| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): Fifth Lecture

31 May 1905, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| It is therefore half of an octahedron because it intersects half of the faces of the octahedron. It is not the case that you cut the octahedron in half. If you bring the other four faces of the octahedron to the cut, the result is also a tetrahedron, which together with the first tetrahedron has the octahedron as a common intersection. |

| But this applies only to the cube. The rhombic dodecahedron, cut in half, also gives a different spatial structure. Figure 38 Now let us take the relation of the octahedron to the tetrahedron. |

| For this purpose, let us take a tetrahedron, which we cut off at one vertex (Figure 38). We continue this process until the cut surfaces meet at the edges of the tetrahedron; then what remains is the indicated octahedron. |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): Fifth Lecture

31 May 1905, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Last time, we tried to get an idea of a four-dimensional space. To visualize it, we reduced it to a three-dimensional one. First, we started by transforming a three-dimensional space into a two-dimensional one. We used colors instead of dimensions. We formed the idea in such a way that a cube appeared in three colors along the three dimensions. Then we laid the boundaries of a cube on the plane, which resulted in six squares in different colors. Through the diversity of colors on the individual sides, we obtained the three different dimensions in two-dimensional space. We had three colors, and with that we had represented the three dimensions. We then imagined that we were passing a square cube into the third dimension, as if we were passing it through a colored fog and it reappeared on the other side. We imagined that we had pass squares, so that the square cubes move through these squares and are thereby tinged [with the color of the pass square]. This is how we tried to imagine the [three-dimensional] cube [by means of a two-dimensional color representation]. [For the one-dimensional representation of the] surfaces, we thus have two boundary colors and [for the two-dimensional representation of the] cube, three colors. [To represent a four-dimensional spatial structure in three-dimensional space, we must] then add a fourth boundary color. Now we have to imagine in the same way that a cube, which, analogous to our square, has two different colors as boundary sides, has three different colors in its boundary surfaces. And finally, each cube moves through another cube that has the corresponding fourth color. In doing so, we let it disappear into the fourth color dimension. So, according to Hinton's analogy, we let the respective boundary cubes pass through the new [fourth] color, which then reappears on the other side, emerging in their [original] own color.  Now I will give you another analogy and first reduce the three dimensions back to two, so that we will then be able to reduce four dimensions to three. To do this, we have to imagine the following. The cube can be put together at its boundary surfaces from its six boundary squares; but instead of doing it in succession, as we did recently, it will now be done in a different way. I will also draw this figure (Figure 31). You see, we have now spread out the cube in two systems, each of which lies in the plane and consists of three squares. Now we have to be clear about how these different areas will lie when we actually put the cube together. I ask you to consider the following. If I now want to reassemble the cube from these six squares, I have to place the two sections on top of each other so that square 6 comes to rest on square 5. When square 5 is placed at the bottom, I have to fold up squares 1 and 2, while folding down squares 3 and 4 (Figure 32). In doing so, we get certain corresponding lines that overlap. The lines marked in the figure with the same color [here in the same line quality and in the same number of lines] will coincide. What lies here in the plane, in two-dimensional space, coincides to a certain extent when I move into three-dimensional space.  The square consists of four sides, the cube of six squares, and the four-dimensional area would then have to consist of eight cubes.? We call this four-dimensional area a tessaract [after Hinton]. Now, the point is that these eight cubes cannot simply be reassembled into a cube, but that one of them should always pass through the fourth dimension in the appropriate way. If I now want to do the same with the tessaract as I just did with the cube, I have to follow the same law. The point is to find analogies of the three-dimensional to the two-dimensional and then of the four-dimensional to the three-dimensional. Just as I obtained two systems of [three squares each] here, the same thing happens with the tessaract with [two systems of four cubes each] when I fold a four-dimensional tessaract into three-dimensional space. The system of eight cubes is very ingeniously devised. This structure will then look like this (Figure 33). Each time, these four cubes in three-dimensional space are to be taken exactly as these squares in two-dimensional space.  You just have to look carefully at what I have done here. When the cube was folded into two-dimensional space, a system of six squares resulted; when the corresponding procedure is carried out on the tessaract, we obtain a system of eight cubes (Figure 34). We have transferred the observation from three-dimensional space to four-dimensional space. [Folding up and joining the squares in three-dimensional space corresponds to folding up and joining the cubes in four-dimensional space.] In the case of the folded-down cube, [in the two-dimensional plane] different corresponding lines were obtained, which coincided when it was folded up again later. The same occurs with the surfaces of our individual cubes of the tessaract. [When the tessaract is folded down in three-dimensional space, corresponding surfaces appear on the corresponding cubes.] So, for example, in the case of the tessaract, the upper horizontal surface of  cube 1—by observing [mediation] the fourth dimension—with the front face of cube 5. In the same way, the right face of cube 1 coincides with the front square of cube 4, and likewise the left square of cube 1 with the front square of cube 3 [as well as the lower square of cube 1 with the front square of cube 6]. The same applies to the other cube surfaces. The remaining cube, 7, is enclosed by the other six. You see that here again we are concerned with finding analogies between the third and fourth dimensions. Just as a fifth square enclosed by four squares remains invisible to the being that can only see in two dimensions, as we saw in the corresponding figure of the previous lecture (Figure 29), so it is the case here with the seventh cube: it remains hidden from the three-dimensional eye. Corresponding to this seventh cube in the tessaract is an eighth cube, which, since we have a four-dimensional body here, lies as a counterpart to the seventh in the fourth dimension. All analogies lead us to prepare for the fourth dimension. Nothing forces us to add the other dimensions to the usual dimensions [within the mere spatial view]. Following Hinton, we could also think of colors here and think of cubes put together in such a way that the corresponding colors come together. It is hardly possible in any other way [than by such analogies] to give a description of how to think of a four-dimensional entity. Now I would like to mention another way [of representing four-dimensional bodies in three-dimensional space], which may also give you a better understanding of what we are actually dealing with here. This is an octahedron bounded by eight triangles, with the sides meeting at obtuse angles (Figure 35).  If you visualize this structure here, I ask you to follow the following procedure with me in your mind. You see, here one surface is always intersected by another. Here, for example, in AB, two side surfaces meet, and here in EB, two meet. The entire difference between an octahedron and a cube lies in the angle of intersection of the side surfaces. If surfaces intersect as they do in a cube [at right angles], a cube is formed. But if they intersect as they do here [obtuse], then an octahedron is formed. The point is that we can have surfaces intersect at the most diverse angles, and then we get the most diverse spatial structures."  Now imagine that we could also make the same faces of the octahedron intersect in a different way. Imagine this face here, for example AEB, continued on all sides, and this lower one here, BCF, also (Figure 36). Then likewise the ADF and EDC lying backwards. Then these faces must also intersect, and in fact they intersect here in a doubly symmetrical way. If you extend these surfaces in this way, [four of the original boundary surfaces] are no longer needed: ABF, EBC and, towards the back, EAD and DCF. So of the eight surfaces, four remain. And the four that remain give this tetrahedron, which is also called half of an octahedron. It is therefore half of an octahedron because it intersects half of the faces of the octahedron. It is not the case that you cut the octahedron in half. If you bring the other four faces of the octahedron to the cut, the result is also a tetrahedron, which together with the first tetrahedron has the octahedron as a common intersection. In stereometry [geometric crystallography], it is not the part that is halved that is called the half, but the one that is created by halving the [number of] faces. With the octahedron, this is quite easy to imagine. If you imagine halving the cube in the same way, that is, if you allow one face to intersect with the corresponding other face, you will always get a cube. Half of a cube is a cube again. I would like to draw an important conclusion from this, but first I would like to use something else to help me. Here I have a rhombic dodecahedron (Figure 37). You can see that the surfaces adjoin each other at certain angles. At the same time, we can see a system of four wires, which I would like to call axial wires, and which run in opposite directions to each other [i.e. connect certain opposite corners of the rhombic dodecahedron, and are therefore diagonals]. These wires now represent a system of axes in a similar way to the way in which you imagined a system of axes on the cube. You get the cube when you create sections in a system of three perpendicular axes by introducing blockages in each of these axes.  If the axes are made to intersect at other angles, a different spatial figure is obtained. The rhombic dodecahedron has axes which intersect at angles other than right angles. The cube reflects itself in half. But this applies only to the cube. The rhombic dodecahedron, cut in half, also gives a different spatial structure.  Now let us take the relation of the octahedron to the tetrahedron. And I will tell you what is meant by this. This becomes clear when we gradually let the octahedron merge into the tetrahedron. For this purpose, let us take a tetrahedron, which we cut off at one vertex (Figure 38). We continue this process until the cut surfaces meet at the edges of the tetrahedron; then what remains is the indicated octahedron. In this way we obtain an eight-sided figure from a three-dimensional figure bounded by four surfaces, provided we cut off the corners at corresponding angles.  What I have done here with the tetrahedron, you cannot do with the cube. The cube has very special properties, namely that it is the counterpart of three-dimensional space. Imagine the entire universe structured in such a way that it has three perpendicular axes. If you then imagine surfaces perpendicular to these three axes, you will, under all circumstances, get a cube (Figure 39). That is why, when we speak of the cube, we mean the theoretical cube, which is the counterpart of three-dimensional space. Just as the tetrahedron is the counterpart of the octahedron when I make the sides of the octahedron into certain sections, so the single cube is the counterpart of the whole of space.” If you think of the whole of space as positive, the cube is negative. The cube is the polar opposite of the whole of space. Space has in the physical cube its actually corresponding structure. Now suppose I would not limit the [three-dimensional] space by two-dimensional planes, but I would limit it in such a way that I would have it limited by six spheres [thus by three-dimensional figures]. I first define two-dimensional space by having four circles that go inside each other [i.e., two-dimensional shapes]. You can now imagine that these four circles are getting bigger and bigger [as the radius gets longer and longer and the center point moves further and further away]; then, over time, they will all merge into a straight line (Figure 40). You then get four intersecting lines, and instead of the four circles, a square.  Now imagine that the circles are spheres, and that there are six of them, forming a kind of mulberry (Figure 41). If you imagine the spheres in the same way as the circles, that they get larger and larger in diameter, then these six spheres will ultimately become the boundary surfaces of a cube, just as the four circles became the boundary lines of a square. The cube has now been created from the fact that we had six spheres that have become flat. So the cube is nothing more than a special case of six interlocking spheres – just as the square is nothing more than a special case of four interlocking circles.  If you are clear in your mind about how to imagine these six spheres, that they correspond to our earlier squares when brought into the plane, and if you imagine an absolutely round shape passing into a straight one, you will get the simplest spatial form. The cube can be imagined as the flattening of six spheres pushed into each other. You can say of a point on a circle that it must pass through the second dimension if it is to come to another point on the circle. But if you have made the circle so large that it forms a straight line, then every point on the circle can come to every other point on the circle through the first dimension. We are considering a square bounded by figures, each of which has two dimensions. As long as each of the four boundary figures is a circle, it is therefore two-dimensional. Each boundary figure, when it has become a straight line, is one-dimensional. Each boundary surface of a cube is formed from a three-dimensional structure in such a way that each of the six boundary spheres has one dimension removed. Such a boundary surface has therefore been created by the third dimension being reduced to two, so to speak bent back. It has therefore lost a dimension. The second dimension was created by losing the dimension of depth. One could therefore imagine that each spatial dimension was created by losing a corresponding higher dimension. Just as we obtain a three-dimensional figure with two-dimensional boundaries when we reduce three-dimensional boundary figures to two-dimensional ones, so you must conclude that when we look at three-dimensional space, we have to think of each direction as being flattened out, and indeed flattened out from an infinite circle; so that if you could progress in one direction, you would come back from the other. Thus, each [ordinary] spatial dimension has come about through the loss of the corresponding other [dimension]. In our three-dimensional space, there is a three-axis system. These are three perpendicular axes that have lost the corresponding other dimensions and have thus become flat. So you get three-dimensional space when you straighten each of the [three] axis directions. If you proceed in reverse, each spatial part could become curved again. Then the following series of thoughts would arise: If you curve the one-dimensional structure, you get a two-dimensional one; by curving the two-dimensional structure, you get a three-dimensional one. If you finally curve a three-dimensional structure, you get a four-dimensional structure, so that the four-dimensional can also be imagined as a three-dimensional structure curved on itself.* And with that, I come from the dead to the living. Through this bending, you can find the transition from the dead to the living. Four-dimensional space is so specialized [at the transition into three dimensions] that it has become flat. Death is [for human consciousness] nothing more than the bending of the three-dimensional into the four-dimensional. [For the physical body taken by itself, it is the other way around: death is a flattening of the four-dimensional into the three-dimensional.] |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): Sixth Lecture

07 Jun 1905, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Such a change can indeed be made, and it corresponds exactly to the change that a three-dimensional being undergoes when it passes into the fourth dimension, when it develops through time. If you cut a four-dimensional being at any point, you take away the fourth dimension, you destroy it. If you do that to a plant, you do exactly the same thing as if you were to make a cast of the plant, a plaster cast. |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): Sixth Lecture

07 Jun 1905, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

I would like to conclude the lectures on the fourth spatial dimension today if possible, although I would like to demonstrate a complicated system in more detail today. I would have to show you many more models after Hinton; therefore, I can only refer you to the three detailed and spirited books.” Those who do not have the will to form a picture through analogies in the way we have heard it in the past lectures cannot, of course, form a picture of four-dimensional space. It involves a new way of forming thoughts. I will try to give you a true representation [parallel projection] of the tessaract. You know that in two-dimensional space we had the square, which is bounded by four sides. This is the three-dimensional cube, which is bounded by six squares (Figure 42).  In four-dimensional space, we have the tessaract. A tessaract is bounded by eight cubes. The projection of a tessaract [in three-dimensional space] therefore consists of eight interlocking cubes. We have seen how the [corresponding eight] cubes can be intertwined in three-dimensional space. Today I will show you a [different] way of projecting the tessaract. You can imagine that the cube, when held up to the light, throws a shadow on the blackboard. We can mark this shadow figure with chalk (Figure 43). You see that a hexagon is obtained. Now imagine this cube transparent, and you will observe that in the hexagonal figure the three front sides of the cube and the three rear sides of the cube fall into the same plane.  In order to get a projection that we can apply to the tessaract, I would ask you to imagine that the cube is standing in front of you in such a way that the front point A covers the rear point C. If you imagine the third dimension, all this would give you a hexagonal shadow again. I will draw the figure for you (Figure 44).  If you imagine the cube like this, you would see the three front surfaces here; the other surfaces would be behind them. The surfaces of the cube appear foreshortened and the angles are no longer right angles. This is how you see the cube depicted so that the surfaces form a regular hexagon. Thus, we have obtained a representation of a three-dimensional cube in two-dimensional space. Since the edges are shortened and the angles are changed by the projection, we must therefore imagine the [projection of the] six boundary squares of the cube as shifted squares, as rhombi. The same story that I did with a three-dimensional cube that I projected into the plane, we want to do this procedure with a four-dimensional spatial object, which we therefore have to place in three-dimensional space. We must therefore bring the structure composed of eight cubes, the tessaract, into the third dimension [by parallel projection]. With the cube, we obtained three visible and three invisible edges, all of which enter into the space and in reality do not lie within the [projection] surface. Now imagine a cube shifted in such a way that it becomes a rhombicuboctahedron.” Take eight of these figures, and you have the possibility of combining the eight [boundary] cubes of the tessaract in such a way that, when pushed together, they form the eight (doubly covered) rhombicuboctahedra of this spatial figure (Figure 45).  Now you have one more axis here [than in the three-dimensional cube]. Accordingly, a four-dimensional spatial structure naturally has four axes. So if we push it together, four axes still remain. There are eight [pushed together] cubes in this projection, which are represented as rhombicuboctahedra. The rhombicuboctahedron is a [symmetrical] image or silhouette of the tessaract in three-dimensional space. We arrived at this relationship by means of an analogy, but it is completely correct: just as we obtained a projection of the cube onto a plane, it is also possible to represent the tessaract in three-dimensional space by means of a projection. It behaves in the same way as the silhouette of the cube in relation to the cube itself. I think that is quite easy to understand. Now I would like to tie in with the greatest image that has ever been given for this, namely Plato and Schopenhauer and the parable of the cave. Plato says: Imagine people sitting in a cave, and they are all tied up so that they cannot turn their heads and can only look at the opposite wall. Behind them are people carrying various objects past them. These people and these objects are three-dimensional. So all these [bound] people stare at the wall and see only what is cast as a shadow [of the objects] on the wall. So they would see everything in the room only as a shadow on the opposite wall as two-dimensional images. Plato says that this is how it is in the world in general. In truth, people are sitting in the cave. Now, people themselves and everything else are four-dimensional; but what people see of it are only images in three-dimensional space. This is how all the things we see present themselves. According to Plato, we are dependent on seeing not the real things, but the three-dimensional silhouettes. I only see my hand as a silhouette; in reality it is four-dimensional, and everything that people see of it is just as much an image of it as what I just showed you as an image of the Tessaract. Thus Plato was already trying to make clear that the objects we know are actually four-dimensional, and that we only see silhouettes of them in three-dimensional space. And that is not entirely arbitrary. I will give you the reasons for this in a moment. Of course, anyone can say from the outset that this is mere speculation. How can we even imagine that the things that appear on the wall have a reality? Imagine that you are sitting here in a row, and you are sitting very still. Now imagine that the things on the wall suddenly start to move. You will not be able to tell yourself that the images on the wall can move without going out of the second dimension. If something moves there, it indicates that something must have happened outside the wall, on the real object, for it to move at all. That's what you tell yourself. If you imagine that the objects in three-dimensional space can pass each other, this would not be possible with their two-dimensional silhouettes, if you think of them as substantial, that is, impenetrable. If those images, conceived substantially, wanted to move past each other, they would have to go out of the second dimension. As long as everything on the wall is at rest, I have no reason to conclude that something is happening outside the wall, outside the space of the two-dimensional silhouettes. But the moment history begins to move, I must investigate the source of the motion. And you realize that the change can only come from motion outside the wall, only from motion within a third dimension. The change has thus told us that there is a third dimension in addition to the second. What is a mere image also has a certain reality, possesses very definite properties, but differs essentially from the real object. You will not be able to deny that the mirror image is also a mere image. You see yourself in the mirror, and you are also there. If there is not a third [that is, an active being] there, then you could not actually know what you are. But the mirror image makes the same movements that the original makes; the image is dependent on the real object, the being; it itself has no ability [to move]. Thus, a distinction can be made between image and being in that only a being can bring about movement and change out of itself. I realize from the shadows on the wall that they cannot move themselves, so they cannot be beings. I have to go out of them if I want to get to the beings. Now apply this to the world in general. The world is three-dimensional. Take this three-dimensional world for itself, as it is; grasp it completely in your thoughts [for yourself], and you will find that it remains rigid. It remains three-dimensional even if you suddenly think the world frozen at a certain point in time. But there is no one and the same world in two points in time. The world is completely different at successive points in time. Imagine that these points in time cease to exist, so that what is there remains. Without time, no change would occur in the world. The world would remain three-dimensional even if it underwent no change at all. The pictures on the wall also remain two-dimensional. But change suggests a third dimension. The fact that the world is constantly changing, and that it remains three-dimensional even without change, suggests that we have to look for the change in a fourth dimension. We have to look for the reason, the cause of the change, the activity outside the third dimension, and with that you have initially uncovered the fourth of the dimensions. But with that you also have the justification for Plato's image. So we understand the whole three-dimensional world as the shadow projection of a four-dimensional world. The only question is how we have to take this fourth dimension [in reality]. You see, we have the one idea to make it clear to ourselves, of course, that it is impossible for the fourth dimension to fall [directly] into the third. That is not possible. The fourth dimension cannot fall into the third. I would like to show you now how one can, so to speak, get an idea of how to go beyond the third dimension. Imagine we have a circle – I have already tried to evoke a similar idea recently – if you imagine this circle getting bigger and bigger, then a piece of this circle becomes flatter and flatter, and because the diameter of the circle becomes very large at the end, the circle finally turns into a straight line. The line has one dimension, but the circle has two dimensions. How do you get a second dimension from a single dimension? By curving a straight line, you get a circle again. If you now imagine the surface of the circle curving into space, you first get a shell, and if you continue to do this, you get a sphere. Thus a line acquires a second dimension by curvature and a surface acquires a third dimension by curvature. If you could now curve a cube, it would have to be curved into the fourth dimension, and you would have the [spherical] tessaract. You can understand the sphere as a curved two-dimensional spatial structure. The sphere that occurs in nature is the cell, the smallest living thing. The cell is limited spherically. That is the difference between the living and the lifeless. The mineral always occurs as a crystal bounded by flat surfaces; life is bounded by spherical surfaces, built up of cells. That means that just as a crystal is built from spheres that have been straightened out, that is, from planes, so life is built from cells, that is, from spheres that have been bent together. The difference between the living and the dead lies in the way they are defined. The octahedron is defined by eight triangles. If we imagine the eight sides as spheres, we would get an eight-limbed living thing. If you curve the three-dimensional structure, the cube, again, you get a four-dimensional structure, the spherical tessaract. But if you curve the whole space, you get something that relates to three-dimensional space in the same way that a sphere relates to a plane. Just as the cube, as a three-dimensional structure, is bounded by planes, so every crystal is bounded by planes. The essence of a crystal is the assembly of [flat] boundary planes. The essence of the living is the assembly of curved surfaces, of cells. The assembly of something even higher would be a structure whose individual boundaries would be four-dimensional. A three-dimensional structure is bounded by two-dimensional structures. A four-dimensional being, that is, a living being, is bounded by three-dimensional beings, by spheres and cells. A five-dimensional being is itself bounded by four-dimensional beings, by spherical tessaracts. From this you can see that we have to ascend from three-dimensional to four-dimensional, and then to five-dimensional beings. We only have to ask ourselves: What must occur in a being that is four-dimensional?* A change must occur within the third dimension. In other words: If you hang pictures on the wall here, they are two-dimensional and generally remain static. But if you have pictures in which the second dimension moves and changes, then you must conclude that the cause of this movement can only lie outside the surface of the wall, that the third dimension of space thus indicates the change. If you find changes within the third spatial dimension itself, then you must conclude that a fourth dimension is involved, and this brings us to the beings that undergo a change within their three spatial dimensions. It is not true that we have fully recognized a plant if we have only recognized it in its three dimensions. A plant is constantly changing, and this change is an essential, a higher characteristic of it. The cube remains; it only changes its shape when you smash it. A plant changes its shape itself, that is, there is something that is the cause of this change and that lies outside the third dimension and is an expression of the fourth dimension. What is that? You see, if you have this cube and draw it, you would labor in vain if you wanted to draw it differently at different moments; it will always remain the same. If you draw the plant and compare the picture with your model after three weeks, it will have changed. So this analogy is completely accurate. Everything that lives points to something higher, where it has its true essence, and the expression of this higher is time. Time is the symptomatic expression, the appearance of liveliness [understood as the fourth dimension] in the three dimensions of physical space. In other words, all beings for whom time has an inner meaning are images of four-dimensional beings. This cube is still the same after three or six years. The lily bud changes. Because for it, time has a real meaning. Therefore, what we see in the lily is only the three-dimensional image of the four-dimensional lily being. So time is an image, a projection of the fourth dimension, the organic liveliness, into the three spatial dimensions of the physical world. To understand how a following dimension relates to the preceding one, please imagine the following: a cube has three dimensions; when you visualize the third, you have to remember that it is perpendicular to the second, and the second is perpendicular to the first. The three dimensions are characterized by the fact that they are perpendicular to one another. But we can also imagine how the third dimension arises from the following [fourth dimension]. Imagine that you would change the cube by coloring the boundary surfaces and then changing these colors [in a certain way, as in Hinton's example]. Such a change can indeed be made, and it corresponds exactly to the change that a three-dimensional being undergoes when it passes into the fourth dimension, when it develops through time. If you cut a four-dimensional being at any point, you take away the fourth dimension, you destroy it. If you do that to a plant, you do exactly the same thing as if you were to make a cast of the plant, a plaster cast. You have captured that by destroying the fourth dimension, time. Then you get a three-dimensional object. If for any three-dimensional being the fourth dimension, time, has an essential significance, then it is a living being. Now we enter the fifth dimension. You can say to yourself that you must again have a boundary that is perpendicular to the fourth dimension. We have seen that the fourth dimension is related to the third dimension in a similar way to the third dimension being related to the second. It is not immediately possible to visualize the fifth dimension in this way. But you can again create a rough idea by using an analogy. How does a dimension come into being in the first place? If you simply draw a line, you will never create another dimension by simply pushing the line in one direction. Only by imagining that you have two opposing directions of force, which then accumulate at a point, only by expressing the accumulation, do you have a new dimension. We must therefore be able to grasp the new dimension as a new line of accumulation [of two currents of force], and imagine the one dimension coming from the right one time and from the left the next, as positive and negative. So I understand a dimension [as a polar [stream of forces] within itself], so that it has a positive and a negative dimension [component], and the neutralization [of these polar force components] is the new dimension. From there, we want to create an idea of the fifth dimension. We will have to imagine that the fourth dimension, which we have found expressed as time, behaves in a positive and negative way. Now take two beings for whom time has a meaning, and imagine two such beings colliding with each other. Then something must appear as a result, similar to what we have previously called an accumulation of [opposing] forces; and what arises as a result when two four-dimensional beings come into relation with each other is their fifth dimension. This fifth dimension arises as a result, as a consequence of an exchange [a neutralization of polar force effects], in that two living beings, through their mutual interaction, produce something that they do not have outside [in the three ordinary spatial dimensions together], nor do they have in [the fourth dimension,] time, but have completely outside these [previously discussed dimensions or] boundaries. This is what we call compassion [or feeling], by which one being knows another, thus the realization of the [spiritual and mental] inner being of another being. A being could never know anything about another being outside of time [and space] if you did not add a higher, fifth dimension, [i.e. enter the world of] sensation. Of course, here the sensation is only to be understood as a projection, as an expression [of the fifth dimension] in the physical world. Developing the sixth dimension in the same way would be too difficult, so I will only indicate it. [If we tried to progress in this way, something could be developed as an expression of the sixth dimension that,] when placed in the three-dimensional physical world, is self-conscious. Man, as a three-dimensional being, is one who shares his imagery with other three-dimensional beings. The plant, in addition, has the fourth dimension. For this reason, you will never find the ultimate essence of the plant within the three dimensions of space, but you would have to ascend from the plant to a fourth spatial dimension [to the astral sphere]. But if you wanted to grasp a being that has feeling, you would have to ascend to the fifth dimension [to the lower Devachan, to the Rupa sphere]; and if you wanted to grasp a being that has self-awareness, a human being, you would have to ascend to the sixth dimension [to the upper Devachan, to the Arupa sphere]. Thus, the human being as he stands before us in the present is indeed a six-dimensional being. That which is called feeling or compassion, or self-awareness, is a projection of the fifth or sixth dimension into ordinary three-dimensional space. Man extends into these spiritual spheres, albeit unconsciously for the most part; only there can he actually be experienced in the sense indicated last. This six-dimensional being can only come to an idea of even the higher worlds if it tries to get rid of the actual characteristics of the lower dimensions. I can only hint at the reason why man considers the world to be only three-dimensional, namely because he is conditioned in his perception to see only a reflection of something higher in the world. When you look in a mirror, you also see only a reflection of yourself. Thus, the three dimensions of our physical space are indeed reflections, material copies of three higher, causally creative dimensions. Our material world therefore has its polar [spiritual] counter-image in the group of the three next higher dimensions, that is, in those of the fourth, fifth and sixth dimensions. And in a similar sense, the spiritual worlds that lie beyond this group of dimensions, which can only be sensed, are also polar to those of the fourth to sixth dimensions. If you have water and you let the water freeze, the same substance is present in both cases; but in form they differ quite substantially. You can imagine a similar process for the three higher dimensions of man. If you think of man as a purely spiritual being, then you have to think of him as having only the three higher dimensions – self-awareness, feeling and time – and these three dimensions are reflected in the physical world in its three ordinary dimensions. The yogi [secret student], if he wants to advance to a knowledge of the higher worlds, must gradually replace the mirror images with reality. For example, when he looks at a plant, he must get used to gradually substituting the higher dimensions for the lower ones. If he looks at a plant and is able to abstract from one spatial dimension in the case of a plant, to abstract from one spatial dimension and instead to imagine a corresponding one of the higher dimensions, in this case time, then he actually gets an idea of what a two-dimensional, moving being is. To make this being more than just an image, to make it correspond to reality, the yogi must do the following. If he disregards the third dimension and adds the fourth, he would only get something imaginary. However, the following mental image can help: when we make a cinematographic representation of a living being, we remove the third dimension from the original three-dimensional processes, but add the [dimension of] time through the sequence of images. If we then add sensation to this [moving] perception, we perform a procedure similar to what I described earlier as the bending of a three-dimensional structure into the fourth dimension. Through this process you then get a four-dimensional entity, but now one that has two of our spatial dimensions, but also two higher ones, namely time and sensation. Such beings do indeed exist, and these beings - and this brings me to a real conclusion to the whole consideration - I would like to tell you about. Imagine two spatial dimensions, that is, a surface, and this surface endowed with motion. Now imagine a bent as a sensation, a sentient being that then pushes a two-dimensional surface in front of it. Such a being must act differently and be very different from a three-dimensional being in our space. This flat creature that we have constructed in this way is incomplete in one direction, completely open, and offers you a two-dimensional view; you cannot go around it, it comes towards you. This is a luminous creature, and the luminous creature is nothing other than the incompleteness in one direction. Through such a being, the initiates then get to know other beings, which they describe as divine messengers approaching them in flames of fire. The description of Mount Sinai, where Moses received the Ten Commandments,® means nothing other than that a being could indeed approach him that, to his perception, had these dimensions. It appeared to him like a human being from whom the third spatial dimension had been removed; it appeared in sensation and in time. These abstract images in the religious documents are not just external symbols, but powerful realities that man can get to know if he is able to appropriate what we have tried to make clear through analogies. The more you devote yourself diligently and energetically to such considerations of analogies, the more you really work on your mind, and the more these [considerations] work in us and trigger higher abilities. [This is roughly the case when dealing with] the analogy of the relationship of the cube to the hexagon and the tessaract to the rhombic dodecahedron. The latter represents a projection of the tessaract into the three-dimensional physical world. If you visualize these figures as living entities, if you allow the cube to grow out of the projection of the die – the hexagon – and likewise allow the tessaract itself to arise from the projection of the tessaract [the rhombic dodecahedron], then you create the possibility and the ability in your lower mental body to grasp what I have just described to you as a structure. And if, in other words, you have not only followed me but have gone through this procedure vividly, as the yogi does in an awakened state of consciousness, then you will notice that something will occur to you in your dreams that in reality is a four-dimensional entity, and then it is not much further to bring it over into the waking consciousness, and you can then see the fourth dimension in every four-dimensional being. The astral sphere is the fourth dimension. Devachan to rupa is the fifth dimension. Devachan to arupa is the sixth dimension. These three worlds, the physical, astral and celestial [devachan], comprise six dimensions. The even higher worlds are completely polar to these. Mineral Plant Animal Human Arupa Self-consciousness Rupa Sensation Self-consciousness Astral plane Life Sensation Self-consciousness Physical form Life Sensation Self-plan consciousness Form Life Sensation Form Life Form |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): Four-Dimensional Space

07 Nov 1905, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| I pin the paper tape together tightly with pins and cut it in half. Now one tape is firmly stuck inside the other. Before that, it was just one tape. So here, by merely intertwining the tapes within the three dimensions, I have created the same thing that I would otherwise have to reach out into the [fourth] dimension to achieve." |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): Four-Dimensional Space

07 Nov 1905, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

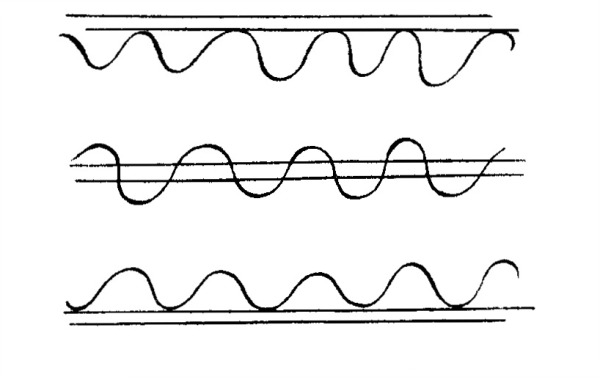

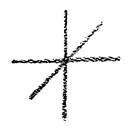

Our ordinary space has three dimensions: length, width and height. A line extends in one dimension, it has only length. A table is a surface, so it has two dimensions: length and width. A body extends in three dimensions. How does a body of three dimensions come about? Imagine a shape that has no dimensionality at all: that is the point. It has zero dimensions. When a point moves in one direction, a straight line is created, a one-dimensional shape. If you imagine the line continuing, a surface with length and width is created. Finally, if you imagine the surface moving, it describes a three-dimensional shape. But we cannot use the same method to create a fourth dimension from a three-dimensional object [through movement]. We must try to visualize how we can arrive at the concept of a fourth dimension. [Certain] mathematicians [and natural scientists] have felt compelled to harmonize the spiritual world with our sensual world [by placing the spiritual world in a four-dimensional space], for example, Zöllner.  Imagine a circle. It is closed on all sides in the plane. If someone demands that a coin should come into the circle from outside, we have to cross the circle line (Figure 46). But if you do not want to touch the circle line, you have to lift the coin [into the space] and then put it in. You must necessarily go from the second to the third dimension. If we wanted to conjure a coin into a cube [or into a sphere], we would have to go [out of the third dimension and] through the fourth dimension.' In this life, the first time I began to grasp what space actually is was when I started to study recent [synthetic projective] geometry. Then I realized what it means to go from a circle to a line (Figure 47). In the most intimate thinking of the soul, the world opens up.  Now let us imagine a circle. If we follow the circle line, we can walk around it and return to the original point. Now let us imagine the circle getting bigger and bigger [holding a tangent line]. In the end, it must merge into a straight line because it flattens out more and more. [When I go through the enlarging circles, I always go down on one side and then come up on the other side and back to the starting point. If I finally move on the straight line, for example to the right into infinity, I have to return from the other side of infinity, since the straight line behaves like a circle in terms of the arrangement of its points. From this we see that space has no end [in the same sense that the straight line has no end, that is, the arrangement of its points is the same as in a closed circle. Accordingly, we must think of infinitely extended space as closed in itself, just as the surface of a sphere is closed in itself]. Thus you have represented infinite space [in the sense of] a circle [or] a sphere. This concept leads us to imagine space in its reality. If I now imagine that I do not simply disappear [into infinity] and then return [unchanged from the other side], but think to myself that I have a radiating light, this will become weaker and weaker as I move away (seen from a stationary point on the line) and stronger and stronger when I return (with the light from infinity). And if we consider that this light not only has a positive effect, but, as it approaches from the other side here, shines all the more strongly, then you have [here the qualities] positive and negative. In all natural effects, you will find these two poles, which represent nothing other than the opposite effects of space. From this you get the idea that space is something powerful, and that the forces that work in it are nothing other than the outflow of the power itself. Then we will have no doubt that within our three-dimensional space there could be a force that works from within. You will realize that everything that occurs in space is based on real relationships in space. If we were to intertwine two dimensions, we would have brought these two into relation. If you want to entwine two [closed] rings, you have to unravel one of them to get the other inside. But now I will demonstrate the inner diversity of space by entwining this structure [a rectangular paper band] twice around itself [that is, holding one end and twisting the other end 360° and then holding the two ends together]. I pin the paper tape together tightly with pins and cut it in half. Now one tape is firmly stuck inside the other. Before that, it was just one tape. So here, by merely intertwining the tapes within the three dimensions, I have created the same thing that I would otherwise have to reach out into the [fourth] dimension to achieve." This is not a gimmick, but reality. If we have the sun here, and the earth's orbit around the sun here, and the moon's orbit around the earth here (Figure 48), we have to imagine that the earth moves around the sun and therefore the moon's orbit and the earth's orbit are intertwined exactly [like our two paper ribbons]. Now the moon has branched off from the earth [in the course of the earth's development]. This is an internal bifurcation that has occurred in the same way [as the intertwining of our two paper ribbons]. [Through such a way of looking at it] space comes alive in itself.  Now consider a square. Imagine it moving through space in such a way that it forms a cube. Then it must progress within itself. A cube is composed of six squares, which together form the surface of the cube. To put the cube together [in a clear way], I first place the six squares next to each other [in a plane] (Figure 49). I get the cube again when I put these squares on top of each other. I then have to place the sixth on top by going through the third dimension. Thus I have now laid the cube out in two dimensions. I have transformed a three-dimensional structure by laying it out in two dimensions.  Now imagine that the boundaries of a cube are squares. If I have a three-dimensional cube here, it is bounded by two-dimensional squares. Let's just take a single square. It is two-dimensional and is bounded by four one-dimensional lines. I can expand the four lines into a single dimension (Figure 50). What appears in the one dimension, I will now paint in red [solid line] and the other dimension in blue [dotted line]. Now, instead of saying length and width, I can speak of the red and blue dimensions.  I can reassemble the cube from six squares. So now I go from the number four [the number of side lines of the square] to the number six [the number of the side surfaces of the cube]. If I go one step further, I get from the number six [the number of the side surfaces of the cube] to the number eight [the number of “side cubes” of a four-dimensional structure]. I now arrange the eight cubes in such a way that the corresponding structure is created in three-dimensional space to that which was previously constructed in two-dimensional space (Figure 51) from six squares.  Imagine that I could turn this structure inside out so that I could turn it right way up and put it together in such a way that I could cover the whole structure with the eighth cube. Then I would get a four-dimensional structure in a four-dimensional space from the eight cubes. This figure is called [by Hinton] the tessaract. Its limiting figure is eight cubes, just as the ordinary cube has six squares as its limiting figure. The [four-dimensional] tessaract is therefore bounded by [eight] three-dimensional cubes. Imagine a creature that can only see in two dimensions, and this creature would now look at the squares laid out separately, it would only see the squares 1, 2, 3, 4 and 6, but never the hatched square 5 in the middle (Figure 52). It is quite the same for you with the four-dimensional structure. [Since you can only see three-dimensional objects, you] cannot see the hidden cube in the middle.  Now imagine the cube drawn on the board like this [so that the outline forms a regular hexagon]. The other side is hidden behind it. This is a kind of silhouette, a projection of the cube into two-dimensional space (Figure 53). This two-dimensional silhouette of a three-dimensional cube consists of rhombi, oblique rectangles [parallelograms]. If you imagine the cube made of wire, you would also be able to see the rhomboid squares at the back. So here you have six interlocking rhomboid squares in the projection. In this way you can project the whole cube into two-dimensional space.  Now imagine our tetrahedron formed in four-dimensional space. If you project this figure into three-dimensional space, you should get four non-intersecting rhombic parallelpipeds. One of these rhombic parallelpipeds should be drawn as follows (Figure 54).  Eight such shifted rhombic cubes would have to be inserted into each other in order to obtain a three-dimensional image of the four-dimensional tessaract in three-dimensional space. Thus, we can represent the three-dimensional shadow image of such a tessaract with the help of eight rhombic cubes that are suitably inserted into each other. The spatial structure that results is a rhombic dodecahedron with four spatial diagonals (Figure 55). Just as in the rhombus representation of the cube, three directly neighboring rhombuses are shifted into each other, so that only three of the six cube surfaces are seen in the projection, only four non-intersecting rhombic cubes appear in the rhombic dodecahedron only four non-intersecting rhombic cubes appear as projections of the eight boundary cubes, since four of the directly neighboring rhombic cubes completely cover the remaining four.'>  We can construct the three-dimensional shadow of a four-dimensional body, but not the tessaract itself. In the same sense, we are the shadows of four-dimensional beings. Thus, as man rises from the physical to the astral, he must develop his powers of visualization. Let us imagine a two-dimensional being who makes an [intense and repeated] effort to vividly imagine such a [three-dimensional] shadow image. When it then surrenders to the dream, then (...). When you mentally build up the relationship between the third and fourth dimensions, the forces at work within you allow you to see into [real, not mathematical] four-dimensional space. We will always be powerless in the higher world if we do not acquire the abilities [to see in the higher world] here [in the world of ordinary consciousness]. Just as a person in the womb develops eyes to see in the physical-sensual world, so must a person in the womb of the earth develop [supernatural] organs, then he will be born in the higher world [as a seer]. The development of the eyes in the womb is an [illuminating] example [of this process]. The cube would have to be constructed from the dimensions of length, width and height. The tessaract would have to be constructed from the dimensions of length, width, height and a fourth dimension. As the plant grows, it breaks through three-dimensional space. Every being that lives in time breaks through the three [ordinary] dimensions. Time is the fourth dimension. It is invisibly contained in the three dimensions of ordinary space. However, you can only perceive it through clairvoyant power. A moving point creates a line; when a line moves, a surface is created; and when a surface moves, a three-dimensional body is created. If we now let the three-dimensional space move, we have growth [and development]. This gives you four-dimensional space, time [projected into three-dimensional space as movement, growth, development]. [The geometric consideration of the structure of the three ordinary dimensions] can be found in real life. Time is perpendicular to the three dimensions, it is the fourth, and it grows. When you bring time to life within you, sensation arises. If you increase the time within you, move it within yourself, you have the sentient animal being, which in truth has five dimensions. The human being actually has six dimensions. We have four dimensions in the etheric realm [astral plane], five dimensions in the astral realm [lower devachan] and six dimensions in the [upper] devachan. Thus the [spiritual] manifoldness swells up to you. The devachan, as a shadow cast into the astral realm, gives us the astral body; the astral realm, as a shadow cast into the etheric realm, gives us the etheric body, and so on. Time flows in one direction, which is the withering away of nature, and in the other direction it is the revival. The two points where they merge are birth and death. The future is constantly coming towards us. If life only went in one direction, nothing new would ever come into being. Man also has genius – that is his future, his intuitions, which flow towards him. The processed past is [the stream coming from the other side; it determines] the essence [of how it has become so far]. |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): On Higher-Dimensional Space

22 Oct 1908, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Those who are not capable of very sharp abstractions will already falter here. For example, you cannot cut the boundaries of a wax cube as a fine layer of wax. You would still get a layer of a certain thickness, so you would get a body. |

| 324a. The Fourth Dimension (2024): On Higher-Dimensional Space

22 Oct 1908, Berlin Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

The subject we are to discuss today will present us with a number of difficulties. Consider the lecture as an episode; it is being held at your request. If you only want to grasp the subject formally in its depth, some mathematical knowledge is necessary. But if you want to grasp it in its reality, you have to penetrate very deeply into occultism. So today we can only talk about it very superficially, only give a suggestion for this or that. It is very difficult to talk about multidimensionality at all, because if you want to get an idea of what more than three dimensions are, you have to delve into abstract areas, and there the concepts must be very precisely and strictly defined, otherwise you end up in a bottomless pit. And that's where many friends and enemies have ended up. The concept of multidimensional space is not as foreign to the world of mathematicians as one might think.® In mathematical circles, there is already a way of calculating with a multidimensional type of calculation. Of course, the mathematician can only speak of this space in a very limited sense; he can only discuss the possibility. Whether it really is can only be determined by someone who can see into a multidimensional space. Here we are already dealing with a lot of concepts that, if we grasp them precisely, really provide us with clarity about the concept of space. What is space? We usually say: there is space around me, I walk around in space — and so on. If you want a clearer idea, you have to go into some abstractions. We call the space in which we move three-dimensional. It has an extension in height and depth, to the right and left, to the front and back, it has length, width and height. When we look at bodies, these bodies are extended for us in this three-dimensional space; they have a certain length, a certain width and height for us. However, we have to deal with the details of the concept of space if we want to arrive at a more precise concept. Let us look at the simplest body, the cube. It shows us most clearly what length, width and height are. We find a base of the cube that is the same in length and width. If we move the base up, just as far as the base is wide and long, we get the cube, which is therefore a three-dimensional object. The cube is the clearest way for us to learn about the details of a three-dimensional object. We examine the boundaries of the cube. These are formed everywhere by surfaces bounded by sides of equal length. There are six such surfaces. What is a surface? Those who are not capable of very sharp abstractions will already falter here. For example, you cannot cut the boundaries of a wax cube as a fine layer of wax. You would still get a layer of a certain thickness, so you would get a body. We will never get to the boundary of the cube this way. The real boundary has only length and width, no height. Thickness is eliminated. We thus arrive at the formulaic sentence: The area is the boundary [of a three-dimensional object] in which one dimension is eliminated. What then is the boundary of a surface, for example of a square? Here we must again take the most extreme abstraction. [The boundary of a surface] is a line that has only one dimension, length. The width is canceled. What is the boundary of a line? It is the point, which has no dimension at all. So you always get the boundary of a thing by leaving out a dimension. So you could say to yourself, and this is also the line of thought that many mathematicians have followed, especially Riemann,* who has achieved the most solid work here: We take the point, which has none, the line, which has one, the plane, which has two, the solid, which has three dimensions. Now mathematicians asked themselves: Could it not be that formally one could say that one could add a fourth dimension? Then the [three-dimensional] body would have to be the boundary of the four-dimensional object, just as the surface is the boundary of the body, the line is the boundary of the surface, and the point is the boundary of the line. Of course, the mathematician then goes even further to five-, six- and seven-dimensional objects and so on. We have [even arbitrary] “-dimensional objects [where ” is a positive integer]. Now, there is already some ambiguity in the matter when we say: the point has none, the line has one, the plane two, the solid three dimensions. We can now make such a solid, for example a cube, out of wax, silver, gold and so on. They are different in terms of matter. We make them the same size, then they all occupy the same space. If we now eliminate all material, only a certain part of space remains, which is the spatial image of the body. These parts of space are the same [among themselves], regardless of what material the cube was made of. These parts of space also have length, width and height. We can now imagine these cubes as infinitely extended and thus arrive at an infinitely extended three-dimensional space. The (material) body is, after all, only a part of it. The question now is whether we can simply extend such conceptual considerations, which we make starting from space, to higher realities. In these considerations, the mathematician actually only calculates, and does so with numbers. Now the question is whether one can do that at all. I will show you how much confusion can arise when calculating with spatial quantities. Why? I only need to tell you one thing: Imagine you have a square figure here. I can make this figure, this area, wider and wider on both sides and thus arrive at an area that extends indefinitely between two lines (Figure 56).  This area is infinitely large, so it is >. Now imagine someone who hears that the area between these two lines is infinite. Of course, he thinks of infinity. If you now talk to him about infinity, he may have very wrong ideas about it. Imagine that I now add below [each square one more, so another row of] an infinite number of squares, and I get a [different] infinity that is exactly twice as large as the first (Figure 57). So we have > = 2 + 0, In the same way I could get: “ = 3 +, In calculating with numbers, you can just as well use infinity as finiteness. Just as it is true that space was already infinite in the first case, it is just as true that it is 2 + c, 3 - c, and so on. So we are calculating numerically here.  We see that the concept of the infinity of space [which follows from the numerical representation] does not give us any possibility of penetrating deeper [into the higher realities]. Numbers actually have no relation to space at all, they relate to it quite neutrally, like peas or any other objects. You now know that nothing changes in reality as a result of calculation. If someone has three peas, multiplication does not change that, even if the calculation is done correctly. The calculation 3 + 3 = 9 does not give nine peas. A mere consideration does not change anything here, and calculation is a mere consideration. Just as three peas are left behind, [you do not actually create nine peas,] even if you multiply correctly, three-dimensional space must also be left behind if the mathematician also calculates: two-, three-, four-, five-dimensional space. You will feel that there is something very convincing about such a mathematical consideration. But this consideration only proves that the mathematician could indeed calculate with such a multidimensional space; [but whether a multidimensional space actually exists, that is,] he cannot determine anything about the validity of such a concept [for reality]. Let us be clear about that here in all strictness. Now we want to consider some other considerations that have been made very astutely by mathematicians, one might say. We humans think, hear, feel and so on in three-dimensional space. Let us imagine that there are beings that could only perceive in two-dimensional space, that would be organized so that they always have to remain in the plane, that they could not get out of the second dimension. Such beings are quite conceivable: they can only move [and perceive] to the right and left [and backwards and forwards] and have no idea of what is above and below. Now it could be the same for man in his three-dimensional space. He could only be organized for the three dimensions, so that he could not perceive the fourth dimension, but for him it arises just as the third arises for the others. Now mathematicians say that it is quite possible to think of man as such a being. But now one could say that this is also only one interpretation. One could certainly say that. But here one must again proceed somewhat more precisely. The matter is not as simple as in the first case [with the numerical determination of the infinity of space]. I am intentionally only giving very simple discussions today. This conclusion is not the same as the first purely formal [calculative] consideration. Here we come to a point where we can take hold. It is true that there can be a being that can only perceive what moves in the plane, that has no idea that there is anything above or below. Now imagine the following: Imagine that a point becomes visible to the being within the surface, which is of course perceptible because it is located in the surface. If the point only moves within the surface, it remains visible; but if it moves out of the surface, it becomes invisible. It would have disappeared for the surface being. Now let us assume that the point reappears, thus becoming visible again, only to disappear again, and so on. The being cannot follow the point [as it moves out of the surface], but the being can say to itself: the point has now gone somewhere I cannot see. The being with the surface vision could now do one of two things. Let us put ourselves in the place of the soul of this flat creature. It could say: There is a third dimension into which the object has disappeared, and then it has reappeared afterwards. Or it could also say: These are very foolish creatures who speak of a third dimension; the object has always disappeared, perished and been reborn [in every case]. One would have to say: the being sins against reason. If it does not want to assume a continuous disappearance and re-emergence, the being must say to itself: the object has submerged somewhere, disappeared, where I cannot see. A comet, when it disappears, passes through four-dimensional space. We see here what we have to add to the mathematical consideration. There should be something in the field of our observations that always emerges and disappears again. You don't need to be clairvoyant for that. If the surface being were clairvoyant, it wouldn't need to conclude, because it would know from experience that there is a third dimension. It is the same for humans. Unless they are clairvoyant, they would have to say: I remain in the three dimensions; but as soon as I observe something that disappears from time to time and reappears, I am justified in saying: there is a fourth dimension here.Everything that has been said so far is as unassailable as it can possibly be. And the confirmation is so simple that it will not even occur to man in his present deluded state to admit it. The answer to the question: Is there something that always disappears and reappears? — is so easy. Just imagine, a feeling of joy arises in you and then it disappears again. It is impossible that anyone who is not clairvoyant will perceive it. Now the same sensation reappears through some event. Now you, just like the surface creature, could behave in different ways. Either you say to yourself that the sensation has disappeared somewhere where I cannot follow it, or you take the view that the sensation passes away and arises again and again. But it is true: every thought that has vanished into the unconscious is proof that something disappears and then reappears. At most, the following can be objected to: if you endeavor to object to such a thought, which is already plausible to you, with everything that could be objected to from a materialistic point of view, you are quite right. I will make the most subtle objection here, all the others are very easy to refute. For example, one says to oneself: everything is explained in a purely materialistic way. Now I will show you that something can quite well disappear within material processes, only to reappear later. Imagine that some kind of vapor piston is always acting in the same direction. It can be perceived as a progressive piston as long as the force is acting. Now suppose I set a piston that is exactly the same but acting in the opposite direction. Then the movement is canceled out and a state of rest sets in. So here the movement actually disappears. In the same way, one could say here: For me, the sensation of joy is nothing more than molecules moving in the brain. As long as this movement takes place, I feel this joy. Now, let us assume that something else causes an opposite movement of the molecules in the brain, and the joy disappears. Wouldn't someone who doesn't go very far with their considerations find a very meaningful objection here? But let's take a look at what this objection is actually about. Just as one [piston] movement disappears when the opposite [piston movement] occurs, so the [molecular movement underlying the sensation] is extinguished by the opposite [molecular movement]. What happens when one piston movement extinguishes the other? Then both movements disappear. The second movement also disappears immediately. The second movement cannot extinguish the first without itself being extinguished. [A total standstill results, no movement whatsoever remains.] Yes, but then a [new] sensation can never extinguish the [already existing] sensation [without perishing itself]. So no sensation that is in my consciousness could ever extinguish another [without extinguishing itself in the process]. It is therefore a completely false assumption that one sensation could extinguish another [at all]. [If that were the case, no sensation would remain, and a totally sensationless state would arise.] Now, at most, it could be said that the first sensation is pushed into the subconscious by the second. But then one admits that something exists that eludes our [immediate] observation. We have not considered any clairvoyant observations today, but have only spoken of purely mathematical ideas. Now that we have admitted the possibility of such a four-dimensional world, we ask ourselves: Is there a way to observe something [four-dimensional] without being clairvoyant? — Yes, but we have to use a kind of projection to help us. If you have a piece of a surface, you can rotate it so that the shadow becomes a line. Similarly, you can get a point from a line as a shadow. For a [three-dimensional] body, the silhouette is a [two-dimensional] surface. Likewise, one can say: So it is quite natural, if we are aware that there is a fourth dimension, that we say: [Three-dimensional] bodies are silhouettes of four-dimensional entities.  Here we have arrived at the idea of [four-dimensional space] in a purely geometrical way. But [with the help of geometry] this is also possible in another way. Imagine a square, which has two dimensions. If you imagine the four [bounding] lines laid down next to each other [i.e., developed], you have laid out the [boundary figures] of a two-dimensional figure in one dimension (Figure 58). Let's move on. Imagine we have a line. If we proceed in the same way as with the square, we can also decompose it into two points [and thus decompose the boundaries of a one-dimensional structure into zero dimensions]. You can also decompose a cube into six squares (Figure 59). So there we have the cube in terms of its boundaries decomposed into surfaces, so that we can say: a line is decomposed into two points, a surface into four lines, a cube into six surfaces. We have the numerical sequence two, four, six here.  Now we take eight cubes. Just as [the above developments each consist of] unfolded boundaries, here the eight cubes form the boundary of the four-dimensional body (Figure 60). The [development of these] boundaries forms a double cross, which, we can say, indicates the boundaries of the regular [four-dimensional] body. [This body, a four-dimensional cube, is named the Hinton Tessaract after Hinton.]  We can therefore form an idea of the boundaries of this body, the tessaract. We have here the same idea of the four-dimensional body as a two-dimensional being could have of a cube, for example by unfolding the boundaries. |

| 326. The Origins of Natural Science: Lecture III

26 Dec 1922, Dornach Tr. Maria St. Goar, Norman MacBeth Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Hence they felt that if they could express the world in thoughts arranged in the same clear-cut architectural order as in a mathematical or geometrical system, they would thereby achieve something that would have to correspond to reality. |

| 326. The Origins of Natural Science: Lecture III

26 Dec 1922, Dornach Tr. Maria St. Goar, Norman MacBeth Rudolf Steiner |

|---|