| 124. Excursus on the Gospel According to St. Mark: Lecture One

07 Nov 1910, Berlin Translator Unknown |

|---|

| The driest, most desiccated ideas of the old philosophy are those of Kant and everything associated with Kantism. Kant's philosophy puts the main question in such a way that he cuts every link between what man evolves as ideas, between perceptions as an inner life, and that which ideas really are. |

| 124. Excursus on the Gospel According to St. Mark: Lecture One

07 Nov 1910, Berlin Translator Unknown |

|---|

We have often spoken of that period of human evolution that has passed since the Atlantean catastrophe. We have dealt with the various epochs of this evolution—the original Indian, original Persian, Egypto-Chaldean and Greco-Latin—and then with our own, the fifth epoch of post-Atlantean civilisation. We have also shown that two further epochs will pass, before the coming of another great catastrophe, so that we have to reckon in all seven such epochs of earthly humanity. It is comprehensible that these epochs should be described differently. For as men of the present day we desire to find how we stand as regards our own mission, we can only gain some idea of what lies before us in the future when we know how far we have participated in these different epochs in the past. I have often explained how we can distinguish between the separate human being, the little world, or microcosm, and the great world, or macrocosm; I have shown how man, the little cosmos, is a copy of the great world or macrocosm. Though this is a truth, yet it is a very abstract truth, and as generally stated does not mean very much. You will therefore find it helpful if we go into particulars regarding this, and show how certain things met with in mankind have really to be accepted as a little world, and can be compared with another, a greater world. The man of the present day really belongs to all seven ages of the post-Atlantean epoch. We have passed through all the earlier ages in former incarnations, and will pass through all the later ages in later ones. In each incarnation we receive what the age in question has to give. Because we receive this we bear within us, in a certain sense, the fruits of former evolutions, and the most intimate things within us are really those we have acquired during the ages mentioned. What each of us has acquired in the course of these ages is more or less within human consciousness to-day; while what we acquired generally in our Atlantean incarnations, when the state of consciousness was very different, has sunk more or less into our sub-consciousness, and no longer reverberates within us as that does which we have acquired in post-Atlantean times. In Atlantean times man was more shielded from having his evolution injured in one way or another, because his consciousness was not then so awake as it was in post-Atlantean times. For this reason all we bear within us as the fruits of our Atlantean evolution is more in accordance with the ordering of the world than is that which had its origin in an age when we were already capable of bringing certain things in us into disorder. Ahrimanic and Luciferic Beings certainly influenced man in Atlantean times, but they then worked quite differently, for man was not then capable of shielding himself from them. That men grew ever more and more conscious is the most important fact of post-Atlantean culture. In this respect human evolution from the Atlantean catastrophe until the next great catastrophe is macrocosmic. Humanity evolves like one great man throughout the seven post-Atlantean periods; and the most important things that were to arise in human consciousness during these seven periods resemble what a single individual experiences in the seven periods of his individual life. The different ages in the life of a man have been described as follows:—The first seven years, from birth to the change of teeth, is described as the first age. In it man's physical body receives its form, is endowed with it as a gift. With the coming of the second teeth this form, in all its essentials, is fixed. The man then continues to grow within this form, which has received its essential direction. What is accomplished during the first seven years is the construction of the form. This period has to be understood from all sides. We must, for instance, distinguish the first teeth which the child develops early and which fall out, from the second teeth which replace them. These two kinds of teeth, with respect to the laws of the body, are quite different—the first are inherited, they appear as the fruits of the organisms of the man's ancestors, but the second teeth appear as the outcome of the laws of the man's own physical Being! This has to be realised. It is only when we go into such particulars that we observe this difference. We receive our first teeth, because our ancestors pass them on to us with our organism, we acquire our second teeth because our own physical organism is so constituted that we acquire them through it. In the first period the teeth are directly bequeathed, in the second the physical organism is bequeathed, and it produces the second teeth. After this we distinguish a second period of life, that from the change of teeth until puberty, to about the 14th or 15th year. What is significant in it is the development of the etheric body. The third period, to about the 21st year, represents the development of the astral body. Then follows the development of the ego, and this progresses from the development of the sentient soul to that of the rational soul and on to the consciousness soul. It is thus we distinguish the different ages in the life of a man. In this life, as you know well, only that period is really ordered and regulated, which falls within the first seven years. This is, and must be so, as regards the man of the present day. Such regular differentiations as we find in the first three periods of a man's life do not occur later; neither is the time they last so clearly defined. If we enquire into the causes of this we have to understand that in the evolution of the world a middle period always comes after the first three of any seven periods. We are living at present in the post-Atlantean age, we have already within us the fruits of the first three periods, and of the fourth, for we are now in the fifth post-Atlantean age, and are living on towards the sixth. We are entirely justified in finding a resemblance between the evolution of the various post-Atlantean periods and that of the ages in the life of separate individuals, so that here also it is possible to distinguish between what is macrocosmic and what is microcosmic. Let us take that which is most characteristic of the first post-Atlantean period, the one we call the Old-Indian; for in this the character of the post-Atlantean evolution was most strongly expressed. In this first period an exalted and most clearly differentiated wisdom existed, a primeval wisdom. What was taught in India by the Seven Holy Rischis was in principle the same as was actually beheld in the spiritual world by natural seers, and also by a large part of the people at that time. This ancient wisdom was present in the first Indian period as an inheritance. It was experienced clairvoyantly in Atlantean times, but now it had become more of an inherited primeval wisdom, preserved and given out again by those who, like the Rischis, had risen to spiritual worlds by initiation. What had entered thus into human consciousness was essentially and absolutely an inheritance. It was therefore entirely different in character from present day wisdom. People make a great mistake when they try to express the important matters given out by the Holy Rischis in the first post-Atlantean period in forms similar to those employed by the science of to-day. This is hardly possible. The scientific forms in use to-day appeared first in the course of post-Atlantean culture. The knowledge of the Ancient Rischis was of a very different kind. Those who communicated it, felt how it worked in them, how it rose within them on the instant. If we are to understand what knowledge was at that time, we must realise that its most marked characteristic was that it did not spring in any way from memory. Memory played no part as yet in knowledge. I pray you to keep this in mind. To-day memory plays a main part in the passing on of knowledge. When a university professor mounts the platform, or a public speaker addresses an audience, he must be careful to consider beforehand what he is to speak about, and retain it in his memory. Certainly, there are people who say they do not require to do this, they follow their genius; but this does not take them very far. At the present day the passing on of knowledge depends really very largely on memory. We gain a correct perception of how knowledge was communicated in the ancient Indian epoch if we grant that knowledge first rose in the head of him who communicated it at the moment he passed it on to others. In former times knowledge was not prepared before-hand as it is to-day. The Rischis did not prepare what they had to say, so that their memory might retain it. They prepared themselves by attuning themselves to what they were about to communicate. They said:—“This knowledge (Wissen) is not built on memory in any way. Memory has no part in it, my soul must first enter into a holy atmosphere, it must be attuned to piety!” They prepared this atmosphere, this feeling, but not what they were to say. At the moment of communication it resembled rather a reading aloud from an invisible script. Listeners who took down in writing what was said would have been unthinkable at that time. This would have been an impossibility, anything preserved by such means would have been regarded at that time as worthless. Only those things were considered of value which a man preserved within his soul, and which his soul then moved him to reproduce and impart to others in the same way as he had received them. It would have been regarded as desecration to write down these communications. Why? Because in the opinion of that day it was thought that what was written on paper could not be the same as what was communicated by word of mouth. This tradition endured for a long time, for such things are retained far longer in the feelings than in the understanding of men, and when in the middle ages the art of printing was added to that of writing many people regarded it for long as a black art. The old feeling survived, that what passed in a living way from one soul to another should not be preserved in such a grotesquely profane way as was the case when black printer's ink traced spoken words on a white page, thus changing them into something lifeless, in order that later they might be revived in a way perhaps that was far from edifying. We must therefore regard the direct outpouring (Strömung) from soul to soul as a characteristic feature of the time we are considering. This was an outstanding tendency of the first post-Atlantean epoch, and must be realised if we are to understand, for instance, the old Grecian and Germanic rhapsodists, who moved from place to place reciting their very long poems. If they had employed memory they could never have recited these poems again and again in the same way. It was a soul-force, a soul-attribute far more living than memory, that lay behind these long recitations. To-day if anyone recites a poem he must have learnt it beforehand, but these people experienced what they recited, it was as if newly created at the moment. This was strengthened by the fact that in quite other ways than is the case to-day, the soul-element was then more in evidence. In our day, with some justification, everything of a soul nature is more suppressed. When recitations or lectures are given to-day what matters is the meaning; care is taken as to the meaning of the words. This was not the case when in the middle ages a minstrel recited the Nibelungenlied for example. He had still a certain feeling for the inner rhythm, he even stamped with his foot as he marked its rise and fall. These things were but the echoes of what existed in more ancient times. But you would form no true picture of the Rischis of India and their pupils if you thought they did not communicate the ancient knowledge of Atlantis faithfully. The high school pupil of to-day, even if he wrote out the whole lecture, would not have reproduced what had been said as faithfully as the Indian Rischis reproduced the ancient knowledge in their day. The characteristic feature of the ages that followed is that Atlantean knowledge had ceased to affect them. Up to the decline of the first period, that of ancient Indian culture, the legacy of knowledge man had received continued. Knowledge continued to increase. This came to an end, however, with the first post-Atlantean period, and afterwards hardly anything new came forth from human nature. Increase in knowledge was therefore only possible in the first period, the early Indian, after that it ceased. In the Persian period among those who were influenced by the teaching of Zarathustra, what we can compare with the second age of development in the life of a man began, and it is best understood when so compared. The first period of Indian culture can well he likened to the first part of the life of a man—that from birth to the seventh year—when everything of the nature of form receives its shape, later there is only growth within the established form. Thus it was with the spirit in the first post-Atlantean epoch. What follows later, how man develops the teaching that comes to him in the second part of his life, can be likened to the first period of ancient Persian development and with the instruction then received, only we must be clear as to who the scholars were and who the teachers. I would like to point out something here. Does it not strike you as strange how very differently Zarathustra, the leader of the second post-Atlantean epoch, comes before us to the way, for instance, the Indian Rischis do? While the Rischis appear like holy initiated persons of a far distant age, into whom all the knowledge of ancient Atlantis had poured, Zarathustra comes before us as the first initiate of post-Atlantean times. Something new enters with him. Zarathustra is actually the first historical personality of post-Atlantean times to be initiated into that form of Mystery-knowledge (truly post-Atlantean) in which knowledge was presented in such a way that it was actually comprehensible to the rational understanding of man. What pupils received in those early days in the schools of Zarathustra was pre-eminently a super-sensible knowledge, but it dawned in them so that for the first time it took the form of human conceptions. While it is not possible to reproduce the knowledge of the ancient Rischis in the forms of modern science, this is possible with the knowledge of Zarathustra. Certainly this is a purely super-sensible knowledge, dealing as it does with the super-sensible worlds, but it is clothed in conceptions similar to the conceptions and ideas of post-Atlantean times. Among the followers of Zarathustra a teaching arose of which we can say:—“It was constructed systematically in accordance with the rational conceptions of man.” This means it sprang from the ancient holy treasures of wisdom which evolved up to the end of the Indian period, and continued from generation to generation; no new thing was later added to this, but the old was elaborated further. The mission of the mysteries of the second post-Atlantean period can be realised through a comparison; we can compare it with the publishing of some occult hook. Any book that is the result of investigations into higher world can be clothed in a logical arrangement, thus bringing it down to the physical plane. It is possible to do this. But if my “Outline of Occult Science” had been treated in this way a hook of fifty volumes would have resulted, each as large as the hook itself. If this had been done, each section would have been presented in strictly logical form, this is in the book, and it might have been treated in this way. But it is also possible to proceed otherwise. One can, for instance, leave something to the reader; leave him to think matters out for himself. People must try to do this to-day otherwise the work of occultism could not progress. Now, in the fifth post-Atlantean period, with his acquired powers of forming conceptions, it is possible for man to approach occult knowledge and to increase it, but at the time of Zarathustra, thoughts had first to be discovered capable of dealing with these facts. At that time knowledge such as we have to-day did not exist. Something there was that had remained over like an echo from the time of the Rischis, and to this was added what was capable of being clothed in human thoughts. But human conceptions had first to be found, and into them super-sensible facts had to be poured. Different degrees in power to grasp what was super-sensible then first made its appearance. We may say:—The Rischis still spoke absolutely in the way men had always spoken, in a pictorial language, an imaginative language. They passed on the knowledge they possessed from soul to soul when speaking in this vital picture-language which came whenever they had any kind of super-sensible knowledge to transmit. With “cause and effect” and the other ideas we have to-day with logic in any form—men did not concern themselves in the least. All that arose later. Then in the second post-Atlantean period they began to be interested in super-sensible knowledge. They then felt for the first time the opposition, as it were, of the physical plane; they felt the necessity of giving expression to what was super-sensible so that it might assume forms that thought could grasp on the physical plane. This was the essential mission of the first period of Persian civilisation. Then followed the third period, the period of Egyptian culture. People now had super-sensible ideas. This is difficult for the men of to-day. Try and picture conditions as they were at that time; there was as yet no physical science, but people had ideas that had been gained concerning super-sensible worlds, and they could speak of them in the thought-forms of the physical plane. In the third epoch people began to direct what they had learnt from super-sensible worlds to the physical world. This can again be compared with the third life-period of a man. While in the second life-period he learns; he then goes on to employ what he has learnt. In the third period of their lives most people feel constrained to direct their learning to the physical plane. The pupils of the heavenly knowledge were those who, in the second epoch, had been pupils of Zarathustra, but they now began to direct what they had learnt to the physical plane. Put into modern language we can say—men now learnt that all they beheld through super-sensible vision could only be understood if expressed by a triangle; if they used the triangle as an image to express the super-sensible, they learnt that the super-sensible part of human nature which permeates the physical part can be grasped as a triad. Other conceptions had come to man so that he now applied physical things to what was non-physical. Geometry, for example, was first learnt so that it was accepted as symbolic of ideas. Men had this and made use of it—the Egyptians in the art of surveying and agriculture, the Chaldeans in the study of the stars and the founding of astrology and astronomy. What formerly was held to be only super-sensible was now applied to things seen physically. People began to use what had been born in them as super-sensible wisdom on the physical plane. This was first done in the third cultural period. In the fourth period, the Greco-Latin, this became a fact of outstanding importance. Up to that time men possessed super-sensible knowledge, but did not use it as described. It was not necessary for the Holy Rischis to use it in this way, for knowledge flowed into them directly from the spiritual world. In the time of Zarathustra people had only to ponder over spiritual knowledge, and they knew exactly the form this knowledge would take. In the Egypto-Chaldean age they clothed conceptions from spiritual worlds in what they had gained in physical existence, and in the fourth period they said:—Is it right that what is acquired from the spiritual world should be applied to physical things? Are the things gained in this way really suited to physical conditions? These questions were only put by man to himself in the fourth period after he had used this knowledge innocently, and applied it to his physical requirements for a long time. He then became more self-conscious and asked:—“What right have I to apply spiritual knowledge to physical uses?” Now it always happens that, in an age when any important task has to be carried out, some person appears who can fulfil this task. It was such a person to whom it first occurred to ask the question:—“Have I the right to apply my super-sensible ideas to physical facts?” You can see how what I am trying to indicate developed. You can see, for example, how vital Plato's link still was with the ancient world, how he still used ideas in the ancient form, applying them to physical conditions. It was his pupil, Aristotle, who asked the question—“Ought one to do this?” For this reason he is regarded as the founder of logic. Those who do not concern themselves in any way with spiritual science might ask:—Why did logic arise first in the fourth epoch? Was there not some reason, seeing that evolution had gone on indefinitely, for man to ask himself this question at a specified time? When conditions are really studied, important turning points in evolution are seen to occur at certain times. One such important turning point in evolution occurred between the time of Plato and Aristotle. In this age there was still, in a certain sense, something of the old connection with the spiritual world, as this existed in Atlantean times. Living knowledge certainly died in the Indian epoch; but it was replaced by something new that came from above. Man now became critical and asked:—How can I apply what is super-sensible to physical things? This means: he was then first aware that he could himself accomplish something; observing the world around him he realised that he could bring something down into this world. This was a most important age. We divine (spüren) that conceptions and ideas are super-sensible things when from their nature we begin to perceive in them a guarantee for the super-sensible world. But very few people do perceive this. For most people the fabric of conceptions and ideas is worn very thin and threadbare. Although they may divine that something lives in these which can give them proof of human immortality, conviction is not reached, because the conceptions and ideas concerning the solid reality for which man craves are of such a thin-spun consistency. For most people the fabric they have spun from conceptions and ideas is very thin and worn; though something lives in it which can give them consciousness of immortality, they are incapable of full conviction. But at a time when humanity had sunk to the final—hardly any longer believed in—shreds of that fabric of ideas which it had spun from higher worlds, a mighty new impulse came from the spiritual world and entered into it—this was the Christ-Impulse. The greatest spiritual Reality entered humanity in our post-Atlantean age at a time when man was least spiritually gifted, when all that remained to him was the spiritual gift of ideas. For anyone who studies human development in a wide sense, it is a most interesting consideration, apart from the fact that it affects the soul so overwhelmingly, it is most interesting (even scientifically), to compare the infinite spirituality of that essence which entered human evolution with the Christ Principle, with that which, like a last thin-spun thread from spiritual realms, caused man to ask shortly before: in what way this thread connected him with spirituality. In other words: when we place Aristotelean logic, this weaving of abstract conceptions to which mankind had at last attained, along-side that great Spiritual Outpouring. We can think of no greater disparity than between the spirituality that came down to the physical plane in the Being of Christ, and that which man had preserved for himself. You can therefore understand that in the early Christian centuries it was quite impossible for men to grasp the spiritual nature of Christ with the thin thread of ideas spun from Aristotelean philosophy. Gradually the endeavour arose to grasp the facts of human and world-events in a way conformable to Aristotelean logic. This was the task that faced the philosophy of the middle ages. It is important for us now to compare the fourth post-Atlantean epoch with the fourth period in the life of a man—that period in which the ego develops—to see how the “I am” of all humanity entered human evolution at a time when humanity as a whole was really furthest withdrawn from the spiritual world. This is why man was at first quite incapable of comprehending Christ except through faith; why Christianity had at first to be a matter of faith; only later, and by degrees, was it to become a matter of knowledge. It will become a matter of knowledge; but we have only now begun to enter with understanding into the study of the Gospels. For hundreds and hundreds of years Christianity was only a matter of faith, and had to be so, because than had descended furthest from the spiritual world. As this was man's position in the fourth post-Atlantean period, it was necessary after so deep a descent that he should begin to rise once more. The fourth period brought him furthest on the downward path, but also gave him the first great impulse upwards. Naturally this spiritual impulse could not be understood at first, only in the periods that follow will it be possible for him to understand it. But now we can at least recognise the task before us:—We have to refill our ideas with spirit from within. The evolution of the world is not simple. When, for instance, a ball starts rolling in one direction its momentum tends to make it continue rolling in the same direction. If this is to be changed another impulse must come to give the thrust necessary to a change of direction. Pre-Christian culture had the tendency to continue the downward plunge into the physical world, and has continued to do so to our day. The upward tendency is only beginning, hence the need of a constant incentive to this upward direction. We can see this downward tendency more especially in men's thoughts. The greater part of what is called philosophy to-day is nothing more than the continued downward roll of the ball. Aristotle divined something of this; he grasped the fact that there was a spiritual reality in the fabric of human thoughts. But a couple of centuries after his day, men were no longer capable of realising that the content of the human head was connected with reality. The driest, most desiccated ideas of the old philosophy are those of Kant and everything associated with Kantism. Kant's philosophy puts the main question in such a way that he cuts every link between what man evolves as ideas, between perceptions as an inner life, and that which ideas really are. All this is old and dead, and is therefore not fitted to give any vital uplift for the future. You will now no longer wonder that the conclusion of my lectures on psychology had a theosophical background. I explained that in all we strive for, more especially as regards knowledge of the soul, our task must be to allow ourselves to be so stimulated by this knowledge, given to us formerly by the Gods and brought down by us to earth, that we can offer it up again on the altars of the Gods.: We have only to make the ideas that come to us froth the spiritual world, once more our own. It is not from any want of modesty that I say:—Teaching regarding the soul must of necessity be a scientific teaching, that it must rise again from the frozen state into which it has fallen. There have been many psychologists in the past and there are many still to-day, but the ideas they use are void of spiritual life. It is a significant sign that a man like Franz Brentano be allowed the first volume of his book on Psychology to appear in 1874. Though much it contains is distorted, it is on the whole correct. The second volume was ready, and was to have been published that year, but he was unable to complete it, he stuck in it. He still could give an outline of his teaching, but the spiritual impulse necessary if the work was to be brought to a conclusion was wanting. Such psychologists as we have to-day, Von Wundt and Lipps for example, are not really psychologists for they work only with preconceived ideas; from the first they were incapable of producing anything. Brentano's psychology was fitted to do this, but it remained incomplete. This is the fate of all knowledge that is dying. Death does not enter the domain of natural science so quickly. Here people can work with ideas, for the facts they have accumulated speak for themselves. In the Science of Spirit this does not happen so easily. The whole substratum is immediately lost if people employ ordinary ideas. The muscles of the heart do not immediately cease to beat even if analysed like a mineral product without any recognition of their true nature; but the soul cannot be analysed in this way. Thus science dies from above downwards, and men will gradually reach a point where they will certainly be able to appreciate natural laws, but in a way entirely independent of science. The construction of machines, instruments, telephones and the like, is something very different from understanding science in the right way or carrying it a step further. Anyone can make use of an electric apparatus without necessarily understanding it. True science is gradually dying. We have now reached a point where external science must receive new life from spiritual science. Our fifth period of culture is that in which the ball of science rolls slowly downhill. When it can roll no further its activity will cease, as in the case of Brentano. At the same time the upward progress of humanity must receive ever more life. And it will receive it. This can only happen when efforts are made by which knowledge, even if this has been gained outwardly, becomes fruitful through what occult investigation has to give. Our age, the fifth period, will increasingly assume a character which will show that the ancient Egypto-Chaldean epoch is repeated in it; as yet we have not gone very far with this repetition, it is only beginning. That this is the case can be gathered from what occurred at our annual general meeting. On that occasion Herr Seiler spoke about “Astrology” showing, that as spiritual scientists you were in a position to connect certain conceptions with astrological ideas, whereas this was not possible with the ideas of modern astronomy. Modern astronomy would consider these ideas to be nonsense. This is not because of what astronomical science is in itself, for this science has a better opportunity than any other of being led back to what is spiritual; but because men's thoughts are far removed from any return to spirituality. There is a means, through what astronomy has to offer, by which such a return might easily be made to the fundamental truths of Astrology so undervalued to-day. But some time must elapse before a bridge can he formed between these two. During this time all kinds of theories will be devised, theories by which the movements of the planets, for instance, will be explained in a purely materialistic way. Things will be still more difficult in the domain of chemistry, and in everything connected with life. Here it will he still more difficult to build the bridge. It will he done most easily in the domain of soul-knowledge. To do so it is necessary that people should understand what was stated at the conclusion of my lecture on “Psychology.” There I showed that the stream of soul-life does not only flow from the past towards the future, but also from the future into the past; that we have two time-streams—the etheric part of the life of the soul goes towards the future, the astral part of us on the other hand flows back towards the past. (There is probably no one on the earth to-day who is conscious of this unless he has an impulse towards what is spiritual.) We are first able to form a conception of the life of the soul, when we realise that something comes continually to meet us out of the future. Otherwise this is quite impossible. We must be able to form such a conception, and for this, when speaking of cause and effect, we must break with those ordinary methods of thought which deal mainly with the past. We must not only reckon with the past in such connections, but must speak of the future as something real; something that comes towards us in just as real a way as the past slips from us. But it will be a long time yet before such ideas become prevalent, and till they do there will be no psychology. The nineteenth century produced a smart idea—“Psychology without souls.” People were very proud of this idea, and with it they declared:—“We simply study the revelations of the human soul, but do not concern ourselves with the soul that is the cause of these!” A Soul-teaching without Souls! This can be carried further; but what results (to use a common comparison), is nothing else than a meal time without food. Such is psychology! Now people are of course not satisfied when dinner time comes and the plates are empty; but the science of the nineteenth century was strangely satisfied with the psychology put before it, which was in no way concerned with the soul. This began comparatively early, but into every part of it spiritual life must flow. Therefore we have to record the beginning among us of an entirely new life. The old in a certain sense is finished and a new life must begin. We must feel this. We must feel that a primeval wisdom came to us from ancient Atlantean times, that this gradually declined, and we are now faced with the task of beginning in our present incarnation to gather more and more new wisdom which will be the wisdom of the men of a later day. The coming of the Christ-Impulse made this possible. It will continually develop a living activity, and from it men will perhaps be able best to evolve towards the real, historic Christ, when all tradition concerning Him and all that is outwardly connected with these traditions has died away. From what has been said you can see how the post-Atlantean evolution can actually be compared with the life of a single man; how it is indeed a kind of macrocosm facing man—the microcosm. But the individual man is in a very strange position. What is left to him for the second half of his life of all he acquired in the first half, which when used up is followed by death? The spirit alone can conquer death and carry on to a new incarnation that which gradually begins to decay when we have passed the first half of our life. Our evolution advances until our thirty-fifth year, then it begins to decline. But the spirit then first begins truly to rise! What it is unable to develop further in the second half of life within the body, it brings to completion in a succeeding incarnation. Thus we see the body gradually decline, but the spirit blossom more and more. The macrocosm reveals a picture similar to that of man:—Up to the fourth post-Atlantean epoch we have a youthful upward striving cultural development; from then onwards a real decline; death everywhere as regards the development of human consciousness; but at the same time the dawn of a new spiritual life. The spiritual life of man will be born again in the age following our present one. But he will have to work with full consciousness on what is to be reincarnated. When this happens the other must die, truly die. We gaze prophetically into the future; many sciences have arisen and will arise for the benefit of post-Atlantean civilisation, they, however, belong to what is dying. The life that streamed directly into human life along with the Impulse of Christ will in future rise (ausleben) in man in the same way as Atlantean knowledge rose within the holy Rischis. What ordinary science knows of Copernicus to-day is but the external part of his knowledge, the part belonging to decline. That which will live on, that will be fruitful, not only the part through which he has already worked for four centuries, this part man must win for himself. The teaching of Copernicus as given to-day is not so very true, its truth will first be revealed by spiritual science. So it is as regards much that is held to be most true in astronomy, and so it will be with everything else which men value as knowledge to-day. Certainly, what science discovers to-day is profitable. Therein lies its usefulness. In so far as the science of to-day is technical it is justified; but in so far as it has something to con-tribute to human knowledge, it is a dead product. It is useful for trade, but for that no spiritual content is required. In so far as it seeks to discover anything concerning the mysteries of the universe, it belongs to declining civilisation. In order to enrich our knowledge of the secrets of the universe, external science must super-impose on all it has to offer, the wisdom derived from spiritual science. What I have said to-day can form an introduction to our studies on the Gospel of Mark, which are about to begin. But first I had to speak of the necessity for the entrance into humanity of the greatest Spiritual Impulse of all time at a moment when only the last faint shreds of spirituality remained to it. |

| 119. Macrocosm and Microcosm: Experiences of Initiation in the Northern Mysteries

26 Mar 1910, Vienna Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond, Charles Davy |

|---|

| Only a fantasy-ridden, materialistic mind can believe that it would be possible for a man to originate from the nebula described by the Kant-Laplace theory. Such a nebula could have produced only an automaton—never a man! Around us, we have, firstly, the physical world. |

| Out of indifferent animal organs the light produces an organ to correspond to itself; and so the eye is formed by the light for the light so that the inner light may meet the outer.”] Schopenhauer, and Kant too, want to present the whole world as man's idea; this philosophy seeks to emphasise that without an eye we should perceive no light, that without an eye there would be darkness around us. |

| 119. Macrocosm and Microcosm: Experiences of Initiation in the Northern Mysteries

26 Mar 1910, Vienna Translated by Dorothy S. Osmond, Charles Davy |

|---|

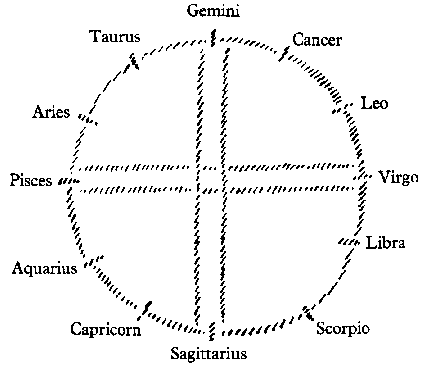

At the conclusion of what was said yesterday on the subject of the deeper mystical path, it was necessary to speak of the chief danger encountered on this path by anyone who attempted to tread it without a leader in times before the methods of Initiation now available, were in existence. In order to indicate still more explicitly how great these difficulties were, I want to add the following.- We have heard that the difficulties are mainly due to the fact that on descending into his inner being, a man becomes almost entirely filled by his egoistic impulses. The Ego awakens with a strength that would place everything in its service; everything would be viewed in accordance with the colouring given it by this reinforced Ego. For this reason it was essential in the process of the ancient Initiation that the strength of the, Ego-feeling, the Ego-consciousness, should be subdued. The Ego had as it were to be given over to the spiritual leader or teacher. This subjugation of the Ego was effected in such a way that through the power emanating from the spiritual leader, the Ego-consciousness of the candidate for Initiation was reduced, to begin with, to one-third of its ordinary strength. That is a very considerable reduction, for it can be said, broadly speaking, that with the exception of the very deepest stage of all, our consciousness in sleep is reduced to about one-third. But in the ancient Mysteries the process was carried further than that; the consciousness was reduced to a quarter of a third (that is, to one-twelfth), so that finally the candidate was actually in a condition resembling death. To outer observation he was exactly like a dead man. But I must emphasise that this Ego-consciousness did not fade away into nothingness. That was not the case. On the contrary, only then was it possible to realise through spiritual perception the intense strength of human egoism; for even when Ego-consciousness was reduced to one-twelfth, a powerful force of egoism still came forth spiritually from the individual. And strange as it may sound, in order to hold in check this outpouring egoism, to keep a spiritual hold on the man whose Ego was thus subdued, twelve helpers were needed for the teacher or leader.—That is one of the so-called secrets of higher Initiation in certain ancient Mysteries. It has been mentioned here only in order that a man may know what is found when he descends into his own inner being. Left to his own resources he would develop traits twelve times worse than those he possessed in ordinary life. These traits were held in check in the ancient Mysteries by the twelve helpers of the priest of Hermes.—This is said merely to supplement the references made at the end of the lecture yesterday. Today we will turn our minds to the other path that a man may take, not by descending into his inner self at the moment of waking, but by consciously experiencing the moment of going to sleep, consciously experiencing the condition during which he is given over to sleep. We have heard how man has then expanded as it were into the Macrocosm, whereas in his waking state he has plunged into his own being, into the Microcosm. We also heard that what a man would experience if his Ego were to pour consciously into the Macrocosm, would be so dazzling, so shattering, that it must be regarded as a wise dispensation that at the moment of going to sleep man forgets his existence altogether and consciousness ceases. What man can experience in the Macrocosm opening out before him, provided he retains a certain degree of consciousness, was described as a state of ecstasy. But it was said at the same time that in ecstasy the Ego is like a tiny drop mingling in a large volume of water and disappearing in it. Man is in the state of being outside himself, outside his ordinary nature; he lets his Ego flow out of him. Ecstasy, therefore, can by no means be considered a desirable way of passing into the Macrocosm, for a man would lose hold of himself and the Ego would cease to control him. Nevertheless in bygone times, particularly in certain parts of Europe, a candidate who was to be initiated into the mysteries of the Macrocosm was put into a condition comparable with ecstasy. This is no longer part of the modern methods for attaining Initiation, but in olden times, especially in the Northern and Western regions of Europe, including our own, it was entirely in keeping with the development of the peoples living there that they should be led to the secrets of the Macrocosm through a form of ecstasy. Thereby they were also exposed to what might be described as the loss of the Ego, but this condition was less perilous in those times because men were still imbued with a certain healthy, elemental strength; unlike people today their soul-forces had not been enfeebled by the effects of highly developed intellectuality. They were able to experience with far greater intensity all the hopefulness connected with Spring, the exultation of Summer, the melancholy of Autumn, the death-shudder of Winter, while still retaining something of their Ego—although not for long. In the case of those who were to become initiates and teachers of men, provision had to be made for this introduction to the Macrocosm to take place in a different way. The reason for this will be evident when it is remembered that the main feature in this process was the loss of the Ego. The Ego became progressively weaker, until finally man reached the state when he lost himself as a human being. How could this be prevented? The force that became weaker in the candidate's own soul, the Ego-force, had to be brought to him from outside. In the Northern Mysteries this was achieved by the candidate being given the support of helpers who in their turn supported the officiating initiator. The presence of a spiritual initiator was essential, but helpers were necessary as well. These helpers were prepared in the following way.— Through a special kind of training, one individual underwent with particular intensity the experiences arising from inner surrender, for example to the budding life of nature in Spring. Certainly, any human being can have something of the same feeling, but not with the necessary intensity. Therefore individuals were specially trained to place all their forces of soul in the service of the Northern Mysteries, to forgo all the experiences connected with Summer, Autumn and Winter, and to concentrate their whole life of feeling on the budding life of Spring. Others again were trained to experience the exuberant life of Summer, others the life characteristic of Autumn, others that of Winter. The experiences which a single human being can have through the course of the year were distributed among a number, so that individuals were available who in very different ways had strengthened one aspect of their Ego. Because they had cultivated one force in particular to the exclusion of all the rest, they had within them a superfluity of Ego-force, and now, in accordance with certain rules, they were brought into contact with the candidate for Initiation in such a way that their superfluity of Ego-force was transmitted to him. His own Ego-force would otherwise have become progressively weaker. Thus the one who in the process of Initiation was to experience the whole cycle of the year, lived through all the seasons with equal intensity; the Ego-force of these helpers of the initiating priest streamed into him so effectively that he was led on to a stage where certain higher truths connected with the Macrocosm were revealed to him. What the others were able to impart poured into the soul of the candidate for Initiation. To understand such a process we must be able to form an idea of the intense devotion and self-sacrifice with which men worked in the Mysteries in those olden times. The exoteric world today has very little conception of such fervent self-sacrifice. In earlier times there were individuals who willingly developed one side of their Ego with the object of placing it at the service of the candidate for Initiation and thus being able eventually to hear from him a description of what he had experienced in a condition that was not ecstasy in the usual sense, but—because extraneous Ego-force had poured into him—a conscious ascent into the Macrocosm. Twelve individuals-three Spring-helpers, three Summer-helpers, three Autumn helpers and three Winter-helpers were necessary; they transmitted their specialised Ego-forces to the candidate for Initiation and he, when he had risen into higher worlds, was able to give information about those worlds from his own experience. A team or ‘college’ of twelve men worked together in the Mysteries in order to help a candidate for Initiation to rise into the Macrocosm. A reminiscence of this has been preserved in certain societies existing today, but in an entirely decadent form. As a rule in such societies special functions are also carried out by twelve members; but this is only a last and moreover entirely misunderstood echo of acts once performed in the Northern Mysteries for the purposes of Initiation. If, then, a man endowed with an Ego-force artificially maintained in him, penetrated into the Macrocosm, he actually ascended through worlds. [* See Note on terminology (at the end of this work) with reference to the different terminology employed for these worlds.] The first world through which he passed was the one that would be revealed to him if he did not lose consciousness on going to sleep. We will therefore now turn our attention to this moment of going to sleep as we did previously to that of waking. The process of going to sleep is in very truth an ascent into the Macrocosm. Even in normal human consciousness it is sometimes possible, through particularly abnormal conditions, to become conscious to a certain extent of the processes connected with going to sleep. This happens in the following way.—The man feels a kind of bliss and can distinguish this consciousness of bliss quite clearly from the ordinary waking consciousness. It is as though he became lighter, as though he were growing out beyond himself. Then this experience is connected with a certain feeling of being tortured by remembrance of the personal faults inhering in the character during life. What arises here as a painful remembrance of personal faults is a very faint reflection of the feeling a man has when he passes the Lesser Guardian of the Threshold and can perceive how imperfect he is and how trivial in face of the great realities and Beings of the Macrocosm. This experience is followed by a kind of convulsion—indicating that the inner man is passing out into the Macrocosm. Such experiences are unusual but known to many people when they were more or less conscious at the moment of going to sleep. But a person who has only the ordinary, normal consciousness loses it at the moment of going to sleep. All the impressions of the day—colours, light, sounds, and so on—vanish, and the man is surrounded by dense darkness instead of the colours and other impressions of daily life. If he were able to maintain his consciousness—as the trained Initiate can do—at the moment when the impressions of the day vanish, he would perceive what is called in spiritual science the Elementary or Elemental World, the World of the Elements. This World of the Elements is, to begin with, hidden from man while he is in process of going to sleep. Just as man's inner being is hidden on waking through his attention being diverted to the impressions of the outer world, so, when he goes to sleep, the nearest world to which he belongs, the first stage of the Macrocosm, the Elementary World, is hidden from his perception. He can learn to gaze into it when he actually ascends into the Macrocosm in the way indicated. To begin with, this Elementary World makes him conscious that everything in his environment, all sense-perceptions and impressions, are an emanation, a manifestation of the spiritual, that the spiritual lies behind everything material. When a man on the way to Initiation—not, therefore, losing consciousness while passing into sleep—perceives this world, no doubt any longer exists for him that spiritual Beings and spiritual realities lie behind the physical world. Only as long as he is aware of nothing except the physical world does he imagine that behind this world there exist all kinds of conjectured material phenomena—such as atoms and the like. For the man who penetrates into the Elementary World there can no longer be any question of whirling, clustering atoms of matter. He knows that what lies behind colours, sounds and so forth is not material but the spiritual. Certainly, at this first stage of the World of the Elements the spiritual does not yet reveal itself in its true form as spirit. Man has before him impressions which, although in a different form from those known in waking consciousness, are not yet the spiritual facts themselves. It is not yet anything that could be called a true spiritual manifestation but to a considerable degree it is something that might be described as a kind of new veil over the spiritual Beings and facts. The form in which this world reveals itself is such that the designations, the names, which since olden times have been used for the Elements are applicable to it. We can describe what is there seen by choosing words used for qualities otherwise perceived in the physical world: solid, liquid or fluid, airy or aeriform, or warmth; or: earth, water, air, fire. These expressions are taken from the physical world for which they are coined. Our language is after all a means of expression for the physical world. If therefore the spiritual scientist has to describe the higher worlds, he must borrow the words from the language that was coined for the things of ordinary life. He can speak only in similes, endeavouring so to choose the words that little by little an idea is evoked of what is perceived by spiritual vision. In depicting the Elementary World we must not take the terms and expressions that are used for circumscribed objects in the physical world but those used for certain qualities common to a category of objects. Otherwise we shall lose our bearings. Things in the physical world reveal themselves to us in certain states which we call solid, liquid, aeriform; and in addition there is also what we become aware of when we touch the surfaces of objects or feel a current of air which we call warmth. Things in the everyday world are revealed to us in these states or conditions: solid, liquid, aecriform or gaseous, or as warmth. These, however, are always qualities of some external body, for an external body may be solid in the form of ice or also be liquid or gaseous when the ice melts. Warmth permeates all three states. So it is in the case of everything existing in the outer world of the senses. The fact is there are not objects in the Elementary World such as are found in the physical world, but in the Elementary World we find as realities what in the physical world are merely qualities. We perceive something there that we feel we cannot approach. The feeling might be described as follows: I have before me something—either an entity or an object of the Elementary World—which I can observe only by going round it; it has an inner and an outer side. Such an entity of the Elementary World is called ‘earth’. Then too there are things and entities which may be described as ‘liquid’ or ‘fluid’. In the Elementary World we can see through them, we can penetrate into them, we have a sensation similar to the sensation in the physical world of dipping the hand into water. We can plunge into them, whereas what is called ‘earth’ is something that offers resistance, like a hard object. The second state is described in the Elementary World as ‘water’. Whenever mention is made of ‘earth’ and ‘water’ in books on spiritual science, this is what is meant; physical water is only an external simile for what is seen at this stage of development. ‘Water’ is something that pours through the Elementary World, not, of course, perceptible to the physical senses, but intelligible to the higher senses, to the faculty of spiritual perception, of the Initiate. Then there is something in the Elementary World comparable with what we call ‘airy’ or ‘aeriform’ in the physical world. This is designated as ‘air’ in the Elementary World. Then, further, there is ‘fire’ or ‘warmth’, but it must be realised that what is called ‘fire’ in the physical world is only a simile. ‘Fire’ as it is in the Elementary World is easier to describe than the other three states for these can really only be described by saying that water, air and earth are similes of them. The ‘fire’ of the Elementary World is easier to describe because everyone has a conception of warmth of soul as it is called, of the warmth that is felt, for example, when we are together with someone we love. What then suffuses the soul and is called warmth, or fire of excitement, must naturally be distinguished from ordinary physical fire which will burn the fingers if they come into contact with it. In daily life, too, man feels that physical fire is a kind of symbol of the fire of soul which, when it lays hold of us, kindles enthusiasm. By thinking of something midway between an outer, physical fire that burns our fingers, and fire of soul, we reach an approximate idea of what is called ‘elemental fire’. When in the process of Initiation a man rises into the Elementary World, he feels as if from certain places something were flowing towards him that pervades him inwardly with warmth, while at another place this is less the case. An added complication is that he feels as if he were within the being who is transmitting the warmth to him. He is united with this elementary being and accordingly feels its fire. Such a man is entering a higher world which gives him impressions hitherto unknown to him in the world of the senses. When a man with normal consciousness goes to sleep his whole being flows out into the Elementary World. He is within everything in that world; but he takes his own nature, what he is as man, into it. He loses his Ego as it pours forth, but what is not Ego—his astral qualities, his desires and passions, his sense of truth or the reverse—all this is carried into the Elementary World. He loses his Ego which in everyday life keeps him in check, which brings order and harmony into the astral body. When he loses the Ego, disorder prevails among the impulses and cravings in his soul and they make their way into the Elementary World together with him; he carries into that world everything that is in his soul. If he has some bad quality, he transmits it to a being in the Elementary World who feels drawn towards this bad quality. Thus with the loss of his Ego he would, on penetrating into the Macrocosm, transmit his whole astral nature to evil beings who pervade the Elementary World. Because he contacts these beings who have strong Egos, while he himself, having lost his Ego, is weaker than they, the consequence is that they will reward him in the negative sense for the sustenance with which he supplies them from his astral nature. When he returns into the physical world they transmit to him, for his Ego, qualities they have received from him and made particularly their own; in other words they strengthen his propensity for evil. So we see that it is a wise dispensation for man to lose consciousness when he enters the Elementary World and to be safeguarded from passing with his Ego into that world. Therefore one who in the ancient Mysteries was to be led into the Elementary World had to be carefully prepared before forces were poured into him by the helpers of the Initiator. This preparation consisted in the imposition of rigorous tests whereby the candidate acquired a stronger moral power of self-conquest. Special value was attached to this attribute. In the case of a mystic, different attributes—humility, for example—were considered particularly valuable. Accordingly upon a man who was to be admitted to an Initiation in these Mysteries, tests were imposed which helped him to rise above disasters of every kind even in physical existence. Formidable dangers were laid along his path. But by overcoming these dangers his soul was to be so strengthened that he was duly prepared when beings confronted him in the Elementary World; he was then strong enough not to succumb to any of their temptations, not to let them get the better of him but to repel them. Those who were to be admitted into the Mysteries were trained in fearlessness and in the power of self-conquest. Once again let it be said at this point that no one need feel alarmed by the description of these Mysteries, for nowadays such tests are no longer imposed, nor are they necessary, because other paths are available. But we shall understand the import of the modern method of Initiation better if we study the experiences undergone in the past by very many human beings in order to achieve Initiation into the secrets of the Mysteries. When the candidate in those ancient Mysteries, after long experiences connected with the Elementary World, had become capable of realizing that ‘earth’, ‘water’, ‘air’, ‘fire’—everything he perceives in the material world—are the revelations of spiritual beings, when he had learned to discriminate between them and to find his bearings in the Elementary World, he could be led a stage further to what is called the World of Spirit behind the Elementary World. Those who were initiates—and this can only be described as a communication of what they experienced—now realised that in very truth there are beings behind the Physical and the Elementary Worlds. But these beings have no resemblance at all to men. Whereas men on the Earth live together in a social order, in certain forms of society, under definite social conditions, whether satisfactory or the reverse, the candidate for Initiation passes into a world in which there are spiritual beings—beings who naturally have no external body but who are related to each other in such a way that order and harmony prevail. It is now revealed to him that he can understand the order and harmony he perceives in that world only by realising that what these spiritual beings do is an external expression of the heavenly bodies in the solar system, of the relationship between the Sun and the planets in their movements and positions. Thereby these heavenly bodies give expression to what the beings of the spiritual world are doing. It has already been said that our solar system may be conceived as a great cosmic clock or timepiece. Just as we infer from the position of the hands of a clock that something is happening, we can do the same from the relative positions of the heavenly bodies. Anyone looking at a clock is naturally not interested in the hands or their position per se, but in what this indicates in the outer world. The hands of a clock indicate, for example, what is happening here in Vienna or somewhere in the world at this moment. A man who has to go to his daily work looks at the clock to see if it is time to start. The position of the hands is therefore the expression of something lying behind. And so it is in the case of the solar system. This great cosmic clock can be regarded as the expression of spiritual happenings and of the activity of spiritual beings behind it. At this stage the candidate for the Initiation we have been describing comes to know the spiritual beings and facts. He comes to know the World of Spirit and realises that this World of Spirit can best be understood by applying to it the designations used in connection with our solar system; for there we have an outer symbol of this World of Spirit. For the Elementary World the similes are taken from the qualities of earthly things—solid, liquid, airy, fiery. But for the World of Spirit other similes must be used, similes drawn from the starry heavens. And now we can realise that the comparison with a clock is by no means far fetched. We relate the heavenly bodies of our solar system to the twelve constellations of the Zodiac, and we can find our bearings in the World of Spirit only by viewing it in such a way as to be able to assert that spiritual Beings and events are realities; we compare the facts with the courses of the planets but the spiritual Beings with the twelve constellations of the Zodiac. If we contemplate the planets in space and the zodiacal constellations, if we conceive the movements and relative positions of the planets in front of the various constellations to be manifestations of the activities of the spiritual Beings and the twelve constellations of the Zodiac as the spiritual Beings themselves, then it is possible to express by such an analogy what is happening in the World of Spirit. We distinguish seven planets moving and performing deeds, and twelve zodiacal constellations at rest behind them. We conceive that the spiritual facts—the courses of the planets—are brought about by twelve Beings. Only in this way is it possible to speak truly of the World of Spirit lying behind the Elementary World. We must picture not merely twelve zodiacal constellations, but Beings, actually categories of Beings, and not merely seven planets, but spiritual facts. Twelve Beings are acting, are entering into relationship with one another and if we describe their actions this will show what is coming to pass in the World of Spirit. Accordingly, whatever has reference to the Beings must be related in some way to the number twelve; whatever hag reference to the facts must be related to the number seven. Only instead of the names of the zodiacal constellations we need to have the names of the corresponding Beings. In Spiritual Science these names have always been known. At the beginning of the Christian era there was an esoteric School which adopted the following names for the Spiritual Beings corresponding to the zodiacal constellations: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Kyriotetes, Dynameis, Exusiai, then Archai (Primal Beginnings or Spirits of Personality), then Archangels and Angels. The tenth category is Man himself at his present stage of evolution. These names denote ten ranks. Man, however, develops onwards and subsequently reaches stages already attained by other Beings. Therefore one day he will also be instrumental in forming an eleventh and a twelfth category. In this sense we must think of twelve spiritual Beings. If we wanted to describe the World of Spirit we should have to attribute the origin of the spiritual universe to the co-operation among these twelve categories of Beings. Any description of what they do would have to deal with the planetary bodies and their movements. Let us assume that the Spirits of Will (the Thrones) co-operate with the Spirits of Personality (Archai) or with other Beings—and Old Saturn comes into existence. Through the co-operation of other Spirits the planetary bodies we call Old Sun and Old Moon come into existence. We are speaking here of the deeds of these spiritual Beings. A description of the World of Spirit must include the Elementary World, for that is the last manifestation before the physical world; fire, air, water, earth, must also be considered. On Old Saturn, everything was fire or warmth; during the Old Sun evolution, air was added; during the Old Moon evolution, water. In describing the World of Spirit we must begin with the Beings. We call them the Hierarchies and pass on to their deeds which come to expression through the planets in their courses. And to have a picture of how all this manifests in the Elementary World we must describe it by using terms derived from this world. Only in this way is it possible to give a picture of the World of Spirit lying behind the Elementary World and our physical world of sense. The Beings, the spiritual Hierarchies, their correspondences with the zodiacal constellations, the planetary embodiments of our Earth described by using expressions connected with the Elementary World-all this is presented in detail in the chapter on the evolution of the world in the book Occult Science—an Outline,1 and we can now understand the deeper reasons for that chapter having been written in the way it has. It describes the Macrocosm as it should be described. Any real description must go back to the spiritual Beings. I tried in the book Occult Science to give guiding lines for the right kind of description of the World of Spirit—the world entered when there has been an actual ascent into the Macrocosm. This ascent into the Macrocosm can of course proceed to still higher stages, for the Macrocosm has by no means been exhaustively portrayed by what has here been said. Man can ascend into even higher worlds; but it becomes more and more difficult to convey any idea of these worlds. The higher the ascent, the more difficult this becomes. If we want to give an idea of a still higher world it must be done rather differently. An impression of the world that is reached after passing beyond the World of Spirit may be obtained in the following way.—In describing man as he stands before us we may say that his existence was only made possible through the existence of these higher worlds. Man has become the being he is because he has evolved out of the physical world but above all out of the higher, spiritual worlds. Only a fantasy-ridden, materialistic mind can believe that it would be possible for a man to originate from the nebula described by the Kant-Laplace theory. Such a nebula could have produced only an automaton—never a man! Around us, we have, firstly, the physical world. The physical body of man belongs to the world we perceive with our senses. With ordinary consciousness we perceive it only from outside. To what world do the more deeply lying, invisible members of man's nature belong? They all belong to the higher worlds. Just as with physical eyes we see only the material aspect of man, so too we see of the great outer world only what the senses perceive; we do not see those super-sensible worlds of which two—the Elementary World and the World of Spirit—have been described. But man, with his inner constitution, has issued from these higher worlds. The whole of man's being, his external, bodily nature too, has become possible only because certain invisible spiritual Beings have worked on him. If the etheric body alone had worked on man, he would be like a plant, for a plant has a physical and an etheric body. Man has in addition the astral body; but so too has the animal. If man had only these three members (physical body, etheric body, astral body) he would be an animal. It is because man has his Ego as well that he towers above these lower creatures of the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms of nature. All the higher members of man work on his physical body; the physical body could not be what it is unless man also possessed these higher members. A plant would be a mineral if it had no etheric body. Man would have no nervous system if he had no astral body; he would not have his present structure, his upright gait, his over-arching brow, if he had not an Ego. If he had not his invisible members in higher worlds, he could not confront us as the figure he is. Now these different members of man's organism and constitution have been formed out of different spiritual worlds. To understand this we shall do well to remind ourselves of a beautiful, profoundly wise saying of Goethe: “The eye is formed by the light for the light.” [* See Goethe's Studies in Natural Science. (Kürschner, Nationalliteratur, Vol. 35, p. 88). “The eye owes its existence to the light. Out of indifferent animal organs the light produces an organ to correspond to itself; and so the eye is formed by the light for the light so that the inner light may meet the outer.”] Schopenhauer, and Kant too, want to present the whole world as man's idea; this philosophy seeks to emphasise that without an eye we should perceive no light, that without an eye there would be darkness around us. That, of course, is true, but the point is that it is a one-sided truth. Unless the other side is added a one-sided truth is being regarded as the whole truth—than which there is nothing more pernicious. To say something that is incorrect is not the worst thing that can happen, for the world itself will soon put one right about it; but it is really serious to regard a one-sided truth as the absolute truth and to persist in so regarding it. That without the eye we could see no light is a one-sided truth. But if the world had remained forever filled with darkness, we should have had no eyes. When animals have lived for long ages in dark caves they lose their sight and their eyes go to ruin. On the one side it is true that without eyes we could gee no light, but on the other side it is equally true that the eyes have been formed by the light, for the light. It is always essential to look at truths not only from the one side but also from the other. The fault of most philosophers is not that they say what is false—in many cases their assertions cannot be refuted because they do state truths—but that they make statements which are due to things having been viewed from one side only. If you take in the right sense the saying that “the eye is formed by the light, for the light”, you will be able to say to yourselves that there must be something in the light that admittedly we do not see with our eyes but that has developed the eyes out of an organism which at first had no eyes. Behind the light there is something hidden. Let us say here: The eye-forming power is contained in every ray of sunlight. From this we can realise that everything round about us contains the forces which have created us. Just as our eyes are created by something within the light, all our organs have been formed by something that underlies everything we see in the world outside as external surfaces only. Now man also has intellect, intelligence. In physical life he is able to use his intelligence because he has an instrument for it. Remember, we are speaking now of the physical world, not of what becomes of our thinking when we are free of the body after death, but of how we think through the instrument of the brain when we have wakened from sleep in the morning; after waking we see light through the eyes. In the light there is something that has formed the eye. We think through the instrument of the brain; thus there must be something in the world that has formed the brain in such a way that it could become an instrument of thinking suitable for the physical world. The brain has been made into an organ of thinking for the physical world by the power which manifests externally in our intelligence. Just as the light we perceive with the eye is an eye-forming power, our brain is the surface manifestation of a brain-forming power or force. Our brain is formed from out of the World of Spirit. One who has attained Initiation recognises that if only the Elementary World and the World of Spirit existed, man's organ of intelligence could never have come into being. The World of the Spirit is indeed a lofty world but the forces which have formed the physical organ of thinking must have streamed into man from a yet higher world in order that intelligence might manifest outwardly, in the physical world. Spiritual science has not without reason figuratively expressed this frontier of the world we have described as the world of the Hierarchies, by the word “Zodiac.” Man would be at the level of the animal if only the two worlds that have been described were in existence. In order that man could become a being able to walk upright, to think by means of the brain and to develop intelligence, an in-streaming of even higher forces was necessary, forces from a world above the World of Spirit. Here we come to a world designated by a word that is totally misused today because of the prevailing materialism. But in a past by no means very distant the word still conveyed its original meaning. The faculty man unfolds here in the physical world when he thinks, was called ‘Intelligence’ in the spiritual science of that earlier period. It is from a world lying beyond both the World of Spirit and the Elementary World that forces stream down through these two worlds to build our brain. Spiritual Science has also called it the World of Reason (Vernunftwelt). It is the world in which there are spiritual Beings who are able to send down their power into the physical world in order that a shadow-image of the Spiritual may be produced in the physical world in man's intellectual activity. Before the age of materialism no one would have used the word “reason” for thinking; thinking would have been called intellect, intelligence. “Reason” (Vernunft) would have been spoken of when those who were initiates had risen into a world even higher than the World of Spirit and had direct perception there. In the German language “reason” is connected with perception (Vernehmen), with what is directly apprehended, perceived as coming from a world still higher than the one denoted as the World of Spirit. A faint image of this world exists in the shadowy human intellect. The architects and builders of our organ of intellect must be sought in the World of Reason. It is only possible to describe a still higher world by developing a spiritual faculty transcending the physical intellect. There is a higher form of consciousness, namely, clairvoyant consciousness. If we ask: how is the organ evolved which enables us to have clairvoyant consciousness?—the answer is that there must be worlds from which emanate the forces necessary for the development of this clairvoyant consciousness. Like everything else, it must be formed from a higher world. The first kind of clairvoyant consciousness to develop is a picture-consciousness, Imaginative Consciousness. This Imaginative Consciousness remains mere phantasy only for as long as the organ for it is not formed by forces from a world lying beyond even the World of Reason. As soon as we admit the existence of clairvoyant consciousness we must also admit the existence of a world from which emanate the forces enabling the organ for it to develop. This is the World of Archetypal Images (Urbilderwelt). Whatever can arise as true Imagination is a reflection of the World of Archetypal Images. Thus we rise into the Macrocosm through four higher worlds: the Elementary World, the World of Spirit, the World of Reason and the World of Archetypal Images. In the next lectures I will deal with the World of Reason and the World of Archetypal Images and then describe the methods by which, in line with modern culture, the forces from the World of Archetypal Images can be brought down in order to make possible the development of clairvoyant consciousness.

|

| 140. Occult Research into Life Between Death and a New Birth: The Establishment of Mutual Relations between the Living and the So-called Dead

20 Feb 1913, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Hofrichter |

|---|

| On one occasion I met a man who was otherwise not really very smart, but who, nevertheless, talked incessantly about Kant, Schopenhauer, and so forth who even gave lectures on Kant and Schopenhauer. This man, when I lectured about the nature of immortality, answered me in a rather smug way. |

| 140. Occult Research into Life Between Death and a New Birth: The Establishment of Mutual Relations between the Living and the So-called Dead

20 Feb 1913, Stuttgart Translated by Ruth Hofrichter |

|---|