalis' soul when he united his eternity to Sophie's soul by emulating her in death. In this emulation his spirit flourished. He experienced “die to live” and in him rose what he called his “magical idealism”. (Now followed the recitation of the fourth hymn, from part 20, and the start of Hymn 5.) In this way Novalis could glance back to a time in which gods moved among men, when everything took place spiritually because spirits and souls had not yet descended into earthly bodies. He perceived a point of transition: how death hit the world and how the human beings during this time placed death as their earthly shadowing and how he tried to brighten it up through fantasy and art. But death remained a riddle. Then something of universal significance happened. Novalis could perceive the universal meaning of what had happened at that time on earth. Souls from the kingdoms of nature descended to the earth. Forgotten were the memories of their spiritual original existence, yet a unique spiritual Being remained in this universal womb of creation from which everything descended. One Being provisionally held back; it had held itself above and only provisionally sent its gift of grace downward, and then, when human beings needed it the most, it also descend into the earthly sphere. It remained in the spiritual spheres above the being of the spiritual light, this Being was hidden behind the physical sun. It held itself in heavenly spheres and descended when human beings needed to once again be able to rise up to spiritual worlds. It descended with the Mystery of Golgotha when Christ appeared in a physical body. Humanity understands Christ in His universal unfolding when the life of Jesus of Nazareth is followed back to His spiritual origins, to the unsolvable riddle of death. The Greek spirit of death appears as a pondering muse, as an enigma which cannot be solved. Even the Greeks sensed that the riddle which is hidden in the youth's soul, found its solution with the Event of Golgotha, that here victory overcomes death and as a result a new impulse is given to humanity. This Novalis could see and as a result there appeared to him, from the mystery of faith and the mystery wisdom, the Star which the old Magi had followed. As a result he understood the actual essence of what the Christ death implied. In the night of the soul the riddle of death revealed itself to him, the riddle of the Christ. This was it, which this extraordinary individual wanted to learn—through the memory of earlier lives—what the Christ, what the event of Golgotha signified for the world. In closing Marie von Sivers (Marie Steiner) recited the ending of the fifth and the sixth Hymn.Hymns to the Night |

| 270. Esoteric Lessons for the First Class I: Fifth Hour

14 Mar 1924, Dornach Translated by Frank Thomas Smith Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| One would like to say: divinity is hidden within nature. It only appears to lack divinity. At most in dreams do we see a relationship between nature and the inner life of man. We can become aware of how an irregularity in our breathing process in one direction or the other can cause happy dreams or fearful and anxiety-filled ones. We can be aware of how the purely natural overheating of a room can give a kind of moral content to certain dreams. Dreams pull nature into the psyche. However, we also know that in dreams our consciousness is submerged, and dreams are not what can directly describe the spiritual to us. |

| That man lives and moves in the element of air is obvious from a completely exterior point of view. One needs only to look at dreams to see how dependent they are on irregularities, abnormalities in the breathing process. When the breathing process takes place while awake, we don't notice it, because in general we pay little attention to normal life processes. |

| 270. Esoteric Lessons for the First Class I: Fifth Hour

14 Mar 1924, Dornach Translated by Frank Thomas Smith Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

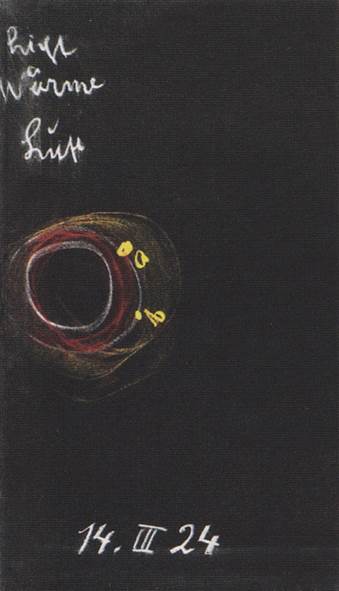

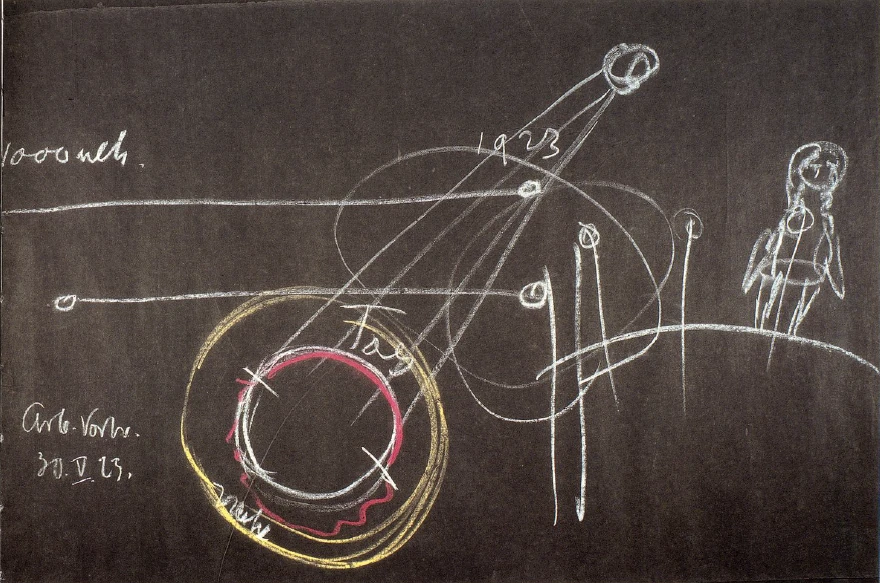

My dear friends, We have seen the changes which take place in a person who encounters the Guardian of the Threshold. And whether he or she is able to approach and come to an understanding of the spiritual world in any form, depends upon understanding the essence of this Guardian. In particular, we have seen how what constitutes man's inner self - thinking, feeling, willing - undergoes a substantial transformation in the Guardian of the Threshold's domain. Especially in the last lesson here, it became clear to us how in a certain respect thinking, feeling and willing go different ways upon entering the spiritual world, how they enter into different relationships than those which usually prevail for earthly consciousness. We have seen how through his will man is greatly influenced by earthly conditions. At the moment when the person approaches the spiritual world, in a certain sense thinking, feeling and willing become separated. The will, now living much more independently than previously in the soul, shows itself to be much more related to the forces which attract man to the earth. Feeling shows itself to be related to the forces which hold man in the periphery of the earth through which the light penetrates when it shines upon the earth in the morning, and which disappears from sight on the opposite side in the evening. Thinking, however, is the force which relates upwards to the heavenly. So that in the moment that man stands before the Guardian of the Threshold, this Guardian draws his attention to how he belongs to the whole world: through his will the earth, through his feeling the periphery, through his thinking the higher powers. But that, my dear friends, is exactly what must be made clear - that upon entering the spiritual world a growing together with the universe occurs. For normal consciousness we stand here in the world while outside of us are the forces which are active in the plant, mineral, animal kingdoms, to which we have access through our senses, but which at first indicate no relationship to human beings. So here we stand, apart, looking inwards at our thinking, feeling and willing, aware that our thinking, feeling and willing are somewhat separated, apart from external nature. And we feel a deep chasm between our human nature and the expansive nature around us. But this chasm must be bridged. For this chasm, only the exterior aspects of which are perceived by normal consciousness, is the threshold itself. And our being able to perceive the threshold depends on our ceasing to simply accept this unconsciousness, when we look within ourselves, concerning an external nature which we perceive as being foreign to humanity. For this chasm needs to be understood as being not only extremely important for human life, but also for the entire universe. Well, you see, at the moment when one enters the esoteric, a bridge over this must be built. We must, in a sense, merge with nature. We must stop saying to ourselves: Out there is nature, which has nothing to do with morality. We don't ask the minerals about morality, although it is of prime interest to us, nor do we ask the plants, or the animals - and in this materialistic age we have even ceased asking humans, because only human physicality is taken into consideration. And also when looking into the inner human we see what for normal consciousness is passive thinking, with which we can indeed visualize the world pictorially, but which is nevertheless powerless. Our thoughts are at first things we own which allow us to recognize the objects in the world. As thoughts they have no power. Our feeling is our inner life. To a certain extent we are separated through it from the world. Our will does communicate external objects to us, but in so doing the external objects take on something foreign to their nature. Something truly great happens to a person when he becomes aware of the abyss which exists between himself and nature: something great. Something which has been expressed since ancient times with these words, words which must be understood anew in every age: Nature must appear as divine, and the human must be a magical being. What does it mean, that nature must be able to appear as divine? Nature must be able to appear as divine. The way it appears to the senses, and how reason understands it, it is certainly not divine. One would like to say: divinity is hidden within nature. It only appears to lack divinity. At most in dreams do we see a relationship between nature and the inner life of man. We can become aware of how an irregularity in our breathing process in one direction or the other can cause happy dreams or fearful and anxiety-filled ones. We can be aware of how the purely natural overheating of a room can give a kind of moral content to certain dreams. Dreams pull nature into the psyche. However, we also know that in dreams our consciousness is submerged, and dreams are not what can directly describe the spiritual to us. Rather than the sleeping consciousness, we must see how the awakened consciousness presents nature. Now in nature, my dear friends, we have a relationship of the human physical body with what is solid, with what is characteristic of the earthly element. We have a relationship of the human etheric body with what is characteristic of water. However, this relationship of the human physical body with the earthly, and the relationship of the human etheric body with the liquid element lie deep beneath what people experience. What is closer to man is his breathing process, which is dependent upon the air. So it is from the breathing process upwards where the region begins where man can feel himself- when he is approaching the spiritual - related to nature. The breathing process contains the air element, in which we exist. air Above the element of air we have the quality of warmth. warmth And above the element of warmth we have the essence of light: warmth-ether, light-ether. light When we go even higher we come to a region - which we will speak about later - which does not lie so close to humans. That man lives and moves in the element of air is obvious from a completely exterior point of view. One needs only to look at dreams to see how dependent they are on irregularities, abnormalities in the breathing process. When the breathing process takes place while awake, we don't notice it, because in general we pay little attention to normal life processes. That the element of warmth is extremely essential to man is obvious to even superficial observation. If we dab our skin with an object that is colder than our body, a cold knitting needle for example, we feel the cold places that have been touched as separate even though they are very close to each other. We are very sensitive to the cold. If we touch our skin with an object that is warmer than our body, we don't feel the difference so clearly. We can hold two cold knitting needles very close to each other and feel the coldness of both. If we hold two warmed needles, the close contacts flow together at one point, and we must hold them quite far apart in order to sense them as separate. In fact we are far more sensitive to cold than to warmth. Why? We endure warmth much better then cold because we are creatures of warmth, because warmth is our own nature and we live and act in it. Cold is foreign to us and we are very sensitive to it. It is more difficult for normal consciousness to understand light. Today we want to approach these things esoterically. So it may be sufficient that I have indicated what air and warmth means to normal consciousness. But with this consciousness man feels air as something external, natural. He also feels warmth as something that touches him from without, and he also feels that light comes to him from outside himself. In the moment when a person takes the leap in his life which brings him near to the Guardian of the Threshold, he becomes aware of how intimately he is related to what otherwise seems alien to him. I have often pointed out how in every moment of our lives, also for normal consciousness, we can become aware of our relationship to the universe through our relation to the air. The air is outside, the same air which is inside me a moment later, then it is again outside, the same air which was within me. But we are not aware of the fact that, in the sense that we are beings of air, that what we hold within us we let out again, then take what was external into us again, so that we become one with the whole life and being of the element of air in which we exist as earthly beings. Whereas we always carry our muscles and bones within us, so we are only conscious of their origination and passing away during the embryonic and dying stages. At the moment we enter the spiritual region this is no longer the case. We then feel how with every exhalation we fly out on the wings of the exhaled air into the expanse of being into which the exhaled air disperses. And how by inhaling we take into us the spiritual beings who live in the circulating air. The spiritual world flows into us when inhaling; our own being flows out into the environment upon exhaling. This is not only so in respect to the air, but to an even greater degree in respect to warmth. As we are one with the air environment which encircles the earth, so are we also one with the warmth which encircles and penetrates the earth. [Two white circles are drawn: air, then a red one: warmth.]

When we approach the spiritual world we truly experience the spirit entering us when inhaling, our own being streaming out into the expanse of space when exhaling, that is, we experience a spiritual interweaving of inhaling and exhaling. And we feel more intensively how with the increase of warmth - in that we are ourselves within the element of warmth - we become more human, and with the lessening of warmth we become less human. Thus warmth ceases to be a merely natural element, for we feel and recognize the spiritual nature of warmth - and we feel it to be closely related to our being human. We feel that the increase of warmth means that the spirits which are active in the element of warmth say: We give you your humanity through the element of warmth; we take it away through the element of cold. So we come to the light, in which we live and act. But we don't notice it because with normal consciousness we have no idea of the fact that the inner movements of light are contained in our own thinking, that every thought is captured light - both for the physically sighted and for the physically unsighted. Light is objective. Not only the physically sighted receive it, the physically unsighted also receive it ... when they think. Because the thoughts which we hold within us, which we capture, is light present within us. We can say then, that when we approach the Guardian of the Threshold he admonishes us in the following way: When you think, O man, your being is not in you, it is in the light. When you feel, your being is not in you, it is in the warmth. When you will, your being is not in you, it is in the air. Keep not within yourself, O man. Think not that your thinking is in your head. Think that your willing is none other than the moving, living, active air element working within. One must be very conscious of the fact that in the Guardian of the Threshold's presence one is divided into the universal elements, that one can no longer simply hold one's self together in the usual chaotic, dim way of normal consciousness. And that is the grand experience that initiate knowledge gives to the human being, that he ceases to seriously think that he is enclosed within his skin - something which is no more than a mere indication that he exists. For spiritual consciousness what is concentrated within the skin is an illusion; for man is as great as the universe. His thoughts are as wide as the light, his feelings are as wide as the warmth, his will is as wide as the air. If a being of sufficiently developed consciousness were to descend to the earth from another planet, he would speak to people in quite a different way than how people of the earth address each other. He would say: The light which envelops the earth is differentiated [The cloak of light is drawn around the air and warmth circles: yellow.] Many individually differentiated beings are in the light. One must imagine that in this earth-light, in the light that surrounds the earth, that weaves and waves around it, in this space many beings are present, as many as there are human beings on the earth. They all accommodate themselves within the earth's world of light. And for this visitor from space all human thoughts are in this cloak of light. And all feelings are in the cloak of warmth, and all willing is in the atmosphere, in the cloak of air. Then this being would say: I have qualitatively differentiated out a being. It is indicated by body a; another, also within the cloak, is designated as b, and so on [within the yellow, two spots, a and b, are drawn]. The real human beings are all together in the light, warmth and air surrounding the earth. For the person who really stands before the Guardian of the Threshold this is not speculation, but experience. And this is what constitutes spiritual progress, that man integrates with the surrounding world. It is of little use to speak of these things theoretically. It is not particularly profound mystically to say that you are one with the world by merely thinking that you are, if you do not begin to experience the fact that when you are thinking you are living in the entire earth's light, are becoming one with the earth's light, and how by doing so, by becoming one with the light of the earth, you go out of yourself - go out, so to speak, through all the pores of your skin into a divine-spiritual being - you become one with the essence of the earth itself and with the other elements of the earth's being. This is something which must be understood in all seriousness by anyone who strives toward relationship with the spiritual world. You see, light must, in a sense, have a moral effect. And we must be aware of how we are related to the light and how the light is related to us in the esoteric experience of the world. But then, at the moment when one steps over the threshold, it becomes clear that the light is real and must wage a hard battle with the forces of darkness. Light and darkness become real. And then something occurs to the person which makes him say to himself: If in my thinking I merge completely with the light, I will lose myself in the light. For in the moment when I merge with the light in my thinking, light-beings grasp hold of me and say: You, human, we will not let you out of the light again, we will hold you back in the light. This expresses the light-beings' will. They want to draw man to them through his thinking, make him one with the light, rend him from all the earthly forces and integrate him into the light. The light-beings who are around us are those who at every moment of existence wish to rend human beings from the earth and integrate them with the sunlight which flows over the earth. They live in the periphery of the earth and say: You, human being, should not remain with your soul in your body; with the sun's first light of dawn you yourself should shine down on the earth, you should set with the sun's afterglow, and encircle the earth as light! These light-beings will be found enticing us ever and again. At the moment of crossing the threshold one becomes aware of these light-beings who want to pull human beings away from the earth and try to convince him that it is not worthy of him to stay chained to the earth by its gravity. They wish to absorb him in the sun's radiance. Yes, for ordinary consciousness the sun is shining above and we humans stand below and let the sun shine on us; for the more developed consciousness the sun in heaven is the great tempter who wants to unite us with its light and pull us away from the earth - who whispers in our ear: O man, you don't need to stay on the earth, you can exist in the rays of the sun, then you can illuminate the earth and bring it happiness, so you no longer have to be illuminated and made happy on the earth from without. This is what we encounter when we meet the Guardian of the Threshold: nature, which was previously quietly outside us and made no claim on our normal consciousness, now has the force to speak to us morally. Nature appears in the sun as a tempter. What before was quietly shining sunlight now speaks enticingly, temptingly. And we first realize that there is something spiritual living and moving in this sunlight when the enticing, the tempting beings appear in the light of the sun who want to pull us away from the earth. For these beings are in continuous battle with what constitutes the interior of the earth - darkness. And if we fall into extremes - which is quite possible because the experiences in meeting the Guardian of the Threshold are most earnest and profound and gripping for the human soul - when we realize how enticing the sunlight is, caused by the light-beings, that is when we want to escape from them, if we remember that we are supposed to be human beings. We may not forget this. If we do, although we continue to live physically on the earth, we are to a certain extent psychically crippled. But when we become aware of how enticing the sunlight is, we turn to the opposite side and seek relief in darkness, against which the light is continually fighting. And by swinging from light to darkness we fall into the opposite extreme. So this self, which wanted to surge out into the bright shining sunlight, is now threatened in darkness by loneliness, by being separated from all other beings. But we human beings can only live in the area of equilibrium between light and darkness. Such is the great experience before the Guardian of the Threshold: that we face the enticement of light and the dehumanizing force of darkness. Light and darkness become moral forces which have moral power over us. And we humans must realize that it is dangerous to look at the pure light and the pure darkness. And we are reassured when, there at the threshold, we see how the middle gods, the good gods of normal progress dim the light to a luminous yellow, to a luminous red, and when we know that we can no longer be lost to the earth, when we are aware not of the light which enticingly dazzles us, but of the color in spirit, which is subdued light. And it is equally dangerous to yield to pure darkness. And we will be inwardly liberated if we do not stand before the pure darkness in spirit-land, but when we stand before the illuminated darkness as violet and blue. Yellow and red say to us in spirit-land: Light's enticements will not be able to wrest you away from the earth. Violet and blue say to us: The darkness will not be able to bury you, as soul, in the earth; you will be able to hold yourself above the effects of the earth's gravity. Those are the experiences where the natural and the moral grow together in one, where light and darkness become realities. And without light and darkness becoming realities, we will not be aware of the true nature of thinking. Therefore we should listen to the words the Guardian of the Threshold speaks when we meet him with our thinking, which has become independent and separated in our soul:

This means becoming aware of the duality in which one is placed and between which one must find equilibrium, harmony, in thinking. [The lines are written on the blackboard:]

The impulses which can derive from such words must be forcefully received by thinking and one must learn to feel when dealing even with normal exterior light, and exterior darkness, how this light can only be tolerated when it is dimmed to color. Then we must do our best to understand, with spiritual visioning, how thinking is placed in the middle of this battle between light and darkness: How, when it comes into contact with light, it is absorbed in a certain sense, interwoven with the light; and when it comes into contact with darkness it is extinguished. If we want to enter into matter, into dark matter, our thinking is extinguished. By understanding this, one gradually enters the spiritual realm. And, my dear friends, in order to experience this, one must have courage, inner courage. To deny that one needs courage is to be ignorant of the true situation. We may think that courage is needed to let a finger be cut off, but none is needed to allow the severed thinking to stream into the vortex in which it will be seized when it finds itself in the middle of the battle between light and darkness. And it is always there. Knowledge means that we are aware of this. In every waking moment, with his thinking, man is in danger because there are certain spiritual beings on neighboring heavenly bodies who know that in every century, in every age, it is possible, as far as humanity is concerned, for light to win over darkness or darkness to win over light. Yes, my dear friends, for people with normal consciousness life seems as little dangerous as it does for a sleepwalker who has not yet been woken up: he doesn't fall down. For someone who observes life, however, a battle ensues, and he cannot say with certainty whether in a hundred years light or darkness will have won, and whether the human race will even have an existence worthy of humanity. And he will know why such a catastrophe has not happened to human evolution until now. I could use another comparison. When you watch a tightrope walker on his rope you know that he could fall at any moment to the left or to the right. That you could be on such a tightrope psychically - that anyone can plummet psychically to the right or the left - there is no awareness of that in ordinary life, because one does not see the abyss on the left or right. Nevertheless, it is there. That is the benefit the Guardian of the Threshold bestows on man - that he does not let the abyss be seen until his own warnings alert him to it. That has been the secret of the Mysteries of all times, that the abyss is shown to the adept and he therewith is able to acquire the strength necessary for knowledge of the real world. As it is with light in regard to thinking, so it is with warmth in regard to feeling. When approaching to Guardian of the Threshold, one is aware of entering a battle between warm and cold: how warmth is always enticing our feeling, for it wishes to suck it in to itself. Just as the light-beings, the Luciferic light-beings would in a certain sense fly away with us from the earth towards the light, so would the Luciferic warmth-beings suck our feeling into the general universal warmth. All human feeling should be lost to humanity and soaked up into the general universal warmth. And this is enticing because what the initiate-science adept is aware of when he approaches the threshold with his feeling: the warmth-beings appear, who want to give the human being an over-abundance of his own element, of the element in which he lives: warmth. They want all his feelings to be soaked up by warmth. When the human being is aware of this however: when he approaches the threshold, the warmth-beings are there, he gets warm, warm, warm, he becomes warmth, he flows over into the warmth. It is a feeling of pleasure, and a great enticement. It flows through him continuously. One must know all this. For without knowing that this enticement exists within the desire for warmth, it impossible to obtain an unobstructed vision of spirit-land. And the enemies of these Luciferic warmth-beings are the Ahrimanic coldness-beings. These beings attract those who are still aware of how dangerous it is to bask in the pleasure of warmth. They would like to dip into the healthy cold. That is the opposite extreme: the cold can harden them there. And then, when the cold affects man in this way, infinite pain ensures, which is also physical pain. The physical and the mental, matter and spirit, become one. The human being experiences the cold capturing his whole being, as though tearing him apart in great pain. That the human being is continually engaged in this battle between warmth and cold is what one must understand as the Guardian of the Threshold's admonition in respect to feeling. [The second verse is written on the blackboard.]