| 209. The Alphabet: An Expression of the Mystery of Man

18 Dec 1921, Dornach Translated by Violet E. Watkin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In short, what would be expressed by speaking the names of the alphabet consecutively, would not be the abstraction we have today when we say A, B, C, without any accompanying thoughts, but it would be the expression of the Mystery of Man and of how his roots are in the universe. When today, in various societies ‘the lost archetypal word’ is talked about, there is no recognition that it is actually contained in the sentence that comprises the names of the alphabet. |

| The history of Man should be studied in accordance with the development of his consciousness for then we can gain a feeling that consciousness must return to these matters. That is just what is attempted in anthroposophical Spiritual Science. There is no need to marvel that those who are accustomed to accept the recognized science of the day find nothing right in what I have written, for example, in Occult Science. |

| 209. The Alphabet: An Expression of the Mystery of Man

18 Dec 1921, Dornach Translated by Violet E. Watkin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

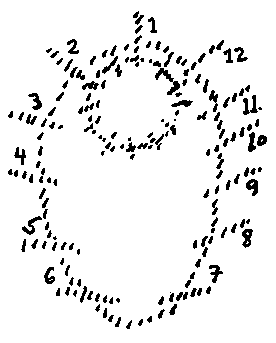

For some time we have been occupied with gaining a more accurate knowledge of Man's relation to the universe, and today we would like to supplement our past studies. If we consider how Man lives in the present period of his evolution—taking this period so widely that it encompasses not only what is historical but also in part the pre-historical—we must conclude that speech is a preeminent characteristic at this moment of the cosmic evolution of mankind. It is speech that elevates Man above the other kingdoms of nature. In the lectures last week, I mentioned that in the course of mankind's evolution, language, speech as a whole, has also undergone a development. I alluded to how, in very ancient times, speech was something that Man formed out of himself as his most primal ability; how, with the help of his organs of speech he was able to manifest the divine spiritual forces living within him. I also referred to how, in the transition from the Greek culture to the Roman-Latin culture, that is to say in the fourth Post-Atlantean period, the single sounds in language lose their names and, as in contemporary usage, merely have value as sounds. In Greek culture we still have a name for the first letter of the alphabet but in Latin it is just ‘A’. In passing from the Greek to the Latin culture something living in speech, something eminently concrete changes into abstraction. It might be said: as long as Man called the first letter of the alphabet ‘Alpha’, he experienced a certain amount of inspiration in it, but the moment he called it just ‘A’, the letters conformed to outer convention, to the prosaic aspects of life, replacing inspiration and inner experience. This constituted the actual transition from everything belonging to Greece to what is Roman-Latin—men of culture became estranged from the spiritual world of poetry and entered into the prose of life. The people of Rome were a sober, prosaic race, a race of jurists, who brought prose and jurisprudence into the culture of later years. What lived in the people of Greece developed within mankind more or less like a cultural dream which men approach through their own revelations when they have inner experiences and wish to give expression to them. It might be said that all poetry has in it something which makes it appear to Europeans as a daughter of Greece, whereas all jurisprudence, all outer compartmentalization, all the prose of life, suggest descent from the Roman-Latin people. I have previously called your attention to how a real understanding of the Alpha—Aleph in Hebrew—leads us to recognize in it the desire to express Man in a symbol. If one seeks the nearest modern words to convey the meaning of Alpha, these would be: ‘The one who experiences his own breathing’. In this name we have a direct reference to the Old Testament words: ‘And God formed Man ... and breathed into nostrils the breath of life’. What at that time was done with the breath, to make Man a Man of Earth, the being who had his Manhood imprinted on him by becoming the experiencer, the feeler of his own breathing, by receiving into himself consciousness of his breathing, is meant to be expressed in the first letter of the alphabet. And the name ‘Beta’ considered with an open mind, turning here to the Hebrew equivalent, represents something of the nature of a wrapping, a covering, a house. Thus, if we were to put our experience on uttering ‘Alpha, Beta,’ into modern language we could say: ‘Man in his house’. And we could go through the whole alphabet in this way, giving expression to a concept, a meaning, a truth about Man simply by saying the names of the letters of the alphabet one after another. A comprehensive sentence would be uttered giving expression to the Mystery of Man. This sentence would begin by our being shown Man in his building, in his temple. The following parts of the sentence would go on to express how Man conducts himself in his temple and how he relates to the cosmos. In short, what would be expressed by speaking the names of the alphabet consecutively, would not be the abstraction we have today when we say A, B, C, without any accompanying thoughts, but it would be the expression of the Mystery of Man and of how his roots are in the universe. When today, in various societies ‘the lost archetypal word’ is talked about, there is no recognition that it is actually contained in the sentence that comprises the names of the alphabet. Thus we can look back on a time in the evolution of humanity when Man, in repeating his alphabet, did not express what was related to external events, external needs, but what the divine spiritual mystery of his being brought to expression through his larynx and his speech organs. It might be said that what belongs to the alphabet was applied later to external objects, and forgotten was all that can be revealed to Man through his speech about the mystery of his soul and spirit. Man's original word of truth, his word of wisdom, was lost. Speech was poured out over the matter-of-factness of life. In speaking today, Man is no longer conscious that the original primordial sentence has been forgotten; the sentence through which the divine revealed its own being to him. He is no longer aware that the single words, the single sentences uttered today, represent the mere shreds of that primordial sentence. The poet, by avoiding the prose element in speech, and going back to the inner experience, the inner feeling, the inner formation of speech, attempts to return to its inspired archetypal element. One could perhaps say that every true poem, the humblest as well as the greatest, is an attempt to return to the word that has been lost, to retrace the steps from a life arranged in accordance with utility to times when cosmic being still revealed itself in the inner organism of speech. Today we distinguish the consonant from the vowel element in speech. I have spoken of how it would appear to Man if he were to dive beneath the threshold of his consciousness. In ordinary consciousness memories are reflected upwards or, in other words, thoughts are reflections of what is experienced between birth and death. Normally we do not penetrate Man's actual being beyond this recollection, this thought left behind in memory. From another point of view I have indicated how, beneath the threshold of consciousness, there lives what may be called a universal tragedy of mankind. This can also be described in the following way: When Man wakes up in the morning and his ego and astral body dive down into his etheric body and his physical body, he does not perceive these bodies from within outwards, what he perceives is something quite different. We can get an idea of this by means of a diagram.  Let us say that here we have the boundary between the conscious and the unconscious, red representing the conscious, blue the unconscious. If a person sees something belonging to the outer world or to himself, for instance, if with his own eye he sees another Man's eye, then the visible rays which go out of his eye into the other Man are thrown back, and he experiences it in his consciousness. What he also bears of his own being beneath the threshold of consciousness he experiences in his astral body and his ego, but not in the ordinary waking state. It remains unconscious and essentially forms the actual content of the etheric and the physical bodies. The etheric body is never recognized at all by ordinary consciousness; it recognizes only the external aspect of the physical body. As I have mentioned in the past, we must plunge beneath memory to perceive the primal source of evil in human beings, but then something else can also be perceived, namely, an aspect of Man's connection with the cosmos. We may, through appropriate meditation, succeed in penetrating the memory representations, as it were, to put aside what separates us inwardly from our etheric and physical bodies; if we then look down into the etheric body and the physical body so that we perceive what normally lies beneath the threshold of consciousness, we will hear something sounding within these bodies. And what sounds is the echo of the music of the spheres, which Man absorbed between death and new birth, during his descent out of the divine spiritual world into what is given to him through physical inheritance by parents and ancestors. In the etheric body and in the physical body there echoes the music of the spheres. In so far as it is of a vowel nature it echoes in the etheric body, and in the physical body in so far as it is of a consonant nature. It is indeed true that Man, as he goes forward in the life between death and a new birth, raises himself to the world of the higher hierarchies. We have learned how Man in the world of the Angels, the Archangels, the Archai, joins in with their life and lives within the realm of the hierarchies, as here we live among the beings of the mineral, plant and animal kingdoms. After this life between death and a new birth he descends once more to earthly life. And we have also learned how on his way down he first gathers to him the influences of the firmament of the fixed stars, represented in the signs of the Zodiac; then, as he descends further, he takes with him the influence of the moving planets. Now just picture to yourselves the Zodiac, the representation of the fixed stars. Man is exposed to their influence on descending from the life of soul and spirit into earthly life. If their effects are to be designated in accordance with their actual being we must say that they are cosmic music, they are consonants. And the forming of consonants in the physical body is the echo of what resounds from the single formations of the Zodiac, whereas the formation of vowels within the music of the spheres occurs through the movements of the planets in the cosmos. This is imprinted into the etheric body. Thus, in our physical body we unconsciously bear a reflection of the cosmic consonants, whereas in our etheric body we bear a reflection of the cosmic vowels. This remains, one might say, in the silence of the subconscious. But as the child develops, forces press upwards within the body and strengthen the speech organs; these are forces that, as reflections of the formative forces of the cosmos, build up the speech organs. The more interior speech organs are so formed out of Man's essential being that they can produce vowels, and the organs nearer to the periphery, the palate, the tongue, the lips and everything that contributes to the form of the physical body, are built up in such a way that consonants can be produced. While the child is learning to speak, something takes place in the upper part of his being, as a result of the activity of his lower part, which is a consequence of the formative forces taken up into the physical body, and also into the etheric body. (This is naturally not a material process but has to do with formative activity.) Thus when we speak, we bring to Manifestation what we might call an echo of the experience Man goes through with the cosmos in the life between death and a new birth during his descent out of the divine spiritual world. All the single letters of the alphabet are actually formed as images of what lives in the cosmos.  We can get an approximate idea of the signs of the Zodiac if we relate them to modern speech by setting up B, C, D, F, and so forth, as constellations of the Zodiac. You can follow them by feeling the revolution of the planets in H (ed.: ‘H’ like in him, her)—H is not actually a letter like the others, H imitates the rotational movement, the circling around. And the single planets in their revolutions are always the individual vowels which are placed in various ways in front of the consonants. If you imagine the vowel A to be placed in here (see diagram) you have the A in harmony with B and C, but in each vowel there is the H. You can trace it in speaking—AH, IH, EH. H is in each vowel. What does it signify that H is in each vowel? It signifies that the vowel is revolving in the cosmos. The vowel is not at rest, it circles around in the cosmos. And the circling, the moving, is expressed in the H hidden in each of the vowels. Consider, therefore, a vowel harmony expressed somewhere in speech: let us say I, O, U, A. (ed.: IH, OH, UH, AH in German) What is expressed by this? Something is expressed that is the cosmic working of four planets. Let us add one of the consonants to something like this—IOSUA—let us add this S in the middle of it, and this would mean that not only the forming of vowels within the planetary spheres is expressed, but also the effect that the planets connected with I, O, U, A, experience in their movement through the connection with the star sign S. Thus if a Man in the days of ancient civilization uttered the name of a God in vowels, a planetary mystery was expressed. The deed of a divine being within the planetary world was expressed in the name. Were a divine name expressed with a consonant in it, the deed of the divine being concerned reached in thought to the representative of the fixed star firmament—the Zodiac. When there was still an instinctive understanding of these things, in the time of atavistic clairvoyance, clairaudience, and so on, a connection with the cosmos was experienced in human speech. When speaking, Man felt himself within the cosmos. When the child learned to speak it was felt how what was experienced in the divine spiritual world before birth, or before conception, gradually evolved out of the being of the child. It may be said that if a Man could look through himself inwardly he would have to admit: I am an etheric body, in other words, I am the echo of cosmic vowels; I am a physical body, in other words, the echo of cosmic consonants. Because I stand here on the earth, there sounds through my being an echo of all that is said by the signs of the Zodiac; and the life of this echo is my physical body. An echo is formed of all that is said by the planetary spheres and this echo is my etheric body.

Nothing is said, my dear friends, by repeating that Man consists of physical body and etheric body. Those are no more than vague, indefinite words. If we want to speak in a real language, which can be learned from the mysteries of the cosmos, we would have to say: Man is constituted out of the echo of the heavens, of the fixed stars, of the echo of the planetary movements, of what is experienced of the echo of the planetary movements, and of what knowingly experiences the echo of the fixed star heavens. Then we would have expressed in real cosmic speech what is abstractly expressed by the words: Man is made up of physical body, etheric body, astral body and ego. We remain entirely in the abstract by saying: Man is composed first of physical body, secondly of etheric body, thirdly of astral body, fourthly of ego. But we pass into concrete cosmic speech if we say: Man consists of the echo of the Zodiac, of the echo of the planetary movements, of the experience of the impression of the planetary movements in thinking, feeling and willing, and in the perception of the echo of the Zodiac. The first is abstraction, the second reality. When you say ‘I’, what is that exactly? Now just imagine someone had planted trees in a beautifully artistic order. Each individual tree can be seen. However at a distance all the trees resolve into a single point. Take all the individual things—all that resounds from the Zodiac in the way of world consonants, then go far enough away: Everything that is formed as inward sound, in the most manifold way, is compressed within you to the single point ‘I’. It is an actual fact that this name which Man gives himself is really only an expression for what we perceive in the measureless spaces of the universe. Everywhere it is necessary to go back to what, as reflection, as echo, appears here upon earth. Thus, when the matter is seen in its reality, before Man's higher and inward experience, everything out of which Man builds himself up as a phenomenon, as pure experience, melts away. If we look upon Man and gradually learn to know his true nature, then his physical body actually ceases to be in the way it normally confronts us and otherwise stands before us, our vision widens and Man grows into the heavens of the fixed stars. The etheric body, too, ceases to be before us. Vision is extended, experience is extended, and we arrive at a perception of planetary life, for this human etheric body is a mere reflection of planetary life. Man standing before you is nothing but the phenomenon, the appearance, the image, of what goes on in the life of the planets. We think we have an individual human being in front of us, but this individual is a picture, on a certain spot, of the whole world. What then is the reason for the difference between an Asiatic and an American? The reason is that the starry heavens are portrayed at two different earthly points, just as we have various pictures of one and the same external fact. It is indeed true that when we observe Man the world begins to dawn upon us, and by such observation we are faced by the great mystery of the extent to which Man is an actual pictured microcosm of the reality of the macrocosm. Now of what does modern life consist? When we look back from these modern times upon mankind's life in primeval times, we still find an experience of Man's connection with the spiritual world in the instinctive consciousness of those ancient days. In the alphabet we can have a concrete experience of this. When, in primeval words, Man had to express the rich store of the divine in all its fullness, he uttered the letters of the alphabet. When he expressed the mystery of his own nature, in the way he learned about it in the Mysteries, then he voiced how he had descended through Saturn or Jupiter in their stellar relation to the Lion or the Virgin, in other words, how he had descended through the A or the I in their relation to the M or the L. He gave utterance to what he had then experienced of the music of the spheres, and that was his cosmic name. And in those ancient days men were instinctively aware that they brought a name down with them from the cosmos to the Earth. Since then Christian consciousness still preserves this primeval consciousness in an abstract way by consecrating individual days to the memory of saints, who, rightly understood, should give new life to the spiritual cosmos. By being born on a particular day of the year we should receive the name of the saint whose day it is on the calendar. What is meant to be expressed here in a more abstract way, was more concretely expressed in primeval times, when in the Mysteries the cosmic name of a person was found in accordance with what he experienced as he descended to earth, when with his being he created vowels with the planets and added them to the consonants of the Zodiac. The various groups of the human race had many names then, but these names were conceived in such a way that they harmonized with the universal all-embracing name. Considered from this point of view, what was the alphabet? It was what the heavens revealed through their fixed stars and through the planets moving across them. When the alphabet was spoken out of the original, instinctive, human wisdom it was astronomy that was expressed. What was spoken through the alphabet and what was taught in astronomy in those olden days was one and the same thing. The wisdom in the astronomy of those times was not presented in the same way as the learning contained in any branch of knowledge today, which is built up from single perceptions and concepts. It was conceived as a revelation that made itself felt on the surface of human experience, either in the form of an axiomatic truth or as part of an axiomatic truth. Thus a concrete experience was represented with a part of the primal wisdom. And there was something of quite a dim consciousness connected with the fact that, in the Middle Ages, those who were highly educated still had to learn grammar, rhetoric, dialectics, arithmetic, geometry, music and astronomy. In this ascent through the various spheres of learning lies a half conscious recognition of something, which in earlier days, existed in instinctive clarity. Today grammar has become very abstract. Going back into times of which history tells us nothing, but which, nevertheless, are still historical times, we find that grammar was not the abstract subject it is today but that men were led through grammar into the mystery of the individual letters. They learned that the secrets of the cosmos found expression in the letters. The single vowel was brought into connection with its planet, the single consonant with the single sign of the Zodiac; thus, through the letters of the alphabet, Man gained knowledge of the stars. Passing from grammar to rhetoric entailed the application of what lived in Man as active astronomy. And by rising to dialectics one came in thought to comprehending and working on what lived in Man out of astronomy. Arithmetic was not taught as the abstraction of today, but as the entity expressed in the mystery of numbers. Number itself was looked upon differently from how it is done today. I will give you a trifling instance of this. How does one picture 1, 2, 3 to oneself today? It is done by thinking of a pea, then of another pea, and this makes two; then another is added and there are three. It is a matter of adding one to another—piling them up. In olden days one did not count in this way. A start was made with a unit. And by splitting the unit into two parts one had 2. Thus 2 was not arrived at by adding one unit to another. It was not a putting together of units, but the two were contained in the one. Three was contained in the one in a different way—four again in a different way. The unit embraced all numbers and was the greatest. Today the unit is the smallest. Everything today is atomistically conceived. The unit is one member and the two is added to it, this is all imagined atomistically. The original idea was organic. There the unit is the greatest and the following numbers always appear as being smaller and are all contained in the unit. Here we come to quite different mysteries in the world of numbers. These mysteries in the world of numbers give the merest intimation that here we are not concerned with what merely lives in the hollow of Man's head. (I say the hollow of his head because I have often shown it really to be hollow from the spiritual point of view.) In the relations of number we can come to perceive the relations of the objectivity of the world. If we always just add one to one naturally this is something that has nothing to do with the facts. I have a piece of chalk. If beside it I place a second piece of chalk this has nothing to do with the first. The one is not concerned with the other. If, however, I presuppose that everything is a unit and now pass to the numbers contained in this unit, I get a two in a way that is a matter of some consequence. I have to break up the piece. I then get right into reality. Thus after being borne up in dialectics to grasping the thought of the astronomical, one reached still further into the cosmos with arithmetic and in a similar way with geometry. From geometry one got the feeling that the geometrical, thought concretely, was the music of the spheres. This is the difference between what holds good today and what once existed in the instinctive wisdom of primeval times. Take music today—the mathematical physicist reckons the pitch of a note, for example, reckons which pitch is at work in a melody. Then anyone who is musical is obliged to forget his music and enter the sphere of the abstract if, being a keen musician, he has not already run away from the mathematician. Man is led away from immediate experience into abstraction and this has very little to do with experience. In itself it is really interesting—if one has a mathematical bent—to press on from the musical into the sphere of acoustics, but one does not gain much in the way of musical experience. That someone today learns geometry and as he proceeds begins to experience forms as musical notes, that is to say, if he rises from the 5th to the 6th grade, and makes geometry sound musically, all this, as far as I know, does not enter the curriculum. But that was once the meaning of rising to the sixth part of what was to be learned—from geometry to music. And only then did the archetypal, underlying reality become an experience. The astronomy in the subconscious then became something that one consciously mastered as astronomy, as the highest and 7th member of the so-called Trivium and Quadrivium. The history of Man should be studied in accordance with the development of his consciousness for then we can gain a feeling that consciousness must return to these matters. That is just what is attempted in anthroposophical Spiritual Science. There is no need to marvel that those who are accustomed to accept the recognized science of the day find nothing right in what I have written, for example, in Occult Science. It is necessary, however, that Man should go back, in a fully conscious way, to the true reality which for a time had to recede into the background to enable Man to develop his freedom. Man would have been able ever more strongly to develop the consciousness of how necessary it is for him to stand within a divine cosmic world, had he not been cast out of this cosmos into the merely phenomenal, into pure appearance, so strongly indeed that the whole manifold splendor and majesty of the starry sky was condensed into the abstract ego. This was a necessary step in the struggle for freedom. For Man could develop his freedom only by pressing together quite indistinguishably into the single point of the ego something that, filled out by the whole of cosmic space, streamed through all time. But he would lose his being, he would no longer know or possess himself, no longer be active and act on his own initiative, were he not to reconquer the whole world from this single point of his ego, were he not to rise again from the abstract to the concrete. It is indeed important to understand how, in passing from the Greek to the Latin culture, abstraction took hold of European culture and thus resulted in the loss of the primeval word. It must be remembered that the Latin language was for a long time the language of the cultural elite. What persisted however, was a kind of desperate holding on to what this Latin language had actually already discarded. And what had been spoken in the Greek world then remained behind only in thought. Of the logos there remained logic—abstract thought. In the longing that a Man such as Goethe had for knowledge of the Greek culture, there lies something that may be expressed as follows: he longed for liberation from the abstraction of modern times, from the dry prose of Romanism. He wanted to reach the other daughter of the primeval wisdom of the world, what remained of all that stood for Greece.—We too must experience something of this kind if we wish to understand Goethe's intense yearning for the South. In modern school biographies we find nothing of all this. Only when in every individual thing there echoes a consciousness of Man being an expression of the whole cosmos, will the way be cleared for the forces needed for Man's progress, if civilization is not to decline into utter barbarism. |

| 273. The Problem of Faust: Faust and the “Mothers”

02 Nov 1917, Dornach Translated by George Adams Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| And now there is something to which we must be very much alive to if we are not to develop errornous opinions in this sphere. We, in anthroposophical circles, are seeking knowledge of the spiritual world. And everything said in the book “Knowledge of the Higher Worlds,” and other books of that nature, about the exercises for gaining admittance into those worlds, goes no farther than the means by which this knowledge may be obtained. |

| All this, even in the decadent new secret societies, is still among the things about which their conservative members will not speak. Goethe quite rightly judged it fit to give out knowledge of these things in the only way possible for him in that age. |

| 273. The Problem of Faust: Faust and the “Mothers”

02 Nov 1917, Dornach Translated by George Adams Rudolf Steiner |

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

My dear friends, What I am going to speak about this evening I should like to link on to the scenes we have just witnessed. And what can be said in this regard will fit in well with the whole course of our present considerations. Now I have often spoken here before about the importance of the ‘Mothers scene’ in the second part of Goethe's “Faust”; this scene, however, is of such a nature that one can repeatedly return to it because through its significant content, apart from the aesthetic value of the way in which it is introduced into the poem, it really contains a kind of culminating point of all that is spiritual in present day life. And if this ‘Mothers scene’ is allowed to work upon us, we shall well be able to say that it contains a very great deal of all that Goethe is wishing to indicate. It comes indeed out of Goethe's immediate soul experiences just as on the other it throws light on the significant, deep knowledge that we are obliged to recognise in him if we are to have any notion at all of what is meant by this scene where Faust is offered by Mephistopeles the possibility of descending to the Mothers. If we notice how, on Faust's reappearing and coming forth from the Mothers, the Astrologer refers to him as ‘priest’, and that Faust henceforward refers to himself as ‘priest’, we have to realise that there is something of deep import in this conversion of what Faust has been before into the priest. He has descended to the Mothers: he has gone through some kind of transformation. Leaving aside what one otherwise knows of the matter and what has been said by us in the course of years, we need reflect only upon how the Greek poets, in speaking of the Mysteries, refer to those who were initiated as having learnt to know the three world-Mothers—Rhea, Demeter and Proserpina. These three Mothers, their being, what they essentially are—all this was said to be learnt through direct perception by those initiated into the Mysteries in Greece. When we dwell upon the significant manner in which Goethe speaks in this scene, and also upon what takes place in the next, we shall no longer be in any doubt that in reality Faust has been led into regions, into kingdoms, that Goethe thought to be like that kingdom of the Mothers into which the initiate into the Greek Mysteries was led. By this we are shown how full of import Goethe's meaning is. And now remind yourselves of how the moment Mephistopheles mentions the word ‘Mothers’ Faust shudders, saying what is so full of meaning: “Mothers, Mothers! How strange that sounds!” And this is all introduced by Mephistopheles' words “It is with reluctance that I disclose the higher mystery.” Thus it is really a matter here of something hidden, a mystery, that Goethe, in this half secret way, found necessary to impart to the world in connection with the development of his Faust. We must now ask, and are able to do so on the basis of what we have been considering during these past years, what is supposed to happen to Faust in the moment that this higher mystery is unveiled before him? Into what world is he led? The world, into which he is led, the world he now enters, is the spiritual world immediately bordering on our physical one. Please remember clearly how I have already said that the crossing of the threshold into this world beyond the border must be approached in thought with great caution. As I said, this is because between the world that we observe with our senses and understand with our intellect, and that world from which the -physical one arises, there is a borderland as it were, a sphere where one may easily fall into deception and illusion when not sufficiently developed and prepared. It might be said that only in the world comprehended by the senses are there definite forms, definite outlines and boundaries. These do not exist in the world that is on other side of the border. This is something that it is very difficult to get the modern materialistic intellect to grasp—that in the moment that the threshold is passed everything is in constant movement, and the world of the senses rises out of all this continual movement like petrified forms. It is into this world so penetrated by movement—the imaginative world—that Faust is now transplanted; transplanted, however, by an external cause end not by gradual painstaking meditation. The cause comes from without. It is Mephistopheles, the force of evil working into the physical, who takes him over to the other world. And now there is something to which we must be very much alive to if we are not to develop errornous opinions in this sphere. We, in anthroposophical circles, are seeking knowledge of the spiritual world. And everything said in the book “Knowledge of the Higher Worlds,” and other books of that nature, about the exercises for gaining admittance into those worlds, goes no farther than the means by which this knowledge may be obtained. And here, as far as the present time and necessity are concerned in the giving out of these things to the world, it goes without saying that a halt must be made. Anyone wishing to advance beyond this, will come to the sphere that can be called the sphere of action in the supersensible world. This must be left to each individual. When he has once found the security of knowledge, he himself must undertake the action. But in what is meant to proceed between Faust and Mephistopheles this is not the case. Faust has actually to produce the departed Paris and Helen; therefore he does not only have to look into the spiritual world, he does not have to be an initiate only, but a magician, and must accomplish magical actions. It very clearly shown here in the way this scene is handled by Goethe how deeply familiar he was with certain hidden things in the human soul. The state of Faust's consciousness has to be changed. But at the same time he has to be given power to act out of supersensible impulses. In his connection with Faust, Mephistopheles, in his capacity as an ahrimanic force, belongs to our world of the senses, but as a supersensible being. He has been transplanted. He has no power over the worlds into which Faust is now to be transplanted. They really do not exist for him. Faust has to pass over into a different state of consciousness that perceives, beneath the foundation of our world of the senses, the never-ceasing weaving and living, surging and becoming, from which our sense-world is drawn. And Faust is to become acquainted with the forces that are there below. The ‘Mothers’ is a name not without significance for entering this world. Think of the connection of the word ‘Mothers’ with everything that is growing, becoming. In the attributes of the mother is the union of what is physical and material with what is not. Picture to yourselves the coming into physical existence of the human creature, his incarnation. You must picture a certain process that takes place through the interworking of the cosmos with the mother-principle, before the union of the male and female is consummated. The man who is about to become physical prepares himself beforehand in the female element. And we must now make a picture of this preparation that is confined to what goes on up to the moment when impregnation takes place—all therefore that takes place before impregnation. One has a quite wrong and materialistically biased notion if one imagines that there lie already formed in the woman all the forces that lead to the physical human embryo. That is not so. A working of the cosmic forces of the spheres takes place; into the woman work cosmic forces. The human embryo is always a result of cosmic activity. What is described in materialistic natural science as the germ-cell is in a certain measure produced out of the mother alone, but it is a counterpart of the great cosmic germ-cell. Let us hold this picture in mind—this becoming of the human germ-cell before impregnation, and let us ask ourselves what the Greeks looked for in their three mothers, Rhea, Demeter and Proserpina. In these three Mothers they saw a picture of those forces that, working down out of the cosmos, prepare the human cell. These forces however do not come from the part of the cosmos that belongs to the physical but to the supersensible. The Mothers Demeter, Rhea and Proserpina belong to the supersensible world. No wonder then that Faust has the feeling that an unknown kingdom is making its presence felt when the word ‘Mothers’ is spoken. Now think, my dear friends, what Faust really has to experience. If it were purely a matter of imaginative knowledge he would only need to be led into the normal state of meditation but, as has been said, he has to accomplish magical actions. For that it is necessary that the ordinary understanding, the ordinary intellect, with which men perceives the world of the senses, should cease to function. This intellect begins with incarnation into a physical body and ends with physical death. And it is this intellect in Faust that must be damped-down, clouded. He has to recognise that his intellect should cease to work. He must be taken up with his soul into a different region. This naturally should be understood as a significant factor in Faust is development. Now how does the matter appear from Mephistopheles' point of view? We must understand that there is danger in the fact that it is Mephistopheles who has to transform Faust's state of consciousness. And it gives the former himself a sense of uneasiness; in a certain way it becomes dangerous for him also. What then are the possibilities? They are twofold. Faust may acquire the new state of consciousness, learn to know the other world from which he can draw upon miraculous forces, and go to and fro from one world to the other, thus emancipating himself from Mephistopheles for he would then learn to know a world where the latter had no place. With that he would, become free from Mephistopheles. The other possibility would be that all might go very badly and Faust's intellect become clouded. Mephistopheles really puts himself in a very awkward situation. However, he has to do something. He has to give Faust the possibility of fulfilling his promise. He hopes that in some way or another the matter may arrange itself, for he wants neither of the alternatives. He does not want Faust to grow away from him nor does he wish him to be completely paralysed. I ask you to think over this and then to remember that it is all this that Goethe wants to indicate. In this scene of Faust he wishes to point out to the world that there is a spiritual kingdom, and that here he is showing the way in which man can relate himself to it. This is how things are connected. Since the beginning of the fifth post-Atlantean epoch the knowledge of these things has to a great extent been lost. I have told you that Goethe applied the knowledge he had personally received through great spiritual vision. The whole connection with the Mothers had entered into Goethe's soul when he read Plutarch. For Plutarch, the Roman story-teller whom Goethe read, speaks of the Mothers; and the following particular scene in Plutarch seems to have made a deep impression on Goethe. The Romans were at war with Carthage. Nicias is in favour of the Romans and wishes to seize the town of Engyon from the Carthaginians; he is therefore to be given over to the Carthaginians. So he feigns madness and runs through the streets crying “The Mothers—the Mothers are pursuing me!” From this you may see that in the time of which Plutarch writes this relation of the Mothers is brought into connection not with the normal understanding of the senses, but with a condition of man when this normal understanding is not present. It is beyond all doubt that what Goethe read in Plutarch stirred him to bring to expression in his “Faust” this idea of the Mothers. We also find mention in Plutarch of how the world has a triangular form. Now naturally these words ‘the world has a triangular form’ must not be taken in a heavy literal sense, for the spatial is but a symbol of what has neither time nor space. Since we live in space, spatial images must be used for what is nevertheless beyond image, time or space. Thus Plutarch gives the picture of a triangular world. This the whole world (see diagram). According to Plutarch in the centre of this triangle that is the world, the field of truth is found. Now out of this whole world Plutarch differentiates 183 worlds. 183 worlds, so he says, are in the whole circumference; they move around, and in the middle is this resting field of truth. This resting field of truth Plutarch describes as being separated by time from the surrounding 183 worlds—sixty on each of the three sides of the triangle and one at each angle makes 183. When, therefore, you take this imagination of Plutarch's, you have a world considered as consisting of three parts and in the cloud formation around it the 183 worlds welling and surging. That is at the same time the imagination for the “Mothers.” The number 183 is given by Plutarch.  Thus Plutarch, who in a certain sense held sway over the mystery wisdom, quoted the remarkable number 183. Let us now reckon how many worlds we get if we make a correct calculation up to the time of Plutarch's world. We must do so in the following way:

You see how when we apply our own way of reckoning and correctly calculate the separate divisions and the whole world, as they have made their evolutions up to the time of the fourth Post-Atlantean epoch when Plutarch lived, we can truthfully say that we get 183 worlds. Moreover, when we take our Earth upon which we are still evolving, and about which we cannot speak as of something completed, and when we look from this Earth to Saturn, Sun and Moon, there we find the “Mothers” that figure in another form in the Greek Mysteries under names Proserpina, Demeter and Rhea. For all the forces that are in Saturn, Sun and Moon are still working—working on into our own time. And those forces that are physical are but the shadow, the image, of what is spiritual. Everything physical is a mere picture of the spiritual. Consider this. If you do not take simply its outward, gross physical body, but its forces, its impulses, the Moon with its forces is at the same time in the Earth. The being of the Moon belongs to the being of the Earth. If you only want a realistic picture, you need to imagine it thus. Here is the Earth (see diagram); here you have a shaft connected with the Moon, and the Moon is turned round on it The shaft, however, has no physical existence. And all that is Moon-impulse is not only here in the Moon but this sphere penetrates the Earth.  We now ask whether these forces thus related to the Moon have a real existence anywhere. The Greeks looked upon them as mysterious, as very full of mystery. And our modern destiny is connected with the fact that these forces no longer retain their character as mysteries but have been made available for all. If we only concentrate on this one thing, on these forces that are connected with the Moon—then we have one of the Mothers. What is this one Mother? We shall best approach the answer to this question in the following way. In order to have a picture let us take any river—say the Rhine. What is the actual Rhine? On reflection—I have already spoken of this here—no one is really able to say what the Rhine is. It is called the Rhine. But what actually is it when we look into the matter? Is it the water? But in the next moment that has flowed away water has water has taken its place. It flows into the North Sea and other water and follows it, and that goes on continuously. Then what is the Rhine? Is the Rhine the trough, the bed? But no one believes that, for were the water not there no one would think of the bed as the Rhine. When you use the word ‘Rhine’ you are not referring to anything really there but to something in a constant state of metamorphosis—which, however, in certain sense does not change. If we picture this diagrammatically (see diagram) and assume that this is the Rhine and this the water that flows into it—well, now, this water is always evaporating and descending again.  If you consider that all rivers belong to one another, you will have to take into your calculations that the water evaporates and then falls again. To a certain extent the water that flows from its source down to its mouth always comes over again from the same reservoir in its rising and flowing down. The water completes its circulation here. But this water is divided up an extended over the surroundings; naturally you cannot follow the course of each drop. All the water that belongs to the earth, however, must be considered as a whole. The question of rejuvenating water does not come into consideration here, This is what happens where the water is concerned. Something the same happens with the air, and in yet another case. If you have a telegraph station here and here another, you know that it is only a wire that connects them. The other connection is set up by means of the whole earth, the current goes down into the earth. Here is the place where it is earthed. The whole goes through the earth.  Now if you make a picture of these two things you have the water, the running water that spreads itself out and sets itself in circulation; and if on the other hand you imagine the electricity spreading itself out down in the earth, then you have two things at different poles—two opposed realities. I am only indicating here, for you can piece it together yourselves out of any elementary book on physics. But we are led to the conclusion that in electricity you have under the earth the opposite of what goes on above the earth in the circulation of the water. What is there under the earth ruling as the being of electricity is Moon-impulse that has been left behind. It definitely does not belong to the earth. It is impulse remaining over from the Moon and was spoken of as such by the Greeks. And the Greeks still had knowledge of the relation between this force, distributed throughout the whole earth, and the reproductive forces. And there is this relation with the forces of growth and of increase. This was one of the ‘Mothers.’ Now you can imagine that all these premonitions of mighty connections did not arise before Faust merely as theories, but he felt himself obliged to seek out—to enter right into these impulses. Knowledge of this force was first of all given to those being initiated into the Greek Mysteries, this force together with the two other Mothers. The Greeks held all that was connected with electricity in secret in the Mysteries. And herein is where lies the decadence of the future of the earth—of which I have already spoken from another point of view—that these forces will be made public. One of these forces has already become so during the fifth post-Atlantean epoch—electricity. The others will be known about in the decadence of the sixth and seventh epochs. All this, even in the decadent new secret societies, is still among the things about which their conservative members will not speak. Goethe quite rightly judged it fit to give out knowledge of these things in the only way possible for him in that age. At the same time, however, you have one of the passages from which you can see how the great poet Goethe did not simply write as other poets write, but that each word of his bore its special impress and had its appointed place. Take for example the relation of the Mothers to electricity. Goethe belongs to those who treat of such things out of a thoroughly expert knowledge.

And Faust:

as if he had received an electric shock. This is written with intention—not haphazardly. In this scene nothing in connection with the matter in question is haphazard. Mephistopheles gives Faust a picture of what he is to find as the impulses of the 183 worlds. This picture works in Faust's soul as it should work, for Faust has gone through many things that bring him near the spiritual worlds. On that account these things already affect him. This is what I wanted chiefly to dwell upon, my dear friends, hew Goethe is wishing to set forth the most significant matters in this 'Mothers' scene. And by all this you can see from what worlds—what worlds of different consciousness—Faust has to bring Paris and Helen. Because Goethe is dealing with something of such supreme significance, what is spoken in this scene is actually different from what it appears at first sight. What Faust brings with him from these worlds—what I have already referred to—is recognised by the others who have assembled for a kind of drama. What makes them see it? It is half suggested: but by whom? By the Astrologer; and for that he has been chosen as astrologer. His words possess suggestive power. This is clearly expressed. These astrologers had an inherent art of influencing through suggestion, not the best kind of suggestion but an ahrimanic one. What then is our Astrologer actually doing as he stands among these courtiers, who really are not pictured as being particularly bright,—what is he doing? He is putting into them by suggestion what is necessary for all that has arisen as a special world through Faust's changed consciousness to become present in their minds. Remember what I showed you, what I once said to you, that nowadays it can be actually proved that spoken words produce a trembling in certain substances. You will surely find it in one or another of the lectures I have previously given here. I have wanted to remark upon this to show you how today the real nature of the conjuration scene can be demonstrated by experiment. Out of the smoke of the incense and the appropriate accompanying word is really developed what Faust brings for his consciousness out of quite another world. But this must be brought to the minds of the courtiers and made fully clear to them through the suggestive power of the Astrologer. What then does he do? He insinuates. He has the task of insinuating all this into the courtiers' ears. But insinuation is devil's rhetoric. So that through the words ‘insinuation is devil's rhetoric’ the devilish nature of the astrologer's art is brought home to us. That is the one meaning of the sentence. The other is connected with what actually happens on the stage. The devil sits in the prompter's box making his insinuations from there. Here you have a very prototype of a sentence signifying two different things. You have the purely scenic significance of the devil himself sitting, insinuation from the prompter's box, and the reality of this—the Astrologer insinuating to the Court. In the way he does this it is a devilish art. Thus, if you go to work in the right way, you will find many sentences here with double meaning. Goethe employs this ambiguity because he wishes to represent something that actually happened but did not do so purely in a course-grained, material fashion. It can be performed thus, but its reality has nothing to do with the physical. Goethe, however, wanted to portray something that actually happened and was moreover an impulse in modern history and played a part there. He did not intend that something of this kind was simply to be performed, he meant to show that these impulses had already flowed into modern history, were already there, were working. He wanted to represent a reality, and to say that, in what has been developing since the sixteenth century, the devil has definitely played a part. If you take this scene seriously you will got the two sides of the matter, and you will realise how Goethe knew that spiritual beings were playing into historic processes. And at the end you come to what I have so often indicated, namely, that Faust is not yet sufficiently developed to bring the matter to a conclusion, that he has not derived the possibility of entering other worlds from the right source but from the power of Mephistopheles. All this is what forms the last part of the scene. I shall add more to this tomorrow and bring our considerations further. But you have seen enough to know that in what Goethe wishes to say much of what we have been studying lately receives new light. |

| 159. The Mystery of Death: The Intimate Element of the Central European Culture and the Central European Striving

07 Mar 1915, Leipzig Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| When for reasons which were also mentioned yesterday in the public lecture6 our spiritual-scientific movement had to free itself from the specifically British direction of the Theosophical Society and when long ago as it were that happened beforehand in the spiritual realm what takes place now during the war—and preceded for good reasons,—I have discussed and explained the whole matter in those days on symptoms. |

| When I came to London the first time, I met one of the pundits of the theosophical society in those days, Mr. Mead.7 He had read the book which was immediately translated in many chapters into the English, and said that the whole theosophy would be contained in this book. |

| Mead: last private secretary of H. P. Blavatsky. He left the Theosophical Society later.8. Inner Nature of Man and Life Between Death and Rebirth, eight lectures (Vienna, 1914), Steiner's Collected Works volume 1539. |

| 159. The Mystery of Death: The Intimate Element of the Central European Culture and the Central European Striving

07 Mar 1915, Leipzig Translator Unknown Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

We live in grievous, destiny-burdened days. Only few souls wait with full confidence what these destiny-burdened days will bring to us earth people. Above all, the significance of that what expresses itself by the events of these days, does not speak with full strength in the souls. Some human souls attempt to experience the impulses more and more that spiritual science demands to be implanted into the cultural development. They should know being connected with their deepest feeling with that which, on one side, takes place around us so tremendously and, on the other side, so painfully. Something takes place that is matchless not only according to the way but also according to the degree within the conscious history of human development, that is deeply intervening and drastic in the whole life of the earth's development. One needs to imagine only what it means—and this is the case today with every human being of the European and also of many parts of the other earth population—to be in the centre of the course of such significant events. We have to feel that this is just a time which is not only suitable but also demands that the soul frees itself from merely living within the own self, and should attempt to experience the common fate of humankind. The human being can learn a lot in our present if he knows how to combine in the right way with the stream of the events. He frees himself from a lot of pettiness and egoism if he is able to do this. Such great events take place that almost anybody caring for himself ignores the destinies of the other human beings. In particular the population of Central Europe—which immense questions has it to put to itself about matters that it can learn basically only now! The human being of Central Europe can perceive how he is misunderstood, actually, how he is hated. And these misunderstandings, this hatred did not only erupt since the outbreak of the war, they have become perceptible since the outbreak of the war. Hence, the outbreak of the war and the course of the war can be even as it were that what draws attention of the Central European souls to that how they must feel isolated in a certain way more or less compared with the feeling of those people who stand on all sides around this Central European population really not with understanding emotions. If anybody could arouse deeper interests in the big events of life in the souls dedicating themselves to spiritual science—this would be so desirable, especially now—events that lead the soul from the ken of its ego to the large horizon of humankind! Then one were able to deepen the look, the whole attitude of the souls who recognise the encompassing forces, because they have taken up spiritual science in themselves, and release them from the interest in the narrow forces that deal only with the individual human being! If one hears the world talking today, in particular the world which is around us Central Europeans, if one reads which peculiar things there are written about the impulses which should have led to this war, then one has the feeling that humankind has lost the obligation to judge from larger viewpoints in our materialistic time, has lost so much that you may have the impression, as if people had generally learnt nothing, but for them history only began on the 25th July, 1914.1 It is as if people know nothing about that what has taken place in the interplay of forces of the earth population and what has led from this interplay of forces to the grievous involvements which caught fire from the flame of war, finally, and flared up. One talks hardly of the fact that one calls the encirclement by the previous English king who united the European powers round Central Europe, so that from this union of human forces around us, finally, nothing else could originate than that what has happened. One does not want to go further back as some years, at most decades and make conceptions how this has come what is now so destiny-burdened and painful around us. But the matters lie still much deeper. If one speaks of encirclement, one must say: what has taken place in the encirclement of the Central European powers in the last time, that is the last stage, the last step of an encirclement of Central Europe, which began long, long ago, in the year 860 A. D. At that time, when those human beings drove from the north of Europe who stood as Normans before Paris, a part of the strength, which should work in Europe, drove in the west of Europe into the Romance current which had flooded the west of Europe from the south. We have a current of human forces which pours forth from Rome via Italy and Sicily over Spain and through present-day France. The Norman population, which drives down from the north and stands before Paris in 860, was flooded and wrapped up by that which had come as a Romance current of olden times. That what is powerful in this current is due to the fact that the Norman population was wrapped up in it. What has originated, however, as something strange to the Central European culture in the West, is due to the Romance current. This Romance current did not stop in present-day France, but it proved to be powerful enough because of its dogmatically rationalistic kind, its tendency to the materialistic way of thinking to flood not only France but also the Anglo-Saxon countries. This happened when the Normans conquered Britain and brought with them that what they had taken up from the Romance current. Also the Romance element is in the British element which thereby faces the Central European being, actually, without understanding. The Norman element penetrated by the Romance element continued its train via the Greek coasts down to Constantinople. So that we see a current of Norman-Romance culture driving down from the European north to the west, encircling Central Europe like in a snake-form, stretching its tentacles as it were to Constantinople. We see the other train going down from the north to the east and penetrating the Slavic element. The first Norman trains were called “Ros” by the Finnish population which was widely propagated at that time in present-day Russia. “Ros” is the origin of this name. We see these northern people getting in the Slavic element, getting to Kiev and Constantinople at the same time. The circle is closed! On one side, the Norman forces drive down from the north to the west, becoming Romance, on the other side, to the east, becoming Slavic, and they meet from the east and from the west in Constantinople. In Central Europe that is enclosed like in a cultural basin what remained of the original Teutonic element, fertilised by the old Celtic element, which is working then in the most different nuances in the population, as German, as Dutch, as Scandinavian populations. Thus we recognise how old this encirclement is. Now in this Central Europe an intimate culture prepares itself, a culture which was never able to run like the culture had to run in the West or the culture in the East, but which had to run quite differently. If we compare the cultural development in Central Europe with that of the West, so we must say, in the West a culture developed—and this can be seen from the smallest and from the biggest feature of this culture—whose basic character is to be pursued from the British islands over France, Spain, to Sicily, to Italy and to Constantinople. There certain dogmatism developed as a characteristic of the culture, rationalism, a longing for dressing everything one gets in knowledge in plain rationalistic formulae. There developed a desire to see things as reason and sensuousness must see them. There developed the desire to simplify everything. Let us take a case which is obvious to us as supporters of spiritual science namely the arrangement of our human soul in three members: sentient soul, intellectual soul or mind-soul, and consciousness-soul. The human soul can be understood in reality only if one knows that it consists of these three members. Just as little as the light can be understood without recognising the colour nuances in their origin from the light, and without knowing that it is made up of the different colour nuances which we see in the rainbow, on one side the red yellow rays, on the other side the blue, green, violet ones, and if one cannot study the light as a physicist. Just as little somebody can study the human soul what is infinitely more important. For everybody should be a human being and everybody should know the soul. He, who does not feel in his soul that this soul lives in three members: sentient soul, intellectual soul or mind-soul, consciousness-soul, throws everything in the soul in a mess. We see the modern university psychologists getting everything of the soul in a mess, as well as somebody gets the colour nuances of the light simply in a mess. And they imagine themselves particularly learnt in their immense arrogance, in their scientific arrogance throwing everything together in the soul-life, while one can only really recognise the soul if one is able to know this threefolding of the soul actually. The sentient soul also is at first that what realises, as it were, the desires, the more feeling impulses, more that in the current earth existence what we can call the more sensuous aspect of the human being. Nevertheless, this sentient soul contains the eternal driving forces of the human nature in its deeper parts at the same time. These forces go through birth and death. The intellectual soul or mind-soul contains half the temporal and half the eternal. The consciousness-soul, as it is now, directs the human being preferably to the temporal. Hence, it is clear that the nation, who develops its folk-soul by means of the consciousness-soul, the British people, after a very nice remark of Goethe, has nothing of that what is meditative reflection, but it is directed to the practical, to the external competition. Perhaps, it is not bad at all to remember such matters, because those who have taken part in the German cultural life were not blind for them, but they expressed themselves always very clearly about that. Thus Goethe said to Eckermann2—it is long ago, but you can see that great Germans have seen the matters always in the true light—when once the conversation turned to the philosophers Hegel, Fichte, Kant and some others: yes, yes, while the Germans struggle to solve the deepest philosophical problems, the English are directed mainly to the practical aspects and only to them. They lack any sense of reflection. And even if they—so said Goethe—make declamations about morality mainly consisting of the liberation of slaves, one has to ask: which is “the real object?”—At another occasion, Goethe wrote3 that a remark of Walter Scott expresses more than many books. For even Walter Scott admitted once that it was more important than the liberation of nations, even if the English had taken part in the battles against Napoleon, “to see a British object before themselves.” A German philologist succeeded—and what does the diligence of German philologists not manage—in finding the passage in nine thick volumes of Napoleon's biography by Walter Scott to which Goethe has alluded at that time. Indeed, there you find, admitted by Walter Scott, that the Britons took part in the battles against Napoleon, however, they desired to attain a British advantage. He himself expresses it “to secure the British object.”—It is a remark of the Englishman himself, one only had to search for it. These matters are interesting to extend your ken somewhat today. You have to know, I said, that the human soul consists of these three members, properly speaking that the human self works by these three soul nuances like the light by the different colour nuances, mainly in the mineral, plant, and animal kingdoms. Then one will find out that the human being, while he has these three soul nuances, can and must assign each of these soul nuances to a great ideal in the course of human progress. Each of these ideals corresponds to a soul nuance not to the whole soul. Only if people can be induced by spiritual science to assign the corresponding ideals to the single soul members, will the real ideal of human welfare and of the harmonious living together of human beings on earth come into being. Because the human being has to aim at another ideal for his sentient soul, for that which he realises as it were in the physical plane, at another soul ideal for that what he realises in the intellectual soul or mind-soul, and again another ideal in his consciousness-soul. He improves a soul member through one of these ideals; the other soul members are improved through the others. If one develops the soul member in particular through brotherliness of the human beings on earth, one has to develop the other one through freedom, the third through equality. Each of these three ideals refers to a soul member. In the west of Europe everything got muddled, and it was simplified by the rationalists, by that rationalism, which wants to have everything in plain formulae, in plain dogmas, which wants to have everything clearly to mind. The whole human soul was taken by this dogmatism simply as one, and one spoke of liberty, fraternity, equality. We see that there is a fundamental attitude of rationalising civilisation in the West. We could verify that in details. For example, just highly educated French can mock that I used five-footed iambi in my mystery dramas4 but no rhymes. The French mind cannot understand that the internal driving force of the language does not need the rhyme at this level. The French mind strives for systematisation, for that what forms an external framework, and it says: one cannot make verses without rhyme. However, this also applies to the exterior life, to everything. In the West, one wants to arrange, to systematise, and to nicely tin everything. Think only what a dreadful matter it was, when in the beginning of our spiritual-scientific striving many of our friends were still influenced by the English theosophical direction. In every branch you could find all possible systems written down on maps, boards et cetera, on top, nicely arranged: atma, buddhi, manas, then all possible matters in detail which one systematises and tins that way. Imagine how one has bent under the yoke of this dogmatism and how difficult it was to set the methods of internal development to their place, which we must have in Central Europe, that one thing ensues from the other, that concepts advance in the internal experience. One does not need systematising, these mnemonic aids which wrap up everything in certain formulae. Which hard work was it to show that one matter merges into another, that you have to arrange matters sequentially and lively. I could expand this account to all branches of life; however, we would have to stay together for days. We find that in the West as one part of the current which encircled Central Europe. If we go to the East, then we must say: there we deal with a longing which just presents the opposite, with the longing to let disappear everything still in a fog of lacks of clarity in a primitive, elementary mysticism, in something that does not stand to express itself directly in clear ideas and clear words. We really have two snakes—the symbol is absolutely appropriate,—one of them extends from the north to southeast, the other from the north to southwest, and both meet in Constantinople. In the centre that is enclosed what we can call the intimate Central European spiritual current, where the head can never be separated from the heart, thinking from feeling, if it appears in its original quality. One does not completely notice that in our spiritual science even today, because one has to strive, even if not for a conceptual system, but for concepts of development. One does not yet notice that everything that is aimed at is not only a beholding with the head. However, the heart and the whole soul is combined with everything, always the heart is flowed through, while the head, for example, describes the transitions from Saturn to the Sun, from the Sun to the Moon, from the Moon to the earth et cetera. Everywhere the heart takes part in the portrayal; and one can be touched there in the deepest that one ascends with all heart-feeling to the top heights and dives in the deepest depths and can ascend again. One does not notice this even today that that what is described only apparently in concepts one has to put one's heart and soul in it at the same time if it should correspond to the Central European cultural life. This intimate element of the Central European culture is capable of the spiritual not without ideal, not to think the ideal any more without the spiritual. Recognising the spirit and combining it intimately with the soul characterises the Central European being most intensely. Hence, this Central European being can use that what descends to the deepest depths of the sensory view and the sensory sensation to become the symbol for the loftiest. It is deeply typical that Goethe, after he had let go through his mind the life of the typical human being, the life of Faust, closed his poem with the words:

and the last words are: