| 294. Practical Course for Teachers: On Drawing up the Time-table

04 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In this all long vowels were pronounced short and all short vowels long, and whereas the dialect quite correctly talked of “Die Sonne” (the sun), the Austrian school language did not say “Die Sonne” but “Die Sohne,” and this habit of talking becomes involuntary; one is constantly relapsing into it, as a cat lands on his paws. But it is very unsettling for the teacher too. The further one travels from north to south the more does one sink in the slough of this evil. |

| 294. Practical Course for Teachers: On Drawing up the Time-table

04 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

You will have seen from these lectures, which lay down methods of teaching, that we are gradually nearing the mental insight from which should spring the actual timetable. Now I have told you on different occasions already that we must agree, with regard to what we accept in our school and how we accept it, to compromise with conditions already existing. For we cannot, for the time being, create for the Waldorf School the entire social world to which it really belongs. Consequently, from this surrounding social world there will radiate influences which will continually frustrate the ultimate ideal time-table of the Waldorf School. But we shall only be good teachers of the Waldorf School if we know in what relation the ideal time-table stands to the time-table which we will have to use at first because of the ascendancy of the social world outside. This will result for us in the most vital difficulties which we must therefore mention before going on, and these will arise in connection with the pupils, with the children, immediately at the beginning of the elementary school period and then again at the end. At the very beginning of the elementary school course there will, of course, be difficulties, because there exist the time-tables of the outside world. In these time-tables all kinds of educational aim are required, and we cannot risk letting our children, after the first or second year at school, fall short of the learning shown by the children educated and taught outside our school. After nine years of age, of course, by our methods our children should have far surpassed them, but in the intermediate stage it might happen that our children were required to show in some way, let us say, at the end of the first year in school, before a board of external commissioners, what they can do. Now it is not a good thing for the children that they should be able to do just what is demanded to-day by an external commission. And our ideal time-table would really have to have other aims than those set by a commission of this kind. In this way the dictates of the outside world partially frustrate the ideal time-table. This is the case with the beginning of our course in the Waldorf School. In the upper classes1 of the Waldorf School, of course, we are concerned with children, with pupils who have come in from other educational institutions, and who have not been taught on the methods on which they should have been taught. The chief mistake attendant to-day on the teaching of children between seven and twelve is, of course, the fact that they are taught far too intellectually. However much people may hold forth against intellectualism, the intellect is considered far too much. We shall consequently get children coming in with already far more pronounced characteristics of old age—even senility—than children between twelve and fourteen should show. That is why when, in these days, our youth itself appears in a reforming capacity, as with the Scouts (Pfadfinder) and similar movements, where it makes its own demands as to how it is to be educated and taught, it reveals the most appalling abstractness, that is, senility. And particularly when youth desires, as do the “Wandervögel,” to be taught really youthfully, it craves to be taught on senile principles. That is an actual fact to-day. We came up against it very sharply ourselves in a commission on culture, where a young Wandervögel, or member of some youth movement, got up to speak. He began to read off his very tedious abstract statements of how modern youth desires to be taught and educated. They were too boring for some people because they were nothing but platitudes; moreover, they were platitudes afflicted with senile decay. The audience grew restless, and the young orator hurled into its midst: “I declare that the old folks to-day do not understand youth.” The only fact in evidence, however, was that this half-child was too much of an old man because of a thwarted education and perverted teaching. Now this will have to be taken most seriously into account with the children who come into the school at twelve to fourteen, and to whom, for the time being, we are to give, as it were, the finishing touch. The great problems for us arise at the beginning and end of the school years. We must do our utmost to do justice to our ideal time-table, and we must do our utmost not to estrange children too greatly from modern life. But above all we must seek to include in the first school year a great deal of simple talking with the children. We read to them as little as possible, but prepare our lessons so well that we can tell them everything that we want to teach them. We aim at getting the children to tell again what they have heard us tell them. But we do not adapt reading-passages which do not fire the fantasy; we use, wherever possible, reading-passages which excite the imagination profoundly; that is, fairy tales. As many fairy tales as possible. And after practising for some time with the child this telling of stories and retelling of them, we encourage him a little to tell very shortly his own experiences. We let him tell us, for instance, about something which he himself likes to tell about. In all this telling of stories, and telling them over, and telling about personal experiences, we guide, quite un-pedantically, the dialect into the way of educated speech, by simply correcting the mistakes which the child makes—at first he will do nothing but make mistakes, of course; later on, fewer and fewer. We show him, by telling stories and having them retold, the way from dialect to educated conversation. We can do all this, and in spite of it the child will have reached the standard demanded of him at the end of the first school year. Then, indeed, we must make room for something which would be best absent from the very first year of school and which is only a burden on the child's soul: we shall have to teach him what a vowel is, and what a consonant is. If we could follow the ideal time-table we would not do this in the first school year. But then some inspector might turn up at the end of the first year and ask the child what “i” is, what “l” is, and the child would not know that one is a vowel and the other a consonant. And we should be told: “Well, you see, this ignorance comes of Anthroposophy.” For this reason we must take care that the child can distinguish vowels from consonants. We must also teach him what a noun is, what an article is. And here we find ourselves in a real dilemma. For according to the prevailing time-table we ought to use German terms and not say “artikel.” We have to talk to the child, according to current regulations, of “Geschlechtswort” (gender-words) instead of “artikel,” and here, of course, we find ourselves in the dilemma. It would be better at this point not to be pedantic and to retain the word “artikel.” Now I have already indicated how a noun should be distinguished from an adjective by showing the child that a noun refers to objects in space around him, to self-contained objects. You must try here to say to him: “Now take a tree: a tree is a thing which goes on standing in space. But look at a tree in winter, look at a tree in spring, and look at a tree in summer. The tree is always there, but it looks different in winter, in summer, in spring. In winter we say: ‘It is brown.’ In spring we say: ‘It is green.’ In summer we say: ‘It is leafy.’ These are its attributes.” In this way we first show the child the difference between something which endures and its attributes, and say: “When we use a word for what persists, it is a noun; when we use a word for the changing quality of something that endures it is an adjective.” Then we give the child an idea of activity: “Just sit down on your chair. You are a good child. Good is an adjective. But now stand up and run. You are doing something. That is an action.” We describe this action by a verb. That is, we try to draw the child up to the thing, and then we go from the thing over to the words. In this way, without doing the child too much harm, we shall be able to teach him what a noun is, an article, an adjective, a verb. The hardest of all, of course, is to understand what an article is, because the child cannot yet properly understand the connection of the article with the noun. We shall flounder fairly badly in an abstraction when we try to teach him what an article is. But he has to learn it. And it is far better to flounder in abstractions over it because it is unnatural in any case, than to contrive all kinds of artificial devices for making clear to the child the significance and the nature of the article, which is, of course, impossible. In short, it will be a good thing for us to teach with complete awareness that we are introducing something new into teaching. The first school year will afford us plenty of opportunity for this. Even in the second year a good deal of this awareness will invade our teaching. But the first year will include much that is of great benefit to the growing child. The first school year will include not only writing, but an elementary, primitive kind of painting-drawing, for this is, of course, our point of departure for teaching writing. The first school year will include not only singing, but also an elementary training in the playing of a musical instrument. From the first we shall not only let the child sing, but we shall take him to the instrument. This, again, will prove a great boon to the child. We teach him the elements of listening by means of sound-combinations. And we try to preserve the balance between the production of music from within by song, and the hearing of sounds from outside, or by making them on the instrument. These elements, painting-drawing, drawing with colours, finding the way into music, will provide for us, particularly in the first school year, a wonderful element of that will-formation which is almost quite foreign to the school of to-day. And if we further transform the little mite's physical training into Eurhythmy we shall contribute in a quite exceptional degree to the formation of the will. I have been presented with the usual time-table for the first school year. It consists of:

Then:

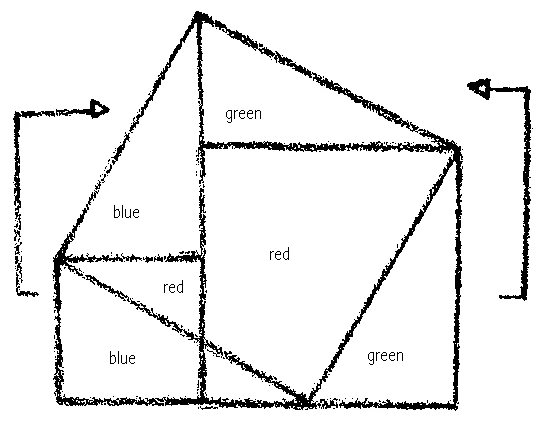

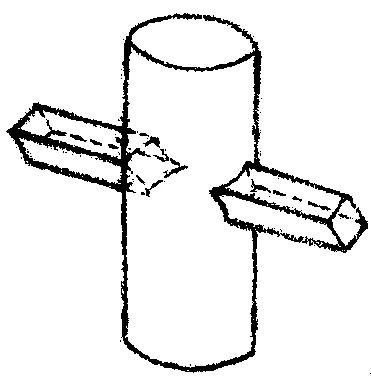

We shall not be guilty of this, for we should then sin too gravely against the well-being of the growing child. But we shall arrange, as far as ever it is in our power, for the singing and music and the gymnastics and Eurhythmy to be in the afternoon, and the rest in the morning, and we shall take, in moderation—until we think they have had enough—singing and music and gymnastics and Eurhythmy with the children in the afternoon. For to devote one hour a week to these subjects is quite ludicrous. That alone proves to you how the whole of teaching is now directed towards the intellect. In the first year in the elementary school we are concerned, after all, with six-year-old children or with children at the most a few months over six. With such children you can quite well study the elements of painting and drawing, of music, and even of gymnastics and Eurhythmy; but if you take religion with them in the modern manner you do not teach them religion at all; you simply train their memory and that is the best that can be said about it. For it is absolutely senseless to talk to children of six to seven of ideas which play a part in religion. They can only be stamped on his memory. Memory training, of course, is quite good, but one must be aware that it here involves introducing the child to all kinds of things which have no meaning for the child at this age. Another feature of the time-table for the first year will provoke us to an opinion different from the usual one, at least in practice. This feature reappears in the second year in a quite peculiar guise, even as a separate subject, as Schönschreiben (literally, pretty writing = calligraphy). In evolving writing from “painting-drawing” we shall obviously not need to cultivate “ugly writing” and “pretty writing” as separate subjects. We shall take pains to draw no distinction between ugly writing and pretty writing and to arrange all written work—and we shall be able to do this in spite of the outside time-table—so that the child always writes beautifully, as beautifully as he can, never suggesting to him the distinction between good writing and bad writing. And if we take pains to tell the child stories for a fairly long time, and to let him repeat them, and pay attention all the time to correct speaking on our part, we shall only need to take spelling at first from the point of view of correcting mistakes. That is, we shall not need to introduce correct writing, Rechtschreiben (spelling), and incorrect writing as two separate branches of the writing lesson. You see in this connection we must naturally pay great attention to our own accuracy. This is especially difficult for us Austrians in teaching. For in Austria, besides the two languages, the dialect and the educated everyday speech, there was a third. This was the specific “Austrian School Language.” In this all long vowels were pronounced short and all short vowels long, and whereas the dialect quite correctly talked of “Die Sonne” (the sun), the Austrian school language did not say “Die Sonne” but “Die Sohne,” and this habit of talking becomes involuntary; one is constantly relapsing into it, as a cat lands on his paws. But it is very unsettling for the teacher too. The further one travels from north to south the more does one sink in the slough of this evil. It rages most virulently in Southern Austria. The dialect talks rightly of “Der SÅ«Å«n”; the school language teaches us to say “Der Son.” So that we say “Der Son” for a boy and “Die Sohne” for what shines in the sky. That is only the most extreme case. But if we take care, in telling stories, to keep all really long sounds long and all short ones short, all sharp ones sharp, all drawn-out ones prolonged, and all soft ones soft, and to take notice of the child's pronunciation, and to correct it constantly, so that he speaks correctly, we shall be laying the foundations for correct writing. In the first year we do not need to do much more than lay right foundations. Thus, in dealing with spelling, we do not yet need to let the child write lengthening or shortening signs, as even permitted in the usual school time-table—we can spend as long as we like over speaking, and only in the last instance introduce the various rules of spelling. This is the kind of thing to which we must pay heed when we are concerned with the right treatment of children at the beginning of their school life. The children near the end of the school life, at the age of thirteen to fourteen, come to us maltreated by the intellectual process. The teaching they have received has been too much concerned with the intellect. They have experienced far too few of the benefits of will- and feeling-training. Consequently, we shall have to make up for lost ground, particularly in these last years. We shall have to attempt, whenever opportunity offers, to introduce will and feeling into the exclusively intellectual approach, by transforming much of what the children have absorbed purely intellectually into an appeal to the will and feelings. We can assume at any rate that the children whom we get at this age have learnt, for instance, the theorem of Pythagoras the wrong way, that they have not learnt it in the way we have discussed. The question is how to contrive in this case not only to give the child what he has missed but to give him over and above that, so that certain powers which are already dried up and withered are stimulated afresh as far as they can be revived. So we shall try, for instance, to recall to the child's mind the theorem of Pythagoras. We shall say: “You have learnt it. Can you tell me how it goes? Now you have said the theorem of Pythagoras to me. The square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides.” But it is absolutely certain that the child has not had the experience which learning this should give his soul. So I do something more. I do not only demonstrate the theorem to him in a picture, but I show how it develops. I let him see it in a quite special way. I say: “Now three of you come out here. One of you is to cover this surface with chalk: all of you see that he only uses enough chalk to cover the surface. The next one is to cover this surface with chalk; he will have to take another piece of chalk. The third will cover this, again with another piece of chalk.” And now I say to the boy or girl who has covered the square on the hypotenuse: “You see, you have used just as much chalk as both the others together. You have spread just as much on your square as the other two together, because the square on the hypotenuse is equal to the sum of the squares on the other two sides.” That is, I make it vivid for him by the use of chalk. It sinks deeper still into his soul when he reflects that some of the chalk has been ground down and is no longer on the piece of chalk but is on the board. And now I go on to say: “Look, I will divide the squares; one into sixteen, the other into nine, the other into twenty-five squares. Now I am going to put one of you into the middle of each square, and you are to think that it is a field and you have to dig it up. The children who have worked at the twenty-five little squares in this piece will then have done just as much work as the children who have turned over the piece with sixteen squares and the children who have turned over the piece with nine squares together. But the square on the hypotenuse has been dug up by your labour; you, by your work, have dug up the square on one of the two sides, and you, by your work, have dug up the square on the other side.” In this way I connect the child's will with the theorem of Pythagoras. I connect at least the idea with an exercise rooted significantly in his will in the outside world, and I again bring to life what his cranium had imbibed more or less dead. Now let us suppose the child has already learnt Latin or Greek. I try to make the children not only speak Latin and Greek but listen to one another as well, listen to each systematically when one speaks Latin, another Greek. And I try to make the difference live vividly for them which exists between the nature of the Greek and Latin languages. I should not need to do this in the ordinary course of teaching, for this realization would result of itself with the ideal time-table. But we need it with the children from outside, because the child must feel: when he speaks Greek he really only speaks with the larynx and chest; when he speaks Latin there is something of the whole being accompanying the sound of the language. I must draw the child's attention to this. Then I will point out to him the living quality of French when he speaks that, and how it resembles Latin very closely. When he talks English he almost spits the sounds out. The chest is less active in English than in French. In English a tremendous amount is thrown away and sacrificed. In fact, many syllables are literally spat out before they work. You need not say “spat out” to the children, but make them understand how, in the English language particularly, the word is dying towards its end. You will try like this to emphasize the introduction of the element of articulation into your language teaching with those children of twelve to fourteen whom you have taken over from the schools of to-day.

|

| 294. Practical Course for Teachers: Moral Educative Principles and their Transition to Practice

05 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| These ideas of things must be rooted in feeling during the middle period of the elementary school course, when the instincts are still alive to this feeling of intimacy with the animals, with the plants, and when, after all, even if the experience never emerges into the ordinary light of reasoning consciousness, the child feels himself now a cat, now a wolf, now a lion or an eagle. This identification of oneself now with one animal, now with the other, only occurs up to about the age of nine. |

| 294. Practical Course for Teachers: Moral Educative Principles and their Transition to Practice

05 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Harry Collison Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

If you were to look back at the time-tables which were issued fifty or sixty years ago, you would see that they were comparatively short. A few short sentences summarized the ground to be covered in every school year in the different subjects. The time-tables were at the most two or three or four pages long—all the rest in those days was left to the actual process of teaching itself, for this out of its own powers should stimulate teachers to do the part left to them by the curricula. To-day things are different. To-day the syllabus for the schools has more and more increased. The Official Gazette has become a collection of books. And in this book there is not only a suggestion of what is required, but there are all kinds of instructions as to how things should be taught at school. That is, in the last decades people were on the way to letting State legislation swallow up the theory of education. And perhaps it is an ideal of many a legislator gradually to issue as “Official Publication,” as “Decrees and Regulations” all the material formerly contained in old literary works on pedagogy. The Socialist leaders quite definitely feel this subconscious impulse—however ashamed they may be to admit it; their ideal is to introduce in the form of decrees what was until recently common spiritual property even in the sphere of education. For this reason those of us here who wish to preserve the educational and teaching system from the collapse which has overtaken it under Lenin—and which might overtake Central Europe—must approach the curriculum with a quite different understanding from that in which the ordinary teacher approaches the Official Gazette. This, even in the days of the monarchy and in the days of ordinary democratic Parliamentarianism, he has solemnly studied, but he will study it with feelings of greater obedience if it is sent to his house by his Dictator-Comrades. The potential tyranny of socialism would be felt quite particularly in the sphere of teaching and education. We have had to approach the curriculum differently. That is, it has been incumbent on us to approach this curriculum with an attitude of mind which enabled us really to create it for ourselves at every turn, so that we learnt to tell the needs of all children at any age. Let us put side by side this ideal curriculum and the curriculum at present in use in other schools of Central Europe. This we shall do and we shall have prepared ourselves thoroughly for this estimate if we have really assimilated into our feelings all that we should absorb on the way to an understanding of a curriculum. Here, again, is a very important aspect which is falsely estimated in these days in official pedagogy. I concluded my last lecture1 with a direct talk on the “Morality of Educational Theory;” the moral tendencies which must be the basis of all pedagogy. It will only result in the practice of teaching if the many examples given in modern books on didactics are ignored. These speak of “object lessons.” They are quite sound, and we have referred to the way in which they should be conducted. But we have constantly had to emphasize the fact that these object lessons should never become trivial, that they should never exceed a certain limit. This eternal cross-questioning of the child on self-evident things in the form of object lessons simply extends a pall of weariness over the whole of teaching, and this should not be. And it robs teaching of precisely what I emphasized at the end of my last lecture2 as so necessary: the cultivation of the child's imaginative faculty or the faculty of fantasy. If, for the sake of giving an object lesson, you discuss with the children the shape of any cooking utensil you like to choose, you undermine his imagination. If you describe the shape or origin of a Greek vase, you may do more for his understanding of what he finds around him in daily life. Object lessons, as given to-day, literally stifle the imagination. And you do not do amiss in teaching if you simply remember to leave many things unspoken, so that the child is induced to continue working with his own soul-force on what he has learnt in the lesson. It is not at all a good thing to want to explain everything down to the last dot on the “i.” The child simply leaves the school feeling that he has learnt everything already, and looking out for other things to do. Whereas if you have sown his imagination with seeds of life he remains fascinated by what the lesson offered him and is less ready to be distracted. That our children to-day are such rough tomboys is simply due to the fact that we go in for far too much false object teaching and too little training of the will and the feelings. But in still another respect we really need to identify ourselves quite inwardly in our souls with the curriculum. When you receive a child in the first years at the elementary school he is quite a different being from the same child in the last years of the school course. In his first years he is still very much immersed in his body, he is still very much part of his body. When the child leaves school you must have enabled him to cling no longer to his body with all the fibres of his soul, but to be independent of his body in thinking, feeling, and willing. Try to penetrate rather more deeply into the nature of the growing being and you will find, relatively speaking, particularly when the children have not been spoilt in their very first years, that they still have very sound instincts. They have then not acquired the craving to stuff themselves with sweets and so on. They still have certain sound instincts with regard to their food, as, of course, the animal too, because he is still very much dominated by his body, has very good instincts in the matter of his own nourishment. The animal, just because he is limited to his body, avoids what is hurtful to him. The animal world is not likely to be overrun by any evil like the spreading of alcoholic consumption in the human world. The spread of evils such as alcohol is due to the fact that man is so much a spiritual being that he can become independent of his bodily nature. For physical nature, in its reasonableness, is never tempted to become alcoholic, for instance. Comparatively sound food instincts are active in the first years at school. These cease in the interests of human development with the last years of school life. When puberty comes upon the individual he loses his food-instincts; he must find in his reason a substitute for his earlier instincts. That is why you can still intercept, as it were, the last manifestations of the food and health instincts in the last school years of the growing being. Here you can still steal a march on the last manifestations of the sound food-instincts, of the instinct of growth, etc. Later you can no longer find an inner feeling for the right care of food and health. That is why particularly the last years of the elementary school course should include instruction in nourishment and the care of personal health. Precisely in this connection object lessons should be given. For these object lessons can reinforce the fantasy or imagination quite considerably. Put before the child three different substances; place these before him, or remind him of them, for he has, of course, already seen them: any substance which is composed primarily of starch or sugar, a substance composed primarily of fat, a substance composed primarily of albumen. The child knows these. But remind him that the human body owes its activity primarily to these three constituents. From this explain to him in his last years of school the secrets of nutrition. Then give him an accurate description of the breathing and enlarge on every aspect of nutrition and breathing connected with the care of personal health. You will gain an enormous amount in your education and teaching if you undertake this instruction precisely in these years. At this stage you are just in time to intercept the last instinctive manifestations of the health and food instincts. That is why you can teach the child in these years about the conditions of nutrition and health without making him egoistic for the rest of his life. It is still natural to him to satisfy instinctively the conditions of health and nutrition. That is why he can be talked to about these things and why they still strike a chord in the natural life of the human being and so do not make him egoistical. If the children are not taught in these years about matters of nutrition and health they will have to inform themselves later from reading or from other people. What the child learns later, after puberty, about matters of nutrition and health, makes him egoistic. It cannot but produce egoism. If you read about nutrition in physiology, if you read a synopsis of rules about the care of the health, in the very nature of the case this information makes you more egoistic than you were before. This egoism, which continually proceeds from a rationalized knowledge of how to take personal care of oneself, has to be combated by morality. If we had not to care for ourselves physically we should not need to have a morality of the soul. But the human being is less exposed to the dangers of egoism in later life if he is instructed in nutrition and health in his last years at the elementary school, where the teaching is concerned with questions of nutrition and health rules, and not with egoism—but with what is natural to man. You see what very far-reaching problems of life are involved in teaching a particular thing at the right moment. You really provide for the whole of his life if you teach a child what is right at his particular age. Of course, if one could imbue children of seven or eight with precepts of nutrition, with precepts of health, that would be the best way of all. They would then absorb these rules of nutrition and health in the most unegoistic way, for they are hardly aware at that moment that the rules refer to themselves. They would see themselves as objects, not as subjects. But they cannot understand it so early. Their power of judgement is not yet sufficiently developed to be able to understand it. For this reason you cannot take rules for nutrition and health at this age, and you must save them up for the last school years, when the fire of the inner instinct of food and health is already dying down, and when, in contrast to these dying instincts, there has already emerged the power to comprehend what comes into consideration. At every turn it is possible to intermingle for the older children some reference to rules of health and nutrition. In natural history, in physics, in the lessons which expand geography to its full scope, even in history lessons, every moment lends itself to an opportunity of instruction in dietetics and health. You will see from this that we do not need to accept it as a subject in the school time-table, but that much of our teaching must contain such vitality that it absorbs this with it. If we have a right feeling for what the child is to learn—then the child himself, or the community of children in school, will remind us every day of what we have to introduce into the rest of our teaching. And for this purpose we have to cultivate and practise, because we are teachers, a certain alertness of mind. If we are drilled as specialists in geography or history we shall not develop this mental alertness, for then we are exclusively concerned, from the beginning of the history lesson to the end of the history lesson, with teaching history. And then there can come into play those extraordinarily unnatural conditions whose injurious effects on life are not by any means fully appreciated. It is profoundly true that we do the human being a service, and one that discourages his egoism, when we teach him the rules of dietetics and health, as I have explained, in the last years at the elementary school. But here, too, it is possible to refer to many aspects which permeate the whole of teaching with feeling. And if you attach a certain amount of feeling to every step of your teaching, the results at which you are aiming will persist throughout life. But if in the last years at the elementary school you only teach things of interest to the reason, to the intellect, very little lasting impression will be made. You will have to permeate your own self with feeling whenever you give something to the children in the years from twelve to fourteen. You must try to teach, not only graphically, but with vivid feeling, geography, history, natural history, in the last school years. Imagination or fantasy is not enough without feeling. Now in actual fact the curriculum for the elementary school (aged seven to fourteen) falls into three distinct periods which we have traced: first, up to nine years of age, when we introduce to the growing child chiefly conventionalities, writing, reading; then up to twelve, when we introduce to him the uses of this conventionality, and on the other hand to all learning based on the individual power of judgement. And you have seen that into this school period we put the study of animals, and nature-study, because the individual at this stage still has a certain instinctive feeling for the relationships here involved. I laid down lines for you on which to develop, from the cuttle-fish, the mouse, the lamb, and the human being, a feeling of the relationship of man with the whole of the world of nature. We have taken great pains, too—and I hope not in vain, for they will flower and come to fruition in the teaching of botany—to develop man's relation to the plant world. These ideas of things must be rooted in feeling during the middle period of the elementary school course, when the instincts are still alive to this feeling of intimacy with the animals, with the plants, and when, after all, even if the experience never emerges into the ordinary light of reasoning consciousness, the child feels himself now a cat, now a wolf, now a lion or an eagle. This identification of oneself now with one animal, now with the other, only occurs up to about the age of nine. Before this age it is even more profound, but it cannot be used, because the power to grasp it consciously is non-existent. If children are very precocious and talk a great deal about themselves when they are still only four or five, their comparisons of themselves with the eagle, with the mouse, etc., are very common indeed. But if we start at the ninth year to teach natural history on the lines I have suggested, we come upon a good deal of the child's instinctive feeling of relationship with animals. Later this instinctive feeling ripens into a feeling of relationship with the plant world. Therefore, first of all the natural history of the animal kingdom, then the natural history of the plant kingdom. We leave the minerals till the last because they require almost exclusively the power of judgement. So it is in accordance with human nature to arrange the curriculum as I have suggested. The intermediate school period, from eight to eleven, presents a fine balance between the instincts and the powers of discernment. We can always assume that the child will respond intelligently if we rely on a certain instinctive understanding, if we are not—especially in natural history and botany—too obvious. We must avoid drawing external analogies particularly with the plant world, for that is really contrary to natural feeling. Natural feeling is itself predisposed to seek psychic qualities in plants; not the external physical form of man in this tree or that, but soul-relations such as we tried to discover in the plant system.3 And the actual power of discernment, the rational, intellectual comprehension of the human being which can be relied on, belongs to the last school period. For this reason we employ precisely the twelfth year in the child's life, when he is gravitating in the direction of the power of discernment, for merging this power of judgement in the activities still partly prompted by instinct, but already very thickly overlaid with discerning power. These are, as it were, the twilight instincts of the soul, which we must overcome by the power of judgement. At this stage it must be remembered that man has an instinct for gain, for profiteering, for the principle of discount, etc., which appeals to the instincts. But we must be sure to impose the power of discernment very forcibly upon this, and consequently we must use this stage of development for studying the relations existing between calculation and the circulation of commodities and finance, that is, for doing percentage sums, interest sums, discount sums, etc. It is very important not to give the child these ideas too late, for that would really be appealing to his egoism. We are not yet reckoning on his egoism if we teach him at about the age of twelve to grasp to some extent the principle of promissory notes and so on, commercial calculations, etc. Actual book-keeping could be studied later; this already requires more intelligence. But it is very important to bring out these ideas at this stage. For the inner selfish appetite for interest, bills of exchange, promissory notes, and so on, is not yet awake in the child at this tender age. These things are more serious in the commercial schools when he is older. You must absorb these facts quite completely into your being as instructors, as teachers. Try not to do too much, whatever your inclination may be, let us say, in describing plants. Try to teach about plants so that a great deal is left to the child's imagination, that the child can still imagine for himself, in terms of his own feeling, the psychic relations prevailing between the human soul and the plant world. The person who enthuses too freely on object lessons does not know that there are things to be taught which cannot be studied externally. And when people try to teach the child by object lessons things which ought only to be taught through moral influence and through the feelings, this very object teaching does him harm. We must never forget, you see, that mere observation and illustration are a very pronounced by-product of the materialistic spirit of our age. Naturally, observation must be cultivated in its proper place, but you must not apply the method when it would only spoil the intimate relation between the child and the world in the sphere of his imaginative mind.

|

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Five

26 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| For example, in the melancholic temperament the predominance of the I passes into the predominance of the physical body, and in a choleric person it even cuts across inheritance and passes from the mother element to the father element, because the preponderance of the astral passes over into a preponderance of the I. |

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Five

26 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

RUDOLF STEINER: It is most important that, along with all our other work, we should cultivate clear articulation. This has a kind of influence, a certain effect. I have here some sentences that I formulated for another occasion; they have no especially profound meaning, but are constructed so that the speech organs are activated in every kind of movement, organically. I would like you to pass these sentences around and repeat them in turn without embarrassment so that by constant practice they may make our speech organs flexible; we can have these organs do gymnastics, so to speak. Mrs. Steiner will say the sentences first as it should be done artistically, and I will ask each one of you to repeat them after her. These sentences are not composed according to sense and meaning, but in order to “do gymnastics” with the speech organs.1

The N is constantly repeated, but in different combinations of letters, and so the speech organ can do the right gymnastic exercises. At one point two Ns come together; you must stop longer over the first N in “on nimble.”

In this way you can activate the speech organs with the right gymnastics. I would recommend that you take particular care to find your way into the very forms of the sounds and the forms of the syllables; see that you really grow into these forms, so that you consciously speak each sound, that you lift each sound into consciousness. It is a common weakness in speech that people just glide over the sounds, whereas speech is there to be understood. It would even be better to first bring an element of caricature into your speech by emphasizing syllables that should not be emphasized at all. Actors, for example, practice saying friendly instead of friendly! You must pronounce each letter consciously. It would even be good for you to do something like Demosthenes did, though perhaps not regularly. You know that, when he could not make any progress with his speaking, he put pebbles on his tongue and through practice strengthened his voice to the degree that it could be heard over a rushing river; this he did to acquire a delivery that the Athenians could hear. I will now ask Miss B. to introduce the question of temperaments. Since the individual child must be our primary consideration in teaching, it is proper that we study the basis of the temperaments with the maximum care. Naturally when we have a class it is not possible to treat each child individually. But you can give much individual treatment by having on one side, let’s say, the phlegmatics and melancholics, and the sanguine and choleric children on the other side; you can have them take part in a lively interchange, turning now to the group of one temperament, and then calling on another group for answers, saying this to one group and that to another. In this way individualization happens on its own in the class. A comprehensive picture was presented of the temperaments and their treatment. RUDOLF STEINER: You have given a good account of what was spoken of in our conversations together on this subject. But you may be going too far when you assert, with regard to the melancholic temperament, that it has a decided inclination toward piety. There is only one little word lacking: “often.” It is also just possible that the melancholic disposition in children is rooted in pronounced egoism, and in no way has a religious tendency. With adults you can leave out the little word “often,” but in young children the melancholic element often masks a pronounced egoism. Melancholic children are often dependent on atmospheric conditions; the weather often effects the melancholic temperament. The sanguine children are also dependent on atmospheric conditions, but more in their moods, in the soul, whereas the melancholic children are affected more unconsciously by the weather in the physical body. If I were to go into this question in detail from the standpoint of spiritual science, I would have to show you how the childish temperament is actually connected with karma, how in the child’s temperament something really appears that could be described as the consequence of experiences in previous lives on Earth. Let’s take the concrete example of a man who is obliged in one life to be very interested in himself. He is lonely and is thus forced to be interested in himself. Because he is frequently absorbed in himself, the force of circumstances causes him to be inclined to unite his soul very closely with the structure of his physical body, and in the next incarnation he brings with him a bodily nature keenly alive to the conditions of the outer world. He becomes a sanguine individual. Thus, it can happen that when someone has been compelled to live alone in one incarnation, which would have retarded the person’s progress, this is adjusted in the next life through becoming a sanguine, with the ability to notice everything in the surroundings. We must not view karma from a moral but from a causal perspective. When a child is properly educated, it may be of great benefit to the child’s life to be a sanguine, capable of observing the outer world. Temperament is connected, to a remarkable degree, with the whole life and soul of a person’s previous incarnation. Dr. Steiner was asked to explain the changes of temperaments that can occur during life, from youth to maturity. RUDOLF STEINER: If you remember a course of lectures that I once gave in Cassel about the Gospel of St. John, you will recall the remarks I made concerning the relationship of a child to his or her parents.2 It was stated there that the father-principle works very strongly in the physical body and the I, and that the mother-principle predominates in the etheric and astral bodies. Goethe divined this truth when he wrote the beautiful words:

There is extraordinary wisdom in these words. What lives in the human being is mixed and mingled in a remarkable way. Humankind is an extremely complicated being. A definite relationship exists in human beings between the I and the physical body, and again a relationship between the etheric body and the astral body. Thus, the predominance of one can pass over into the predominance of another during the course of life. For example, in the melancholic temperament the predominance of the I passes into the predominance of the physical body, and in a choleric person it even cuts across inheritance and passes from the mother element to the father element, because the preponderance of the astral passes over into a preponderance of the I. In the melancholic temperament the I predominates in the child, the physical body in the adult. In the sanguine temperament the etheric body predominates in the child and the astral body in the adult. In the phlegmatic temperament the physical body predominates in the child and the etheric body in the adult. In the choleric temperament the astral body predominates in the child, the I in the adult. But you can only arrive at a true view of such things when you strictly remember that you cannot arrange them in a tabulated form, and the higher you come into spiritual regions, the less this will be possible. The observation was expressed that a similar change can be found in the sequence of names of the characters in The Guardian of the Threshold and The Souls’ Awakening.3 RUDOLF STEINER: There is a change there that is definitely in accordance with the facts; these Mystery Plays must be taken theoretically as little as possible. I cannot say anything if the question is put theoretically, because I have always had these characters before me just as they are, purely objectively. They have all been taken from real life. Recently, on another occasion, I said here that Felix Balde4 was a real person living in Trumau, and the old shoemaker who had known the archetype of Felix is called Scharinger, from Münchendorf. Felix still lives in the tradition of the village there. In the same way all these characters whom you find in my Mystery Plays are actual individual personalities. Question: In speaking of a folk temperament can you also speak of someone as belonging to the temperament of one’s nation? And a further question: Is the folk temperament expressed in the language? RUDOLF STEINER: What you said first is right, but your second suggestion is not quite correct. It is possible to speak of a folk temperament in a real sense. Nations really have their own temperaments, but the individual can very well rise above the national temperament; one is not necessarily predisposed to it. You must be careful not to identify the individuality of the particular person with the temperament of his whole nation. For example, it would be wrong to identify the individual Russian of today with the temperament of the Russian nation. The latter would be melancholic while the individual Russian of today is inclined to be sanguine. The quality of the national temperament is expressed in the various languages, so one could certainly say that the language of one nation is like this, and the language of another nation is like that. It is true to say that the English language is thoroughly phlegmatic and Greek exceptionally sanguine. Such things can be said as indications of real facts. The German language, being two-sided in nature, has very strongly melancholic and also very strongly sanguine characteristics. You can see this when the German language appears in its original form, particularly in the language of philosophy. Let me remind you of the wonderful quality of Fichte’s philosophical language or of some passages in Hegel’s Aesthetics, where you find the fundamental character of German language expressed with unusual clarity. The Italian folk-spirit has a special relationship to air, the French a special connection with fluids, the English and American, especially the English, with the solid earth, the American even with the sub-earthly—that is, with earth magnetism and earth electricity. Then we have the Russian who is connected with the light—that is, with earth’s light that rays back from plants. The German folk-spirit is connected with warmth, and you see at once that this has a double character—inner and outer, warmth of the blood and warmth of the atmosphere. Here again you find a polaric character even in the distribution of these elementary conditions. You see this polarity at once—this cleavage in the German nature, which can be found there in everything. Question: Should the children know anything about this classification according to temperament? RUDOLF STEINER: This is something that must be kept from the children. Much depends on whether the teacher has the right and tactful feeling about what should be kept hidden. The purpose of all these things we have spoken of here is to give the teacher authority. The teacher who doesn’t use discretion in what to say cannot be successful. Students should not be seated according to their attainments, and you will find it advantageous to refuse requests from children to sit together. Question: Is there a connection between the temperaments and the choice of foreign languages for the different temperaments of the children? RUDOLF STEINER: Theoretically that would be correct, but it would not be advisable to consider it given current conditions. It will never be possible to be guided only by what is right according to the child’s disposition; we have to remember also that children must make their way in the world, and we have to give them what they need to do that. If in the near future, for example, it appeared as if a great many German children had no aptitude for learning English, it would not be good to give in to this weakness. Just those who show a weakness of this kind may be the first to need to know English. There was a discussion on the task given the previous day: to consider the case of a whole class that, incited by one child, was guilty of very bad behavior; for example, they had been spitting on the ceiling. Some views were expressed on this matter. RUDOLF STEINER interjected various remarks: It is a very practical method to wait for something like this to wear out, so that the children stop doing it on their own. You should always be able to distinguish whether something is done out of malice or high spirits. One thing I would like to say: Even the best teacher will have naughtiness in the class, but if a whole class takes part it is usually the teacher’s fault. If it isn’t the teacher’s fault, you will always find that a group of children are on the teacher’s side and will be a support. Only when the teacher has failed will the whole class take part in insubordination. If there has been any damage, then of course it is proper that it should be corrected, and the children themselves must do this—not by paying for it, but with their own hands. You could use a Sunday, or even two or three Sundays to repair any damage. And remember, humor is also a good method of reducing things to an absurdity, especially minor faults. I gave you this problem to think on to help you see how to tackle something that occurs when one child incites the others. To demonstrate where the crux of the matter lies, I will tell you a story of something that actually occurred. In a class where things of this kind often happened, and where the teachers could not cope with them, one of the boys between ten and twelve years old went up to the front during the interval between two lessons and said, “Ladies and gentlemen! Aren’t you ashamed of always doing things like this, you good-fornothings? Just remember, you would all remain completely stupid if the teachers didn’t teach you anything.” This had the most wonderful effect. We can learn something from this episode: When a large proportion of the class does something like this because of the instigation of one or more of the children, it may very well happen that, also through the influence of a few, order may be restored. If a few children have been instigators there will be others, two or three perhaps, who express disapproval. There are almost always leaders among the children, so the teacher should pick out two or three considered suitable and arrange a conversation with them. The teacher would have to make it clear that behavior of this kind makes teaching impossible, and that they should recognize this and make their influence felt in the class. These children will then have just as much influence as the instigators, and they can make things clear to their classmates. In any situation like this you must consider how the children affect one another. The most important thing here is that you should evoke feelings that will lead them away from naughtiness. A harsh punishment on the part of the teacher would only cause fear and so on. It would never inspire the children to do better. The teacher must remain as calm as possible and adopt an objective attitude. That does not mean lessening the teacher’s own authority. The teacher could certainly be the one to say, “Without your teachers you would learn nothing and remain stupid.” But the teacher should allow the correction be carried out by the other children, leaving it to them to make their schoolmates feel ashamed. We thus appeal to feelings rather than to judgment. But when the whole class is repeatedly against the teacher, then the fault must be looked for in the teacher. Most naughtiness arises because the children are bored and lack a relationship with their teacher. When a fault is not too serious it can certainly be very good for the teacher to do just what the pupils are doing—to say, for example, when the pupils are grumbling, “Well I can certainly grumble too!” In this way the matter is treated homeopathically, as it were. Homeopathic treatment is excellent for moral education. It’s also a good way to divert the children’s attention to something else (although I would never appeal to their ambition). In general, however, we seldom have to complain of such misdemeanors. Whenever you allow mischievousness of this kind to be corrected by other children in the class, you work on the feelings to reestablish weakened authority. When another pupil stresses that gratitude must be felt toward the teacher, then the respect for authority will be restored again. It is important to choose the right children; you must know your class and pick those suited to the task. If I taught a class I could venture to do this. I would try to find the ringleader, whom I would compel to denounce, as much as possible, such conduct, to say as many bad things about it as possible, and I would ignore the fact that it was this student who had done it. I would then bring the matter quickly to a close so that a sense of uncertainty would be left in the minds of the children, and you will come to see that much can be gained from this element of uncertainty. And to make one of the rascals involved describe the incident correctly and objectively will not in any way lead to hypocrisy. I would consider any actual punishment superfluous, even harmful. The essential thing is to arouse a feeling for the objective damage that has been caused and the necessity of correcting it. If teaching time has been lost in dealing with this matter, then it must be made good after school hours, not as a punishment but simply to make up the time lost. I will now present a problem of a more psychological nature: if you have some rather unhealthy “goody-goodies” in the class—children who try to curry favor in various ways, who have a habit of continually coming to the teacher about this, that, and the other, how would you treat them? Of course you can treat the matter extremely simply. You could say: I am simply not going to bother with them. But then this peculiarity will be turned into other channels: these “good” children will gradually become a harmful element in the class.

|

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Eight

29 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| When the parents agree to try to provide the child with a really good wholesome diet, however—omitting the items of food mentioned above—they might even cut down on the meat for awhile and give the child plenty of vegetables and nourishing salads. You will then notice that, through a diet like this, the child will make considerable gains in ability. |

| 295. Discussions with Teachers: Discussion Eight

29 Aug 1919, Stuttgart Tr. Helen Fox, Catherine E. Creeger Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

Speech Exercise:

RUDOLF STEINER: The first four sentences have a ring of expectation, and the last line is a complete fulfillment of the first four. Now let’s return to the other speech exercise:

RUDOLF STEINER: You can learn a great deal from this. And now we will repeat the sentence:

RUDOLF STEINER: Also there is a similar exercise I would like to point out that has more feeling in it. It consists of four lines, which I will dictate to you later. The touch of feeling should be expressed more in the first line:

RUDOLF STEINER: You must imagine that you have a green frog in front of you, and it is looking at you with lips apart, with its mouth wide open, and you speak to the frog in the words of the last three lines. In the first line, however, you tell it to lisp the lovely lyrics “Lulling leader limply.” This line must be spoken with humorous feeling; you really expect this of the frog. And now I will read you a piece of prose, one of Lessing’s fables.1