| 158. Concerning the Origin and Nature of the Finnish Nation

09 Nov 1914, Dornach Translator Unknown |

|---|

| But it will be grasped, when the teachings of Anthroposophy will be used in a corresponding way, in order to explain the spiritual phenomena of the evolution of the earth. |

| 158. Concerning the Origin and Nature of the Finnish Nation

09 Nov 1914, Dornach Translator Unknown |

|---|

If there is a sphere in the human soul that really constitutes a kind of triad, which, in the case of modern man, is, as it were, covered by his ordinary consciousness, we should also be able to find in evolution a stage that reveals this outwardly; that is to say, a stage in which the soul really feels its threefold nature and in which the three members of the soul appear separately. In other words: A nation must once have existed that felt these soul-parts separately, in such a way that the “one-ness” was, after all, felt within the soul far less than the “threefold-ness”, and so that this threefold nature of the soul was still thought of in connection with the cosmos. Such a nation really existed in Europe and it left behind an important monument of culture, concerning which I have already spoken to you. This nation once experienced within the soul the soul's threefold character—and just there, where it should exist—and this was the Finnish nation. This stage of culture is expressed in the epic poem “Kalevala”. What is set forth in “Kalevala”, contains a clear consciousness of the soul’s threefold nature. Thus, the ancient seers, upon whose visionary power the “Kalevala” is based, felt: “The world contains an inspiring element and one of the members of my soul is connected with it; my sentient soul receives its impulses from there.” This nation, or these ancient seers, experienced the inspiring element of the sentient soul almost as a human-divine, or a human-heroic essence, and they called it “Wainamoinen”. This is nothing but the inspiring element of the sentient soul, inspiring it from out [of] the cosmos, and all the destinies of Wainamoinen, described in “Kalevala”, express the fact that this form of consciousness once existed in a nation that was widely spread in the north-eastern territory of Europe, a nation that experienced the three parts of the soul separately and felt that the sentient soul was inspired by Wainamoinen. In the same way, this nation, or these ancient seers, felt that the understanding soul was, as it were, a special member of the soul, that receives its forging impulses—or that which forges within the soul and builds it up—from another Being, called Ilmarinen. Just as in the Kalevala Wainamoinen corresponds to the sentient soul, so Ilmarinen corresponds to the understanding soul. If you read my lecture on “Kalevala”, you will find in it all these explanations. In the same way, that nation, or those ancient seers (but we must bear in mind the fact that the consciousness-soul was, at that time, experienced as something that enabled the human being to be a conqueror upon the physical plane) experienced that Lemminkainen was a Being connected with the powers of the physical plane, an elemental, heroic Being, the inspirator of the consciousness-soul. Thus, if we speak in accordance with other epic poems, we may say that these three heroic characters come from the Finnish nation and inspire the threefold nature of the soul. Wonderful is the relationship between Ilmarinen and what is being forged there. I have already pointed out that in “Kalevala” the human being is forged out of the various elements of Nature. In “Kalevala”, this Being, forged, as it were, out of all the atoms of Nature, the Being that is pulverised, and then forged together, is described in a marvellous picture as the forging of Sampo. The fact that once upon a time the human being was really formed out of these three soul-parts and then passed over, as it were, into a “pralaya”, in order to emerge again later on, all this is described in “Kalevala” in the part where Sampo is lost and found again: it is, as it were, the re-discovery of something over which the darkness of consciousness was first spread out. Let us now imagine that in the south, or rather in the southeast, another nation faces the Finnish nation, one that developed in ancient times the soul-qualities mentioned to you: a uniform character of the soul, a soul-element expressing this uniform character in the qualities of its character, feeling and temperament. This nation is a Slav nation, influenced by Scythianos, who lived in the remote past for some time in the environment of the ancient Scythian nation. However, a nation living in the neighbourhood of a centre of initiation need not at all be a highly developed nation, but instead, the necessary things must take place in the course of evolution. With the penetration of the Graeco-Byzantine culture into Slavism, a particular form of the Mystery of Golgotha also penetrated into it. What I have indicated, here, as the centre of the Graeco-Byzantine culture, may be taken, if you like, as Constantinople on the map of Europe, for it is, after all, Constantinople. Thus we have before us souls impregnated with a fundamentally Slav type, souls that are, on the one hand, connected with something that can lead, through the Mystery of Golgotha, to a uniform soul-essence and may thus prepare these souls having a uniform character for Christianity, and on the other hand, these souls take up the Mystery of Golgotha in a very definite form, resembling an inspiration or an influence coming from the Mystery of Golgotha, in the form in which it went out of the Graeco-Byzantine culture. But something else must now take place. The following thing must, as it were, come from a certain point.—The separation that existed in the Finnish nation, the division of the three soul-parts, set forth so wonderfully in “Kalevala”, must now be obliterated. This can only be obliterated through an influence from outside; it can only be obliterated through the circumstance of an advancing nation, or part of nation, predisposed from the very outset to experience within the soul its “one-ness”, not its “threefold-ness”, but this “one-ness” is not the one obtained through the Mystery of Golgotha, but a kind that this nation possessed through its own nature. If we study the Finnish nation, we shall find that it is particularly disposed to develop the consciousness of the soul’s threefold character; this threefold character and its connection with the cosmos cannot be expressed more significantly than it has been expressed in “Kalevala”. But in the north, this had to be whitewashed, it had to be clouded over, as it were, by something that obliterates the consciousness of the soul’s threefold nature. And so a race descends, that bears within its soul, in a natural form, the strivings after unity, in the manner in which they existed at that time—expressed in an entirely different way and on an entirely different stage in “Faust”, in Goethe's “Faust”, and in the character of Faust, in general—it bears within its soul something that entirely ignores the soul’s threefold nature, striving after the unity of the Ego. At this still primitive stage, it has a destructive effect upon the three soul-members. But the Finnish nation was of such a kind that it could still feel in a natural way the streaming forces that penetrated into the soul’s “threefoldness”, obliterating it. (Otherwise it would not have been able to experience these three members of the soul). This streaming-element, forcing its way into the soul, was experienced as a threefold R, as RRR. And just because it was experienced as something which in occult language is best of all expressed in the letters, or in the sound “UUO”, inducing one to say, it comes along, and one should really be afraid of it—it now streams along as a breath in the sound “RRRUUO” and becomes, rooted in what is always experienced through the “TAO” (T), when it penetrates into the human soul. In the case of the ancient divinity Jehova, the penetration into the human soul was expressed with the sound “S”, or the Hebrew “Shin”, and the penetrating element in general is expressed, with the “S” sound. This is connected with the element that penetrates into the soul. What takes root in the soul, tends towards the sound “I”, (pronounced EE), whose significance is well known. Consequently, the Finnish nation experienced this in the sound “RUOTSI”, and for this reason it called the descending nations the “RUTSI” (Ruotsi). The Slavs then gradually adopted this name, and because they connected themselves with that element, penetrating, as the Finns called it, downwards from above, they also called themselves “Rutsi”, which afterwards became the name of the “Russians”. Thus you may see that the external events described in history had to take place. The fact that the nations that were settled down here, below, called in the Warager tribes—in reality, they were Norman-German tribes who had to connect themselves with the Slav tribes—is entirely connected with something that had to take place; it had to occur, in accordance with the constitution of the human soul. In the East of Europe thus arose later on that element which penetrated into the nations of Europe as the Russian element, the Russian nation. The Russian element therefore contains all those things which I mentioned: it contains, above all, a Norman-German element, and this lives in the name from which the name “Russians” descends, for it has arisen in the way described just now. The “Kalevala” expresses in a deep way that the greatness of the Finnish nation is based on the fact that it really prepares the “one-ness”, or the unity within the triad; by obliterating the soul’s threefold character it prepares the acceptance of that unity which is no longer a purely human unity, but a divine one, in which dwells the godly hero of the Mystery of Golgotha. In order that a group of men may take up what comes towards it, it must first be prepared for this. We may, thus, gain an impression of all that had to occur inwardly, in order that the things, which we then encounter inwardly, may arise in the course of development. I explained to you that “Kalevala” expresses in a wonderful way the truth that the Finnish nation had to supply this preparation, in view of the fact that the Mystery of Golgotha is introduced in a strange way at the end of the poem. Christ appears at the end of “Kalevala”, but because he throws his impulse into Finnish life, Wainamoinen abandons the country, and this expresses that the originally great and significant element that penetrated into Europe through the Finnish element, was a preparatory stage for Christianity and took up Christianity like a message from outside. Just as an individual human being must be prepared in an extraordinarily complicated manner, as it were, so that his soul may find from various sides what it requires, in order to live within a definite incarnation, so it is also the case with nations. A nation is not an entirely uniform, homogeneous element, but something in which many elements flow together. All manner of things have flown together in the nation that lived yonder in the East. Indeed, we may say that everything of an inwardly spiritual character is, at the same time, indicated outwardly, even though it is only indicated slightly. I said that in this nation we must look out for a soul-tribe leading upwards from below; respectively, also downwards from above, in the case of a connecting soul-tribe. This was actually the case, for a powerful stream, a great road went from the Black Sea to the Finnish Bay and along this road an exchange took place between the Graeco-Byzantine element and that which constituted the natural element of the “Rutsi”. Last time I told you that Europe’s Eastern culture was preceded, let us say, by a cultural stratum in which the human beings were constituted in such a way that they still possessed in their souls something that has more withdrawn into subconscious spheres in the case of modern man, and that they experienced in their ordinary life something like a division of the soul into sentient soul, understanding soul and consciousness-soul. I explained to you that the men belonging to the once great Finnish nation (the present one is only a remnant of the formerly great and widely spread nation) had souls that possessed, in addition to a certain ancient form of clairvoyance, in their immediate daytime experience, something like a scission of the soul into sentient soul, understanding soul and consciousness-soul. I told you that in the magnificent epic poem “Kalevala” the three characters Wainamoinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkainen express how this threefold soul is structured and guided from out the cosmos. How could such a thing take place? How was it possible that a great nation could develop at a certain place in Europe, a nation whose soul was of the kind described to you? That the human being develops his true Ego, the gift of the earth, depends upon the fact that the spirits of the earth influence him from below, through the Maya of earthly substance. The spirits of the earth work from below, through the solid earth, as it were, and in our time these spirits of the earth are essentially used for the purpose of calling forth in the human being his Ego-nature. When something that lies below the Ego-nature rays into a nation such as the old Finnish nation, something more spiritual than the Ego-nature and more strongly connected with the divine forces, (for, if the soul feels itself split into three, it is more strongly connected with the divine powers than if this is not the case) then not only the earthly element, with its elemental spirits, can, in a certain way, ray into man’s earthly part from below, but something else must ray into this earthly element, another elemental influence must ray into it. Just as man’s physical existence is intimately connected with the spirit of the earth—in so far as this existence is an earthly one and in so far as he develops his Ego within it—that is to say, with the spirits working upwards from below, from the earth itself, so man’s soul-element, revealing itself as an existence connected with his nature, temperament, character and soul, is related with everything that lives upon the earth in the form of watery element, of liquid, element. Consequently, these souls that are split into three parts must be influenced by spirits pertaining to the watery, to the liquid element. The essential element of our time is the earthly element, the Ego-forming element. When another element penetrates into us, for instance the watery element, then it penetrates more from out the spiritual world. It is not contained in the human being himself. It must, as it were, penetrate into man as a spiritual being, so that man’s earthly nature may obtain something that leads him into the spiritual world. Suppose that the surface of this blackboard represents that out of which come the elemental forces of the earth; in that case, a spiritual element that seeks to penetrate in there, must come out of the organism of the earth itself out of something that is, in itself, spiritual: a Being must be there, a real Being, that is not the human being, but inspires the human being, as it were, to experience the threefold split of his soul. Consequently, a being must be there that influences the soul from out [of] the spirituality of Nature in such a way that the sentient soul, the understanding soul and the consciousness-soul separate and so that the souls are really able to say: My sentient soul is influenced from out Nature by a force resembling Wainamoinen; it streams towards me like a being of Nature and endows me with the force of the sentient soul. But that is still another influence, resembling Ilmarinen, that endows me with the forces of the understanding-soul, and there is moreover something that resembles Lemminkainen, endowing me with the forces of the consciousness-soul. If HERE, at this place, *) we have a being stretching out, as it were, its feelers into Nature, almost through a kind of neck, if a being that has, as it were, its chief group-body HERE, at this place, and that stretches out its feelers in such a way that we have one of them here, together with the sentient soul, a second feeler there, and a third one there, then this being of Nature would have a body and its soul-part would penetrate, as if with soul-feelers, into these places, in order to exercise an inspiring influence—and there, etheric bodies can arise, that enable the soul to feel itself split into three. The ancient Finnish population used to say: We live here, yet we feel something resembling three powerful beings, that do not belong to the physical plane, but are beings of Nature. They reveal themselves, coming from the West; they are three parts, almost organs of one might being, whose body lives yonder, but that stretches out its feelers in this direction. (Wainamoinen, Ilmarinen, Lemminkainen.) A powerful OCEAN-BEING spreads from west to east; it stretches out its feelers and endows this nation with that which constitutes the threefold soul. The nations who still experienced this, felt and spoke in this way, and also “Kalevala” speaks in this manner, as explained just now. Modern man, who merely lives upon the physical plane, says that the western sea stretches out as far as this place: Here is the Gulf of Bothnia, the Finnish Gulf and the Gulf of Riga. But in trying to gain an insight into the spiritual essence of the external physical aspect, we simply take together what appears to us like a transverse section of Nature: we take together the following things and say: There is still a great quantity of water, there below; beyond there is the air; man breathes in the air, and this ocean world is a great powerful being that is simply structured in a different way than the one to which we are accustomed. What is spread out over there is a powerful being, and the human beings belonging to that older race were connected with it in a very marked, and distinctly outlined way. And when we speak of Folk-Souls, these Folk-Souls have in the elemental spirits that exist in countless of these soul-expressions, the instruments through which they can work. They organise, as it were, an army in order to penetrate with their influence as far as the etheric body, and to mould man, through the etheric body, in such away that his physical body becomes an instrument for that which is to be his particular and special mission upon the earth. We can understand culture, even in its relation to man, only if we can contemplate the forms that we encounter in Nature as an expression of the spirit, we can understand it, if we do not contemplate the sea and land boundaries in the usual thoughtless manner, but if we are able to understand what these forms express. Someone who sees the face of a person might say, for instance: The face has certain definite forms; flesh and air contact one another. But if he describes it in this way, it will be difficult to know what the face was really like. We can only understand it if we consider it as the expression, as the countenance of the human being. Similarly, in the above-mentioned case, we can only grasp things if we consider them as the physiognomy of a powerful being that stretches certain parts of its principal body out of the ocean that stretches out this part of its physiognomy. Indeed, many things occur below the threshold of consciousness and the Spirits of Form have not in vain set definite forms into Nature. It is possible to grasp the meaning of these forms. They are the expression of an inner being. And if we become the pupils of the Spirits of Form, we ourselves can create forms expressing that which lives in the inner being of Nature and of the Spirit. I explained to you that there is a certain relationship in which East and West work together, in which the liquid element leans towards the East, as if it were a powerful Being and, as an expression of the threefold nature of the soul, it leans over in the three great Bays, that were still experienced by the more spiritual nations of ancient Finland as Wainamoinen, Ilmarinen and Lemminkainen, and are to-day designated so prosaically as the Finnish, the Bothnian and the Riga Bays. What comes out of the liquid and out of the solid elements, worked together in the Finnish nation. Within it were united the element that moulds more the etheric part of man and refines his physical part, namely, the liquid element, and the element of the earth, or that which comes out of the earth and forms the physical part of man. We might now ask: What significance has the fact that a nation that fulfilled so eminent a mission in the course of the earth’s evolution as that of the great Finnish nation, should still exist after having accomplished its task? The fact that such a nation remains, that it does not disappear after having fulfilled its mission, has its meaning within the whole progress of evolution. Just as a human being preserves in his living memory, for his subsequent life, the thoughts which he formed at some earlier time of life, so the nations of a past time must remain, almost like a conscience, like a living memory that continues to be active in the face of what happens later—LIKE A CONSCIENCE. Now we might say: The conscience of Eastern Europe is the force that preserved the Finnish nation. But a time must come when the understanding for the tasks of evolution will take hold of human hearts, when the ideas of “Kalevala” will begin to blossom from out the midst of the Finnish nation itself, when this wonderful epic poem will be spiritualised and permeated with modern anthroposophical ideas, so that it will once more reach, in all its depth, the consciousness of the whole of Europe. The European nations revered Homer’s epic poems. Yet the “Kalevala” streamed out of still deeper sources of the soul’s life. This cannot as yet be grasped. But it will be grasped, when the teachings of Anthroposophy will be used in a corresponding way, in order to explain the spiritual phenomena of the evolution of the earth. An epic poem such as “Kalevala”, cannot be preserved unless it is preserved in a living form of existence; it cannot be preserved without souls that dwell in human bodies, souls that are related with the creative forces of “Kalevala.” “Kalevala” remains as a living conscience. Its influence can continue, because, not the words, but that which lives in the poem itself, continues to live. Its influence can continue through the fact that a centre exists, from which it may ray out. The essential thing is that this centre should be there, in the same way in which the thoughts that we have had at some earlier time of our life, still exist later on in life. |

| 317. Curative Education: Lecture XII

07 Jul 1924, Dornach Translated by Mary Adams |

|---|

| You see from all this how closely, how livingly interlinked the different activities have to be in Anthroposophy. It will thus be necessary to take care that the work you are initiating at Lauenstein—a work, let me say, that I regard as full of hope and promise—is carried on in entire harmony with the whole Anthroposophical Movement. |

| 317. Curative Education: Lecture XII

07 Jul 1924, Dornach Translated by Mary Adams |

|---|

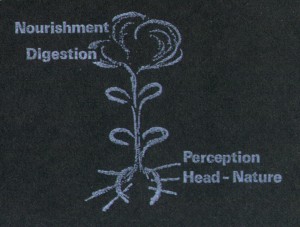

What we have really been endeavouring to do in our talks together here is to delve a little more deeply into Waldorf School pedagogy, in order to find in that pedagogy the kind of education with which we can approach the so-called abnormal child. It will have been clear to you from our discussions that, if you want to educate an abnormal child in the right manner, you will have to form your judgement and estimation of him in quite another way than you do for the so-called normal child—and of course differently again from the way he is regarded in ordinary lay circles, where people are for the most part content merely to specify the abnormality and not trouble themselves to look further and enquire into the causes of it. For there is no denying it, the man of today is not nearly so far on (in his study, for example, of the human being), as Goethe was in his study of the growth and nature of the plant. (And, as we saw, Goethe's work in this direction was a beginning, it was still in its elementary stage.) For Goethe took a special delight in the malformations that can occur in plants; and the passages where he deals with such are among the most interesting in all his writings. He describes, for example, how some organ in a plant, which one is accustomed to find in a certain so-called normal form, may either grow to excess, becoming abnormally large, or may insert itself into the plant in an abnormal manner, sometimes even going so far as to produce from itself organs that would normally be situated in quite another part of the plant. In the very fact that the plant is able to express itself in such malformations, Goethe sees a favourable starting point for setting out to discover the true “idea” of the archetypal plant. For he knows that the idea which lies hidden behind the plant manifests quite particularly in these malformations; so that if we were to carry out a whole series of observations—it would of course be necessary to make the observations over a wide range of plants—if we were to observe first how the root can suffer malformation, then again how the leaf, the stem, the flower, and even the fruit can become deformed, we would be able, by looking upon all these malformations together, to arrive at an apperception of the archetypal plant. And it is fundamentally the same with all living entities—even with beings who live in the spirit. More and more does our observation of the human race lead us to perceive this truth—that where we have abnormalities in man, it is the spirituality in him which is finding expression in these abnormalities. When once we begin to look at the phenomena of life from this aspect, it will at the same time give us insight into the way men thought about life in olden times; and we shall understand how it was that education was regarded as having an extremely close affinity with healing. For in healing men saw a process whereby that in man which has received Ahrimanic or Luciferic form and configuration is made to come nearer to that in him which, in the sense of good spiritual progress, holds a middle course between the two extremes. Healing was, in effect, the establishment of a right balance in the human being between the Ahrimanic and the Luciferic. And then, having a more intimate and deep perception of how it is only in the course of life that man comes into this condition of balance, of how he needs indeed to be brought into it by means of education, these men of an older time saw that there is something definitely abnormal about a child as such, something in every child that is in a certain respect ill and requires to be healed. Hence the primeval words for “healing” and “educating” have the very same significance. Education heals the so-called normal human being, and healing is a specialised form of education for the so-called abnormal human being. If it has become clear to us that the foregoing is a true and fundamental perception, we can do no other than carry our enquiry further along the same road. All the illnesses that originate within the human being have, in reality, to do with the spiritual in him, and ultimately even the illnesses that arise in him in response to an injury from without; for when you break your leg, the condition that presents itself is really the reaction that arises within you to the blow from without—and surgery could certainly learn something by looking at the matter in this light. Starting therefore from this fundamental perception, we find ourselves ready to approach in a much deeper and more intimate manner the question: How are we to deal with children, having regard to the whole relationship of their physical nature to their soul and spirit? In the very young child, physical and spiritual are intimately bound up together, and we must not assume—as people generally do today—that when some medicament or other is given to a child, it takes effect physically alone. The spiritual influence of a substance is actually greater in the case of a very little child than it is with a grown person. The virtue for the child of the mother's milk, for example, lies in the fact that there lives in it what was called in the archaic language of an earlier way of thought the “good mummy” in contrast to the “bad mummy” that lives in other products of excretion. The whole mother lives in the mother's milk. Mother's milk is permeated with forces that have, as it were, only changed their field of action within the organisation. For up to the time of birth, these forces are active in the region that belongs in the main to the system of metabolism and limbs, while after birth they are chiefly active in the region of the rhythmic system. Thus they migrate within the human organisation, moving up a stage higher. In doing so, the forces lose their I content, which was specifically active during the embryonic time, but still retain their astral content. If the same forces that work in the mother's milk were to rise a stage higher still—moving, that is, to the head—they would lose also their astral content and have active within them only the physical and etheric organisation. Hence the harmful effect upon the mother, if these forces do rise a stage higher and we have all the abnormal phenomena that can then show themselves in a nursing mother. In mother's milk we still have therefore astral formative forces that work spiritually; and we must realise what a responsibility rests upon us when the time comes to let the little child make the transition to receiving his nourishment directly for himself. The responsibility is particularly great for us today, since there is now no longer any consciousness of how the spiritual is active everywhere in the external world, and of how the plant, as it ascends from root up to flower and finally to fruit, becomes gradually more and more spiritual—in its own nature and also in its activity and influence. Taking first the root, we have there something that works least spiritually of all; in comparison with the rest of the plant, the root has a strongly physical and etheric relation to the environment. In the flower however begins a life which reaches out, in a kind of longing, to the astral. In a word, the plant spiritualises, as it grows upwards. Then we must carry our study a stage further, and enquire into the place of the root within the whole cosmic connection. Its part and place within the cosmos is expressed in the fact that the root has grown into the soil of the Earth, has embedded itself right into the light. The truth is that the root of the plant has grown into the soil in the same way as we have grown with our head into the free expanse of air and into the light. We can therefore say that here below  we have that which in man is of the head nature and has to do with perception; while here above we have the part of the plant that in man has to do with digestion, with nourishment. The upper part of the plant contains the spirituality that we long for in our metabolism-and-limbs system, and is on this account related to that system in us. One who is able with occult perception to regard first the mother's milk, and then the astral which hovers over the plant and for which the plant longs and yearns, can behold—not indeed a perfect similarity, but an extraordinarily close relationship between the astrality that comes from the mother with the mother's milk, and the astrality that comes from the cosmos and hovers over the blossoms of the plants. These things are said, not in order that you may possess them as theoretical knowledge, but in order that you may come to cherish the right feeling towards what is in a human being's environment and enters thence into the sphere of his deeds and actions. As you see, we shall have to take care that we find the right way to accustom the little child—gradually—to external nourishment, stimulating him with the fruiting part of the plant, fortifying his metabolic system with the flowering part, and coming to the help of what has to be done by the head by means of a gentle admixture of root substance in his food. The theoretical mastery of these relationships will serve merely to start you off in the right direction; what should then happen is that in the practice of life the knowledge of them flows into all your care for the child, not as theory but more in a spiritual way. In this connection we cannot but recognise how extraordinarily difficult it is in our day to “behold” a human being as he really is. Again and again, in every field of knowledge into which we enter, our attention is drawn away from that which is essential in man as man. Modern education and instruction is not calculated to enable us to see man in his true being. For it is a fact that in the course of the first half of the nineteenth century the power to behold what is essential in man died right away. Up to that time, and even still during that time, an idea was current which survives now only in certain words that have remained in use—lives on, here and there, so to speak, in the genius of language. We might describe this idea in the following way. Surveying the whole human race, we find it subject to all manner of diseases. We could, if we chose to be abstract, write these all down. We could take some plane surface and write upon it the names of the various illnesses in such a way as to make a kind of map of them. In one corner, for instance, we might write illnesses that are inter-related one with the other; in another corner, illnesses that are fatal. In short, we could classify them all so nicely as to produce in the end a regular chart or map, and then it would not be difficult to find the place on the map where a child with a particular organisation belonged. One could imagine how some special pre-disposition in regard to illness could be shown in a kind of diagram on transparent paper and then the name of the child be written in on the region of the map where he belonged. Let us suppose, then, that you regarded illnesses in this way and made such a map as I have described. In the first half of the nineteenth century people still had the idea that whenever the name of an illness had to be written in, they could always write in, for that illness, the name of some animal. They still believed that the animal kingdom inscribes into Nature all possible diseases, and that each single animal, rightly understood, signifies an illness. For the animal itself the illness is, so to speak, quite healthy. If however this same animal enters into man, so that a human being, instead of having the organisation that properly belongs to him, is organised on the pattern of that animal, then that human being is ill. It was not superstitious people alone who continued to hold such conceptions in the first half of the nineteenth century; this idea of the nature of disease in man was held, for example, by Hegel—and a very fruitful and productive idea it was. Think what a light can be thrown upon the nature and character of a particular human being if one can say: he “takes after” the lion, or the eagle, or the ox; or again, he gives evidence of being wrenched away in the direction of the spiritual—the spiritual works too powerfully in him. Or, let us say, carrying the idea a step further, suppose the ether body of a certain human being is too soft and flabby and shows obvious affinity to physical substance, then that would be for one an indication of a type of organisation that generally occurs only in the lower animal kingdom. These are fundamental conceptions of a kind that it is important for you to acquire. And now I would like to go on to speak of what you as educators must undertake for your own self-education. You can take your start from certain given meditations. A meditation that is particularly effective for a teacher is the one I gave here two days ago. Meditating upon it inwardly with the right orientation of heart and mind, it will in time bear fruit within you. For you will discover that as you are carried along in your feeling on the waves of an astral sea, borne hence away from the body, you will begin to find yourself in a world—you can liken it only to a world of gently surging billows—where you are given the possibility to see around you the very things that provide answers to your questions. But here, I must warn you that if you desire really to make your way through to the place where such things are possible, you must comply with the conditions—I do not mean merely knowing them in theory, I mean faithfully fulfilling in real earnest the conditions that are necessary for development on the path of meditation, and that are described in the book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and Its Attainment. [Now published by the Rudolf Steiner Press as Knowledge of Higher Worlds—how is it achieved? ] You will remember how mention is made there of egoism as a hindrance on the path of development—egoism in the sense that man centres his attention upon his own I, values his I too highly. What does it mean when we hold our I in such high esteem? We have, as you know, to begin with, our physical body, which derives from Saturn times and has been gradually formed and completed with such wonderful artistic power in four majestic stages of development. Then we have the etheric body, which has undergone three stages of development. And we have besides the astral body, which has undergone only two. These three members of man's being do not fall within the field of Earth consciousness; the I alone does so. Yet it is really no more than the semblance of the I that falls within the field of Earth consciousness; the true I can be seen only by looking back into an earlier incarnation. The I that we have now is in process of becoming; not until our next incarnation will it be a reality. The I is no more than a baby. And if we are able to see through what shows on the surface, then, when we look at someone who is sailing through life on the sea of his own egoism, we shall have before us the Imagination of a fond foster-mother or nurse, whose heart is filled with rapturous devotion to the baby in her arms. In her case the rapture is justified, for the child in her arms is other than herself; but we have a spectacle merely of egoism when we behold man fondling so tenderly the baby in him. And you can indeed see people going about like that today. If you were to paint a picture of them as they are in the astral, you would have to paint them carrying each his child on his arm. The Egyptians, when they moulded the scarab, could at least still show the I carried by the head organisation; but the man of our time carries his I, his Ego, in his arms, fondling it and caressing it tenderly. And now, if the teacher will constantly compare this picture with his own daily actions and conduct, once more he will be provided with a most fruitful theme for meditation. And he will find that he is guided into the state I described as swimming in a surging sea of spirit. Whether we are able to get in this realm the answers to our questions will depend upon whether we have in our soul the inner peace and quiet which we must seek to preserve in such moments. If someone complains that things are constantly happening that prevent him from meditating, the complaint will of itself afford a pretty sure indication as to whether or not he is in a fair way to make progress in this direction. For you will never find that one who is genuinely undergoing development will complain that this or that hinders him from meditating. In point of fact we are not really hindered by these things that seem to come in our way. On the contrary, it should be perfectly possible to carry out a most powerful meditation immediately before taking some decisive step, before doing a deed of cardinal importance—or, on the other hand, to carry out the meditation after the deed, in entire forgetfulness of what has been experienced in the performance of the deed. Everything depends, you see, upon having it in our power to wrest ourselves away from the one world and live for the time being completely within the other world; and whenever we want to summon up our inner spiritual powers, right at the very beginning must come the ability to do this. Watch for yourselves and observe the difference—first, when you approach a child more or less indifferently, and then again when you approach him with real love. As soon as ever you approach him with love, and cease to believe that you can do more with technical dodges than you can with love, at once your educating becomes effective, becomes a thing of power. And this is more than ever true when you are having to do with abnormal children. Wherever people have the right feeling about their activities, these activities do work together in the right way. Just as in the physical organism heart and kidneys must work together if the organism as a whole is to have unity, so must the Constituents work together for the great end they all have in view, while each of them fosters within itself that element in the whole for which it is in particular responsible. And anyone who then sets out to undertake some new task in the world, must bring what he is doing into co-ordination with what emanates from the Constituents. Suppose you have the intention of undertaking work with backward children. The first thing you have to do is to study and observe the pedagogy that is followed in the anthroposophical movement. That whole living stream of activity must flow into all that you do and undertake. For within this educational stream is contained that which can heal the typical human being, and enable him to take his place rightly in the world. And then you will find that the Medical Section is able to give you what you need in order that you may deepen this pedagogy and adapt it to the abnormality of the individual in question. If you set out in all earnestness to accomplish this, yon will soon realise that there can be no question of expecting simply to be told: This is good for this, that is good for that. No, what is wanted is a continual living intercourse and connection between your own work and all that is done and given in the educational and in the medical work of the [Dynamic] movement. No break in this living connection must ever be permitted. Egoism must not be allowed to creep in and assert itself in some special and individual activity; rather must there always be the longing on the part of each participant to take his right place within the work as a whole. Curative Eurythmy having come in to collaborate with Curative Education, the latter is thereby brought into relation also with the whole art of Eurythmy. Here too it should be evident that you must look for a living connection. This will mean that anyone who practises Curative Eurythmy must have gone some way towards mastering the fundamental principles of Eurythmy as an art. Curative Eurythmy has to grow out of a general knowledge of Speech Eurythmy and Tone Eurythmy—although the knowledge will not necessarily have been carried to the point of full artistic development. Nor must we lose sight of the importance before all else of human contacts. If Curative Eurythmy is being given, the one who is giving it must on no account omit to seek contact with the doctor. When Curative Eurythmy was first begun, the condition was laid down that it should not be given without consultation with the doctor. You see from all this how closely, how livingly interlinked the different activities have to be in Anthroposophy. It will thus be necessary to take care that the work you are initiating at Lauenstein—a work, let me say, that I regard as full of hope and promise—is carried on in entire harmony with the whole Anthroposophical Movement. You can rest assured that the Anthroposophical Movement is ready to foster and encourage any plans with which it has expressed agreement—naturally through the channels that have been provided in accordance with the Christmas Foundation Meeting. And conversely you should keep constantly in mind that whatever you, as a limb or member of the movement, accomplish—you do it for the strengthening of the whole Anthroposophical Movement, for the enhancement of its work and influence in the world. This then, my dear friends, is the message I would leave with you. Receive it into your hearts, as a message that comes verily from the heart; may it go with you, and may its impulse continue to work on into the future. If we who are in this spiritual movement are constantly thinking: how can this spiritual movement be made fruitful for practical life?—then will the world not fail to see that it is verily a movement that is alive. And so, my dear friends, let me wish you all strength and good guidance for the right working out of your will. [IMAGE REMOVED FROM PREVIEW] |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Building as a Setting for the Mystery Plays

02 Oct 1920, Dornach |

|---|

| What was spoken at that time out of truly shaped spiritual science oriented to anthroposophy is not the speech of fantasy or enthusiasm. It is the speech of spiritual research that can give an account of the nature of its research to the most exacting mathematician, as I said at another time. |

| 289. The Ideas Behind the Building of the Goetheanum: The Building as a Setting for the Mystery Plays

02 Oct 1920, Dornach |

|---|

Over a period of three hours I shall have the opportunity of speaking to you about the building idea of Dornach. In this first lecture, it is my task to characterize how this building idea emerged from the anthroposophically oriented spiritual movement, and then, over eight days and in a fortnight, to go into more detail about the style and the whole formal language of this our building, the framework and the external representative of our spiritual scientific movement. By speaking about the genesis of the Dornach building, I would like to perhaps touch on something personal by way of introduction. I spent the 1880s in Vienna. It was the Vienna in which the ideas were developed that could then be seen in the Votivkirche, in the Vienna City Hall, in the Hansen Building of the Austrian Parliament, in the museums, in the Burgtheater building, that is to say in those monumental buildings that were created in Vienna in the second half of the last century and which, to a certain extent, represent the most mature products of the architecture of the past era of human development. I would like to say that I heard the words of one of the architects involved in these buildings resound from the views from which these monumental buildings were created. When I was studying at the Vienna Technical University, Heinrich Ferstel, the architect of the Votivkirche, had just taken up his post as rector. In his inaugural address, he said something that I would like to say still echoes in my mind today, and it has echoed throughout my subsequent life. Ferstel said something at the time that summarized the most diverse views that had emerged in art at the time, especially in the art of architecture. He said: architectural styles are not invented, architectural styles are born out of the overall views, out of the overall development of the time and the emotional soulfulness of entire peoples and eras. On the one hand, such a sentence is extremely correct, and on the other hand, it is extremely inflammatory for the human mind. And anyone who has ever immersed themselves with artistic sensibility in the whole world of vision from which this remarkable Gothic structure of the Votive Church in Vienna, translated into miniature, was created by Ferstel himself, anyone who has felt the Vienna City Hall by Schmidt, anyone who has felt the Austrian Parliament in particular, which, through Hansen's genius, has achieved a certain freedom of style, at the time when this same view had not yet been spoiled by the hideous female figure that was later placed on the ramp. Those who had experienced the artistic heyday of Gottfried Semper's mature architecture at the Vienna Burgtheater could truly feel the background from which such an artistic view emerged as that of Heinrich Ferstel, which has just been characterized. In all that was built, one sees ripe fruits, but basically one sees only the renewal of the styles of past epochs of humanity. And I was able to feel this, I would like to say, inwardly inciting fact, for example, when I heard the lectures of the excellent esthete Joseph Bayer, who, out of the same spirit that Ferstel, Hansen, cathedral architect Schmidt, but especially Gottfried Semper, created with, tried to illustrate the forms of architectural art, the forms of ceramics, and so on. Such a fact, such a world of ideas, is inspiring for the human mind, I say this because perhaps, when faced with such an idea, “architectural styles are not invented, but born out of an overall spiritual life” in the human mind - when one sees: this view has achieved something magnificent and powerful, but from a mere renewal, from a renaissance of old architectural styles, old artistic perceptions, so to speak - because then the question arises before the soul: Are we perhaps such a barren time after all that we cannot give birth to something new in this sense from our overall view, from the scope of our world view? At the same time as all that could so richly fill the souls from these buildings when they immersed themselves in these views, from which the buildings arose, something else, though characteristic of the time, was concentrated in Vienna. In its soul body, Vienna had at that time also absorbed a certain height of precisely the newer medical progress. Skoda, Oppolzer and others represented a flowering of the development of medical science in the second half of the 19th century. At that time, especially if you lived among those who had to deal with such things, you could often hear a saying – and this saying also stayed with me: We live in a time in which medical nihilism has developed. This medical nihilism, which had emerged precisely in the heyday of pathology, actually culminated in the fact that the great physicians mainly studied those forms of disease that could be observed in their course merely through pathology, in which nature's healing process only needed to be helped along by all sorts of measures, but in which little could be done for the patient by taking remedies. Thus, precisely out of this medical school arose a disbelief in therapy, a skepticism about therapy. And when pathology had developed to its highest peak that it could reach at that time, people actually despaired of the possibility of real healing and, especially in initiated circles, spoke of medical nihilism. That is what one could feel. Our world view, where it was to prove fruitful in a certain area of practical life, led to nihilism and a certain powerlessness in the face of that practical life. Anyone with the ability to feel and perceive these things will, in the subsequent period of European civilization, be able to fully sense how, basically, those impulses, which on the one hand found expression in the fact that an architect as important as Heinrich Ferstel had to say, “Architectural styles are not invented, but are born out of the overall development of the time,” and yet still built in the sense of an old architectural style, on the other hand, expressed itself in the fact that in a practical area of life, people's views have led to nihilism. What developed from this in the period that followed was basically a continuation of what had been expressed in this way. Through the most diverse circumstances, seemingly, but probably through a necessary connection, I was confronted with the necessity of setting up impulses of a new spiritual life everywhere in the face of the appearance of what lay in the lines of development I have indicated. This new spiritual life would in turn draw from such original sources of human thought , human feeling and human will, as they repeatedly existed in the epochs of human development and as they proved fruitful in order to give rise to the artistic, the religious and the cognitive. If we want to feel in an even deeper way what the human mind was actually like at a time when, in art, only a kind of renaissance was living in the highest expressions of the artistic, and when, even in practical areas, views have led to a kind of nihilism When we delve into what was actually taking place in the soul and spirit during this time, we have to say that the spiritual matters that directly concern the human being, the scientific, and even to a high degree the religious life, had taken on an abstract, intellectual character. Man had come to cultivate less that which can arise from his entire human essence, his powers and impulses. In this most recent period, he had come to establish a mere head culture, a mere intellectualistic culture, to live in abstractions. This is something that occurs as a parallel phenomenon in the materialistic age: on the one hand, people believe that they can completely immerse themselves in the workings of material processes; but on the other hand, precisely because of this striving for immersion in a tendency towards abstraction, a tendency towards mere intellectualism, a tendency through which the urge to shape something that can directly reach into the full reality of existence fades from the most intimate affairs of the human soul. One withdraws into an abstract corner of one's soul life, leaving one's religious feelings to take place there. They withdraw into the closed rooms of the laboratory and the observatory, and devote themselves to specialized investigations in these fields, but in so doing they distance themselves from a truly living understanding of the totality of the world. One withdraws as a human being from real cooperation with practical life, and as a result one arrives at a closed intellectuality. And finally, everything that we see emerging in the fields of philosophy or world view in this period bears a distinctly abstract, a distinctly intellectual character. I believed that anthroposophically oriented spiritual science had to be placed in this current. It was not surprising that this spiritual science, when it was first placed in an intellectualist age, when it had to speak to people who, in the broadest sense, were fundamentally oriented towards intellectualist abstraction, initially had to appear as a worldview as if it itself had arisen only from abstraction, from mere thinking. And so it was that in our work for our anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, that phase arose which filled the first decade of the twentieth century and of which I would like to say: it was inevitable that our anthroposophically oriented world view should take on a certain intellectual character through the very nature of the people who were inclined towards it. It had to speak to people who, above all, believed that if you wanted to ascend to the spiritual and divine, you had to do so completely detached from the lower reality, you even had to arm yourself with a certain world-contempt, with a certain unreality of life. This was already an attitude that was alive in those who, out of their inclinations, had found their way into the current of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. And on the other hand, the world's judgment of this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science arose: Oh, they are dreamers, they are visionaries, they are people who are not relevant to practical life. This judgment arose - such things are very difficult to destroy - and still lives on today in most people who want to judge anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Of course, people saw that something different was alive in what appeared at that time as this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science than in their theories, in their world-view ideas. And since they regarded what they had sucked out of their bloodless abstractions from their materialistic orientation as the only spiritual reality to be attained by man himself, what the anthroposophically oriented spiritual science spoke to the world from completely different foundations seemed to them to be something fanciful, something fantastic. But a quite different phenomenon was involved. What was spoken at that time out of truly shaped spiritual science oriented to anthroposophy is not the speech of fantasy or enthusiasm. It is the speech of spiritual research that can give an account of the nature of its research to the most exacting mathematician, as I said at another time. But it is true: what has been spoken here out of spiritual realities sounded different from the bloodless world views of modern times. It sounded different, not because it was more abstract, or because it ascended to regions of the spirit more bloodless and frozen than those which have given rise to the theories developed out of the modern way of thinking, but it sounded different because it proceeded from spiritual realities, because it proceeded from those regions of man where one not only thinks, where one feels and wills, but does not feel and will in a dark way, not in the way that modern psychology considers to be the only one because it only knows this; not out of dark feeling, but out of feeling that is just as bright, as bright as the purest thinking itself. And the words were spoken out of a will that is suffused with a light that is striven for as the bright clarity of pure thoughts is striven for, and these thoughts are grasped when we seek to comprehend reality. Thus, in this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, there lived that which wanted to come from the whole person, which therefore also wanted to take hold of the whole person, to take hold of the thinking, feeling and willing human being. When one was able to speak in this way from the innermost being of the whole person, one often felt the inadequacy of even modern modes of expression. Anyone who has felt this way knows how to speak about it. One felt that modern times had also brought something into external language that leads words into abstract regions, and that speaking in the way language has now become itself invites abstraction. And one experiences, I would say, the inwardly tragic phenomenon of carrying within oneself something that one would like to express in broad content and sharp contours and developed with inner life, but that one is then rejected back to what modern language, which is coming out of an age of abstraction and is theoretical, alone knows how to say. And then one feels the urge for other means of expression. One feels the urge to express oneself more fully about what one actually carries within oneself than can be done through the theoretical debates in which modern humanity has been trained for three to four centuries, the theoretical debates that have shaped our concepts, our words, in which even our lyricists, our playwrights, our epic poets live more than they realize. One feels the necessity for a fuller, more vivid presentation. Out of such feelings, the need arose for me to say what was said in the first phase of our anthroposophical movement, which was clothed in more intellectual forms, through my mystery festival plays. I tried to present, in a theatrical way, in scenes and images that were to embrace the whole of human life, the physical, soul and spiritual life, what can be seen in the course of the world, what is contained in the course of the world as a partial solution to our great world riddles, but which can never be expressed in the abstract formulas into which the laws of nature can be expressed. This is how that which I then tried to depict in my mystery dramas came about. I had to resort to images to depict what comes from the whole human being. For only from the human being in his head comes what modern language has created for our science and our popular literature, and what today's people, if you listen to them, are able to understand. You have to touch the deeper sides of their minds if you want to speak to them what anthroposophical spiritual science actually has to say. This is how the need for these mystery dramas arose. These mystery dramas were first performed in Munich, in the surroundings, in the setting of ordinary theaters. Just as it literally blew apart the inside of the soul when one had to express the anthroposophically oriented spiritual science in the formulas of modern philosophy or world view, so it blew apart one's aesthetic sensation when one had to present in an ordinary theater, in an ordinary stage space, what was now to be depicted in a pictorial way: the spiritual content of the anthroposophical worldview and world feeling, of the anthroposophical world will. And when we worked in Munich on the theatrical presentation of these mystery plays in ordinary theaters, the idea arose to create a space of our own, to perform a building of our own, in which there would no longer be the sense of confinement that one in the manner just described for anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, but in which there is a framework that is itself the expression of what lives in anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. Therefore, this building was not created in the sense of an old architectural style, where one would have gone to any architect and had a house created for what anthroposophically oriented spiritual science is to work out, but rather it had to arise from the innermost being of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, because it did not merely work out of thinking and feeling, but out of the will itself, a structure had to arise out of this living existence of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science as a framework, which, as a style, as a formal language, gives the same as the spiritual-soul gives the spoken word of anthroposophically oriented spiritual science. A unity had to be created between the building as an art form and the living element present in this spiritual science. But if there is such a living element, if there is a living element that is not merely theoretical and abstract, if there is a truly living spiritual element, then it creates its own framework, because with such a spiritual element one lives within the creative forces of nature, within the creative forces of the soul, within the creative forces of the spiritual. And just as the shell of the nut is formed out of the same creative forces as the inside, which we then consume as a nut, just as the nutshell cannot be other than it is because it follows the laws the nut kernel comes into being, so this structure here in all its individual forms is such that it cannot be otherwise, because it is nothing other than a shell that has come into being, been formed, created according to the same laws as spiritual science itself. If I may express myself hyperbolically, it seems to me that at the end of my life I would not have been haunted by Heinrich Ferstel's thought that “architectural styles cannot be invented” if the truth contained in it had not been clearly reckoned with. Yes, architectural styles cannot be invented, they must arise out of an overall spiritual life. But if such a spiritual life as a whole exists, then it may dare, even if in a modest way, even with weak forces, to also gain an art style from the same spirituality from which this spirituality itself is created. I believe that I know better than anyone else what the faults of this building are, and I can assure you that I do not think immodestly about what has been created. I know everything I would do differently if I were to build such a structure again. I know how much this building is a beginning, how much of what is intended by it in the sense of its style may have to be realized quite differently. In any case, I do not want to think immodestly about this building. But with regard to what is intended by it, it may be pointed out how it wants to prove that architectural styles cannot be invented, but that they can be born if, instead of the nihilism of world view, a spiritual positivism is set, if, instead of the decadent decline of old world views, new sources of world view are sought. This building has therefore been created with a certain inner necessity. Just as feeling led us to present our world view in the mystery plays, as if feeling were to be taken into account in addition to thinking, so should the will, which is inherent in anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, first express itself artistically in this building. The fact that there is life in this spiritual science should, however, be shown in an equally modest way, just as a beginning – I always have to emphasize this – by the fact that we do not want to use this building to shut ourselves away and, as it were, strive for a higher world view as if it were a satisfaction of our inner soulful desires. No, in the next lectures on this building I will show you how all the building forms here live in such a way that they basically do not represent walls, but something artistically transparent. This is how the wall, which is designed here, differs from the walls that one is accustomed to in other architectural walls. The latter are final; one knows oneself inside a space that is limited in a certain way. Here, however, everything is shaped in such a way that, by looking at the frame, one can get the feeling, if one feels the thing in the right way, of how everything cancels itself out. Just as glass physically negates itself and becomes transparent, so the artistic forms of the walls are meant to negate themselves in order to become transparent; so painting and sculpture are meant to negate themselves in order to become transparent, so as not to lock up the soul in a room, but to lead the soul out into the world. And out of this tendency there also arose the impulse, still modest, which I call the social impulse and which in my book The Core of the Social Question should be presented to the world, not as a theory but as a call to action. Spiritual science could not remain with intellectuality. In its first phase it had to take human habits into account, had to speak to those people who were still educated entirely in abstract intellectualism. But it had to progress from thinking to feeling in order to present to the world what was to be expressed not only through the abstract word, but also through the dramatic play, the dramatic action, the dramatic image. But this spiritual science could not stop at mere feeling. It had to progress to the realm of will. It had to overcome and shape matter, it had to give form and life to matter. Therefore, a new framework, a new formal language, indeed a new architectural style, had to be sought for the mystery plays and for everything that wants to express itself through them, including the living anthroposophically oriented spiritual science itself. In order to affirm what lives as the deepest impulse in this anthroposophically oriented spiritual science, the social impulse also arose quite naturally in the time when adversity taught people to replace the tendency of decline with the tendency of ascent. We wanted to gain through this building, even through its style, that state of mind through which the human being goes out to experience all of social existence, goes out to be able to participate in the necessary social reconstruction of our time with living soul content. Thus, I believe, this structure can be seen as standing within what reveals itself as the deepest needs of our time, which in turn want to lead people out of mere abstractness and the materialism associated with it, out of mere thinking and into living feeling, and into active will. And we believe that in this way we also have what must be the substance, as it were, for what is so urgently demanded of us today, for what we know: If we humans are unable to accomplish it, the slide into barbarism will continue. A worldview that encompasses the whole person, the thinking, feeling and willing human being, must also be able to provide the state of mind that enables people to work together on what is a vital necessity of the present and the near future: social action. |

| 65. From Central European Intellectual Life: A Forgotten Quest for Spiritual Science Within the Development of German Thought

25 Feb 1916, Berlin |

|---|

| He says - Troxler's following words were written in 1835 -: "If it is highly gratifying that the newest philosophy, which we have long recognized as the one that founds all living religion and must reveal itself in every anthroposophy, thus in poetry as well as in history, is now making headway, it cannot be overlooked, that this idea cannot be a true fruit of speculation, and that the true personality or individuality of man must not be confused either with what it sets up as subjective spirit or finite ego, nor with what it confronts with as absolute spirit or absolute personality. In the 1830s, Troxler became aware of the idea of anthroposophy, a science that seeks to be a spiritual science based on human power in the truest sense of the word. Spiritual science can, if it is able to correctly understand the germs that come from the continuous flow of German intellectual life, say: Among Western peoples, for example, something comparable to spiritual science, something comparable to anthroposophy, can indeed arise; but there it will always arise in such a way that it runs alongside the continuous stream of the world view, alongside what is there science, and therefore very, very easily becomes a sect or a sectarianism. , but it will always arise in such a way that it runs alongside the continuous stream of world view, alongside what is science there, and therefore very, very easily tends towards sectarianism or dilettantism. |

| 65. From Central European Intellectual Life: A Forgotten Quest for Spiritual Science Within the Development of German Thought

25 Feb 1916, Berlin |

|---|