| 305. Spiritual Ground of Education: Body Viewed from the Spirit

19 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Daphne Harwood Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| Such is the fine and delicate knowledge that one must have in order to educate in a proper way. This is the manner of a child's life up to the changing of the teeth. It is entirely given up to what its organism has absorbed from the adults around it. |

| We must say to ourselves with regard to the child: clever a teacher or educator may be, the child reveals to us in his life infinitely significant spiritual and divine things. |

| Love for what we have to do with the child. Respect for the freedom of the child—a freedom we must not endanger; for it is to this freedom we educate the child, that he may stand in freedom in the world at our side. |

| 305. Spiritual Ground of Education: Body Viewed from the Spirit

19 Aug 1922, Oxford Translated by Daphne Harwood Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

It might perhaps appear as if the art of education described in these lectures would lead away from practical life into some remote, purely spiritual region: as though this art of education laid too much stress on the purely spiritual domain. From what I have said so far in describing the spiritual foundation of the education, this might appear to be the case. But this is only in appearance. For in reality the art of education which arises from this philosophy has the most practical objects in view. Thus it should be realised that the main object of speaking of spiritual facts here is to answer the educational question: how can we best develop the physical organism in childhood and youth? That a spiritual philosophy should consider firstly the development of the physical organism may seem to be a fundamental contradiction. The treatment of my theme in the next few days, however, will do more towards dispelling this contradiction than any abstract statements I could make at the outset. To-day, I would merely like to say that when one speaks on educational questions at the present day one finds oneself in a peculiar situation. For if one sees much that needs reforming in education, it is as much as to say that one is not satisfied with one's own education. One implies that one's own education has been exceedingly bad. And yet, as a product of this very bad education, of this education in which one finds so much to criticise—for other-wise why be a reformer?—one sets up to know the right way to educate! This is the first thing that involves a contradiction. The second thing is one which gives one a slight feeling of shame in face of the audience when speaking on education,—for one realises that one is speaking of what education ought to be and how it must be different from present day practice. So that it amounts to saying: you are all badly educated. And yet one is appealing to those who are badly educated to bring about a better education. One assumes that both the speaker and the audience know very well what good education should be in spite of the fact that they have been exceedingly badly educated. Now this is a contradiction, but it is one which life itself presents us, and it can really only be solved by the view of education which is here being described. For one can perfectly well know what is the matter with education and in what respects it should be improved, just as one can know that a picture is well painted without possessing the faintest capacity for painting a picture oneself. You can consider yourself capable of appreciating the merits of a picture by Raphael without thinking yourself capable of painting a Raphael picture. In fact it would be a good thing to-day if people would think like this. But they are not content with merely knowing, where education is concerned, they claim straightaway to know how to educate; as though someone who is no painter and could not possibly become a painter, should set up to show how a badly painted picture should be painted well. Now it is here contended that it is not enough to know what good education is but that one must have a grasp of the technique and detail of educational art, one must acquire practical skill. And for this, knowledge and understanding are necessary. Hence yesterday I tried to explain the elementary principles of guidance in this ability, and I will now continue this review. It is easy to say man undergoes development during his lifetime, and that he develops in successive stages. But this is not enough. Yesterday we saw that man is a three-fold being: that his thinking is entirely bound up physically with the nerve-senses-system of his organism, his feeling is bound up with the rhythmic system, particularly the breathing and circulation system, and that his will is bound up with the system of movement and metabolism. The development of these three systems in man is not alike. Throughout the different epochs of life they develop in different ways. During the first epoch which extends to the change of teeth—as I have repeatedly stated—the child is entirely sense organ, entirely head, and all its development proceeds from the nerve-senses system. The nerve-senses system permeates the whole organism; and all impressions of the outside world affect the whole organism, work right through it, just as, later in life, light acts upon the eye, In other words, in an adult light comes to a standstill in the eye, and only sends the idea of itself, the concept of light, into the organism. In a child it is as if every little blood corpuscle were inwardly illumined, were transfused with light—to express it in a somewhat exaggerated and pictorial way. The child is as yet entirely exposed to those etheric essences, (effluvia), which in later life we arrest at the surface of our bodies, in the sense organs,—while we develop inwardly something of an entirely different nature. Thus a child is exposed to sense impressions in a far greater degree than is the adult. Observe a concrete instance of this: take a person who has charge of the nurture of a very young child, perhaps a tiny baby; a person with his own world of inner experience. Let us suppose the person m charge of the child is a heavy hearted being, one to whom life has brought sorrow. In the mature man the physical consequences of the experiences he has been through will not be obvious, but will leave only faint traces. When we are sad our mouth is always a little dry. And when sadness becomes a habitual and continuous state, the sorrowful person goes about with dry mouth, with parched tongue, with a bitter taste in the mouth and even a chronic catarrh. In the adult these physical conditions are merely faint undertones of life. The child who is growing up in the company of the adult is an imitator; he models himself entirely on the physiognomy of the adult, on what he perceives:—on the adult's sad manner of speaking, his sad feelings. For there is a subtle interplay betwixt child and adult, an interplay of imponderables. When we have an inner sadness and all its physical consequences, the child being an imitator, takes up these physical effects through inward gestures: through an inward mimicry he takes up the parched tongue, the bitter taste in the mouth; and this—as I pointed out yesterday—flows through the whole organism. He absorbs the paleness of the long sad face of the adult. The child cannot imitate the soul content of the sorrow, but it imitates the physical effects of the sorrow. And the result is that, since the spirit is still working into the child's whole organism, his whole organism will be permeated in such a manner as to build up his organs in accordance with the physical effects which he has taken up into himself. Thus the very condition of the child's organism will make a sad being of him. In later life he will have a particular aptitude for perceiving everything that is sad or sorrowful. Such is the fine and delicate knowledge that one must have in order to educate in a proper way. This is the manner of a child's life up to the changing of the teeth. It is entirely given up to what its organism has absorbed from the adults around it. And the inner conflict taking place here is only perceptible to spiritual science; this struggle which goes on can only be described as the fight between inherited characteristics and adaptation to environment. We are born with certain inherited characteristics.—This can be seen by anybody who has the opportunity of observing a child during its first weeks or years. Science has produced an extensive teaching on this subject.—But the child has more and more to adapt itself to the world. Little by little he must transform his inherited characteristics until he is not merely the bearer of a heredity from his parents and ancestors, but is open in his senses and soul and spirit to receive what goes on at large in his environment. Otherwise he would become an egotistic man, a man who only wants what accords with his inherited characteristics. Now we have to educate men to be susceptible to all that goes on in the world: men who each time they see a new thing can bring their judgment and their feelings to meet this new thing. We must not educate men to be selfishly shut up within themselves, we must educate men to meet the world with a free and open mind, and to act in accordance with the demands of the world. This attitude is the natural outcome of such a position as I described yesterday. Thus we must observe in all its details the inner struggle which takes place during the child's early years between heredity and adaptation to environment. Try to study with the utmost human devotion the wonderful process that goes on where the first teeth are replaced by the second. The first teeth are an inherited thing. They seem almost unsuitable for the outer world. They are inherited. Gradually above each inherited tooth another tooth is formed. In the modelling of this tooth the form of the first tooth is made use of, but the form of the second tooth, which is permanent, is a thing adapted to the world. I always refer to this process of the teeth as characteristic of this particular period of life, up to the seventh year. But it is only one symptom. For what takes place in the case of the teeth conspicuously, because the teeth are hard organs, is taking place throughout the organism. When we are born into the world we bear within us an inherited organism. In the course of the first seven years of our life we model a new organism over it. The whole process is physical. But while it is physical it is the deed of the spirit and soul within the child. And we who stand at the child's side must endeavour so to guide this soul and spirit that it goes with and not against the health of the organism. We must therefore know what spiritual and psychic processes have to take place for the child to be able to model a healthy organism in the stead of the inherited organism. We must know and do a spiritual thing in order to promote a physical thing. And now, if we follow up what I said to you to-day in the introduction we come to something else. Suppose that as a teacher or educator we enter a classroom. Now we must never think that we are the most intelligent of human beings, men at the summit of human intelligence—that, indeed, would mean that we were very bad teachers. We really should think ourselves only comparatively intelligent. This is a sounder state of mind than the other. Now with this state of consciousness we enter the classroom. But as we go in we must say to ourselves: there may be among the children a very intelligent being, one who in later life will be far more intelligent than we. Now if we, who are only comparatively intelligent, should bring him up to be only as intelligent as ourselves, we should be making him a copy of ourselves. That would be quite wrong. For the right thing would be so to educate this very intelligent individual that he may grow up to be far more intelligent than we are ourselves or ever could be. Now this means that there is something in a man which we may not touch, something we must regard with sensitive reverence if we are to exercise the art of education rightly. And this is part of the answer to the question I asked. Often, in earlier life, we know exceedingly well what we ought to do—only we cannot carry it out. We feel unequal to it. What it is that prevents us from doing what we ought to do is generally very obscure. It is always some condition of the physical organism,—for example, an imitated disposition to sadness such as I spoke of. The organism has incorporated this, it has become habitual. We want to do some-thing which does not suit an organism with a bent to sadness. Yet such is our organism. In us we have the effects of the parched tongue and bitter taste from our childhood, now we want to do something quite different and we feel difficulty. If we realise the full import of this we shall say to our-selves: the main task of the teacher or educator is to bring up the body to be as healthy as it possibly can be; this means, to use every spiritual measure to ensure that in later life a man's body shall give the least possible hindrance to the will of his spirit. If we make this our purpose in school we can develop the powers which lead to an education for freedom. The extent to which spiritual education works healthily upon the physical organism, and thus upon man as a whole, can be seen particularly well when the great range of facts provided by our magnificent modern natural science is brought together and co-ordinated in a manner only possible to spiritual science. It then becomes apparent how one can work in the spirit for the healing of man. To take a single instance. The English doctor, Dr. Clifford Albert, has said a very significant thing about the influence of grieving and sadness in human beings upon the development of their digestive organs, and—in particular—upon the kidneys. People who have a lot of trouble and grief in life show signs after a time of malformation of the kidneys, deformed kidneys. This has been very finely demonstrated by the physician Dr. Clifford Albert. That is a finding of natural science. The important thing is that one should know how to use a scientific discovery like this in educational practice. One must know, as a teacher or educator, that if one lets the child imitate one's own sorrow and grief, then through one's sorrowful bearing one is damaging the child's digestive system to the utmost degree. In so far as we let our sorrow overflow into the child we damage its digestive system. You see, this is the tragedy of this materialistic age, that it discovers many physical facts,—if you take the external aspect, but it lacks the connections between them;—it is this very materialistic science which fails to perceive the significance of the physical and material. What spiritual science can do is to show, on all hands, how spirit and what is spiritual work within the physical realm. Then instead of yearning in dreamy mysticism for castles in the clouds, one will be able to follow up the spirit in all its details and singular workings. For one is a spiritual being only when one recognises spirit as that which creates, as that which everywhere works upon and shapes the material:—not when one worships some abstract spirit in the clouds like a mystic, and for the rest, holds matter to be merely the concern of the material world. Hence it is actually a matter of coming to realise how in a young child, up to the seventh year, nerve-senses activity, rhythmic breathing and circulation activity, and the activity of movement and metabolism are everywhere interplaying:—only the nerve-senses activity predominates, it has the upper hand; and thus the nerve-senses activity in a child always affects his breathing. If a child has to look at a face that is furrowed with grief, this affects his senses to begin with; but it reacts upon the manner of his breathing, and hence in turn, upon his whole movement and metabolic system. If we take a child after the change of teeth, that is after about the seventh year, we find the nerve-senses system no longer preponderating; this has now become more separate, more turned towards the outer world. In a child between the change of teeth and puberty it is the rhythmic system which preponderates, which has the upper hand. And it is most important that this should be borne in mind in the primary school. For in the primary school we have children between the change of teeth and puberty. Hence we must know here: the essential thing is to work with the child's rhythmic system, and everything which works upon some-thing other than the rhythmic system is wrong. But now what is it that works upon the rhythmic system? It is art that works upon the rhythmic system, everything that is conveyed in artistic form. Consider how much everything to do with music is connected with the rhythmic system. Music is nothing else but rhythm carried over into the rhythmic system of the human being himself. The inner man himself becomes a lyre, the inner man becomes a violin. His whole rhythmic system reproduces what the violin has played, what has sounded from the piano. And as in the case of music, so it is also, in a finer, more delicate way, in the case of plastic art, and of painting. Colour harmonies and colour melodies also are reproduced and revived as inner rhythmic processes in the inner man. If our instruction is to be truly educational we must know that throughout this period everything that the child is taught must be conveyed in an artistic form. According to Waldorf School principles the first consideration in the elementary school period is to compose all lessons in a way that appeals to the child's rhythmic system. How little this is regarded to-day can be seen from the number of excellent scientific observations which are continuously being accumulated and which sin directly against this appeal to the rhythmic system. Research is carried on in experimental psychology to find out how soon a child will tire in one activity or another; and the instruction must take account of this fatigue. This is all very fine, splendid, as long as one does not think spiritually. But if one thinks spiritually the matter appears in a very different light. The experiments can still be made. They are very good. Nothing is said here against the excellence of natural science. But one says: if the child shows a certain degree of fatigue in the period between its change of teeth and puberty, you have not been appealing, as you should do, to the rhythmic system, but to some other system. For throughout life the rhythmic system never tires. Throughout the whole of life the heart beats night and day. It is in his intellectual system and in his metabolic system that a man becomes tired. When we know that we have to appeal to his rhythmic system we know that what we have to do is to work artistically (Manuscript defective.); and the experiments on fatigue show where we have gone wrong, where we have paid too little attention to the rhythmic system. When we find a child has got overtired we must say to ourselves: How can you contrive to plan your lesson so that the child shall not get tired? It is not that one sets up to condemn the modern age and says: natural science is bad, we must oppose it. The spiritual man has no such intention. He says rather: we need the higher outlook because it is just this that makes it possible to apply the results of natural science to life. If we now turn to the moral aspect, the question is how we can best get the child to develop moral impulses. And here we are dealing with the most important of all educational questions. Now we do not endow a child with moral impulses by giving him commands, by saying: you must do this, this has to be done, this is good,—by wanting to prove to him that a thing is good, and must be done. Or by saying: That is bad, that is wicked, you must not do that,—and by wanting to prove that a certain thing is bad. A child has not as yet the intellectual attitude of an adult towards good and evil, towards the whole world of morality,—he has to grow up to it. And this he will only do on reaching puberty, when the rhythmic system has accomplished its essential task and the intellectual powers are ripe for complete development. Then the human being may experience the satisfaction of forming moral judgment in contact with life itself. We must not engraft moral judgment onto the child. We must so lay the foundation for moral judgment that when the child awakens at puberty he can form his own moral judgment from observation of life. The last way to attain this is to give finite commands to a child. We can achieve it however if we work by examples, or by presenting pictures to the child's imagination: for instance through biographies or descriptions of good men or bad men; or by inventing circumstances which present a picture, an imagination of goodness to the child's mind. For, since the rhythmic system is particularly active in the child during this period, pleasure and displeasure can arise in him, not judgment as to good and evil,—but sympathy with the good which the child beholds presented in an image,—or antipathy to the evil which he beholds so presented. It is not a case of appealing to the child's intellect, of saying ‘Thou shalt’ or ‘Thou shalt not,’ but of fostering aesthetic judgment, so that the child shall begin to take pleasure in goodness, shall feel sympathy when he sees goodness, and feel dislike and antipathy when he beholds evil. This is a very different thing from working on the intellect, by way of precepts formulated by the intellect. For the child will only be awake for such precepts when it is no longer our business to educate him, namely, when he is a man and learns from life itself. And we should not rob the child of the satis-faction of awakening to morality of his own accord. And we shall not do this if we give him the right preparation during the rhythmic period of his life; if we train him to take an aesthetic pleasure in goodness, an aesthetic dislike of evil; that is, if also here, we work through imagery. Otherwise, when the child awakens after puberty he will feel an inward bondage, He will not perhaps realise this bondage consciously, but throughout his subsequent life he will lack the important experience: morality has awakened within me, moral judgment has developed. We cannot attain this inner satisfaction by means of abstract moral instruction, it must be rightly prepared by working in this manner for the child's morality. Thus it is everywhere a case of ‘how’ a thing is done. And we can see this both in that part of life which is concerned with the external world and that part of life concerned with morality: both when we study the realm of nature in the best way, and when we know how best morals can be laid down in, the rhythmic system—in the system of breathing and blood circulation. If we know how to enter with the spirit into what is physical, and if we can come to observe how spirit weaves continuously in the physical, we shall be able to educate in the right way. While a knowledge of man is sought in the erst instance for the art of education and instruction, yet in practice the effect of such a spiritual outlook on the teacher's or educator's state of mind is of the greatest importance. And what this is can best be shown in relation to the attitude of many of our contemporaries. Every age has its shadow side, no doubt, and there is much in past ages we have no wish to revive; nevertheless anyone who can look upon the historical life of man with certain intuitive sense will perceive that in this our own age many men have very little inner joy, on the contrary they are beset by heavy doubts and questions as to destiny. This age has less capacity than any other for deriving answers to its problems from out of the universe, the world at large. Though I may be very unhappy in myself, and with good reason, yet there is always a possibility of finding something in the universe which can counterbalance my unhappiness. But modern man has not the strength to find consolation in a view of the universe when his personal situation makes him downcast. Why is this? Because in his education and development modern man has little opportunity to acquire a feeling of gratitude: gratitude namely that we should be alive at all as human beings within this universe. Rightly speaking all our feelings should take their rise from a fundamental feeling of gratitude that the cosmic world has given us birth and given us a place within itself. A philosophy which concludes with abstract observations and does not flow out in gratitude towards the universe is no complete philosophy. The final chapter of every philosophy, in its effect on human feeling at all events, should be gratitude towards the cosmic powers. This feeling is essential in a teacher and educator, and it should be instinctive in every person who has the nurture of a child entrusted to him. Therefore the first thing of importance to be striven for in spiritual knowledge is the acquiring of thankfulness that a child has been given into our keeping by the universe. In this respect reverence for the child, reverence and thankfulness, are not to be sundered. There is only one attitude towards a child which can give us the right impulse in education and nurture and that is the religious attitude, neither more nor less. We feel religious in regard to many things. A flower in the meadow can make us feel religious when we can take it as the creation of the divine spiritual order of the world. In face of lightning lashes in the clouds we feel religious if we see them in relation to the divine spiritual order of the world. And above all we must feel religious towards the child, for it comes to us from the depths of the universe as the highest manifestation of the nature of the universe, a bringer of tidings as to what the world is. In this mood lies one of the most important impulses of educational technique. Educational technique is of a different nature from the technique devoted to un-spiritual things. Educational technique essentially involves a religious moral impulse in the teacher or educator. Now you will perhaps say: nowadays, although people are so terribly objective in regard to many things—things possibly of less vital importance—nowadays we shall yet find some who will think it a tragic thing that they should have a religious feeling for a child who may turn out to be a ne'er-do-well. But why must I regard it as a tragedy to have a child who turns out a ne'er-do-well?—To-day, as we said before, there are many parents, even in this terribly objective age, who will own that their children are ne'er-do-wells whereas this was not the case in former times; then every child was good in its parents' eyes. At all events this was a better attitude than the modern one.—Nevertheless we do get a feeling of tragedy if we receive as a gift from spiritual worlds, and as a manifestation of the highest, a difficult child. But we must live through this feeling of tragedy. For this very feeling of tragedy will help us over the rocks and crags of education. If we can feel thankfulness even for a naughty child, and feel the tragedy of it, and can rouse ourselves to overcome this feeling of tragedy we shall then be in a position to feel a right gratitude to the divine world; for we must learn to perceive how what is bad can also be a divine thing,—though this is a very complicated matter. Gratitude must permeate teachers and educators of children throughout the period up to the change of teeth, it must be their fundamental mood. Then we come to that part of a child's development which is based principally on the rhythmic system, in which, as we have seen, we must work artistically in education. This we shall never achieve unless we can join to the religious attitude we have towards the child a love of our educational activity; we must saturate our educational practice with love. Between the Change of Teeth and Puberty nothing that is not born of Love for the Educational Deed itself has any effect on the child. We must say to ourselves with regard to the child: clever a teacher or educator may be, the child reveals to us in his life infinitely significant spiritual and divine things. But we, on our part, must surround with love the spiritual deed we do for the child in education. Hence there must be no pedagogy and didactics of a purely intellectual kind, but only such guidance as can help the teacher to carry out his education with loving enthusiasm. In the Waldorf School what a teacher is is far more important than any technical ability he may have acquired in an intellectual way. The important thing is that the teacher should not only be able to love the child but to love the method he uses, to love his whole procedure. Only to love the children does not suffice for a teacher. To love teaching, to love educating, and love it with objectivity—this constitutes the spiritual foundation of spiritual, moral and physical education. And if we can acquire this right love for education, for teaching, we shall be able so to develop the child up to the age of puberty that by that time we can really hand him over to freedom, to the free use of his own intelligence. If we have received the child in religious reverence, if we have educated him in love up to the time of puberty, then our proper course after this will be to leave the youth's spirit free, and to hold intercourse with him on terms of equality. We aim,—that is not to touch the spirit but to let it be awakened. When the child reaches puberty we shall best attain our aim of giving the child over to free use of his intellectual and spiritual powers if we respect the spirit and say to ourselves: you can remove hindrances from the spirit, physical hindrances and also, up to a point, hindrances of the soul. What the spirit has to learn it learns because you have removed the impediments. If we remove impediments the spirit will develop in contact with life itself even in very early youth. Our rightful place as educators is to be removers of hindrances. Hence we must see to it that we do not make the children into copies of ourselves, that we do not seek forcibly and tyrannically to perpetuate what was in ourselves in those who in the natural course of things develop beyond us. Each child in every age brings something new into the world from divine regions, and it is our task as educators to remove bodily and psychical obstacles out of its way; to remove hindrances so that his spirit may enter in full freedom into life. These then must be regarded as the three golden rules of the art of education, rules which must imbue the teacher's whole attitude and all the impulse of his work. The golden rules which must be embraced by the teacher's whole being, not held as theory, are: reverent gratitude to the world in the person of the child which we contemplate every day, for the child presents a problem set us by divine worlds: Thankfulness to the universe. Love for what we have to do with the child. Respect for the freedom of the child—a freedom we must not endanger; for it is to this freedom we educate the child, that he may stand in freedom in the world at our side. |

| 324. Anthroposophy and Science: Lecture IV

19 Mar 1921, Stuttgart Translated by Walter Stuber, Mark Gardner Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| We are quite clear that the strength of our soul which brings these memory pictures to consciousness is related to our ordinary bright, clear power of understanding. It is not itself the power of understanding, but it is related to it. One can say: What we have been striving to attain—that our consciousness will be illuminated by this imaginative cognition in all our activities as it is in mathematical activity—happens for us when we come to these memory pictures. |

| And if we search for the factors through which we have changed inwardly, we will find the following: We may notice first of all what has happened to our physical organism—for this is always changing. In the first half of life it changes progressively through growth; in the second half it is changing through regression. |

| 324. Anthroposophy and Science: Lecture IV

19 Mar 1921, Stuttgart Translated by Walter Stuber, Mark Gardner Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

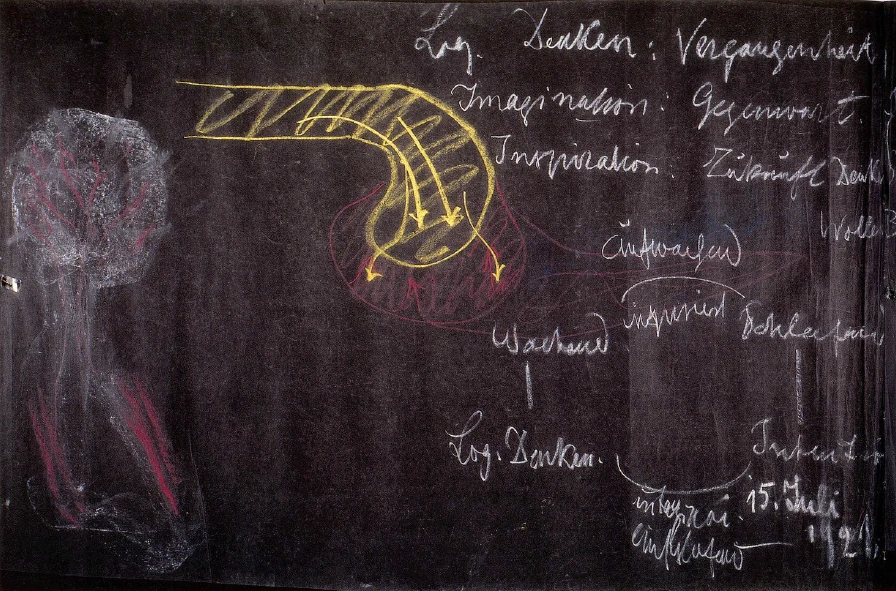

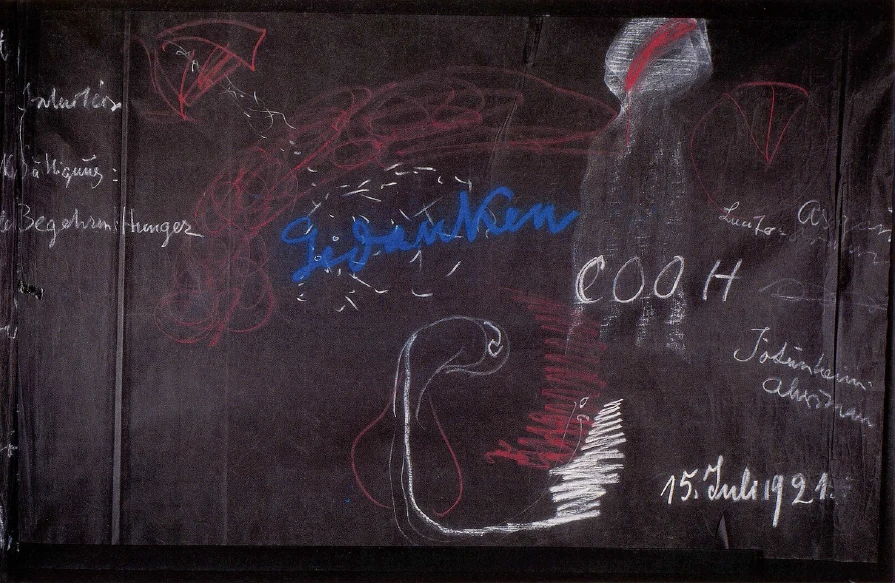

Yesterday I tried to show how, by developing the ability to form imaginative vision, it is possible to gain a different kind of insight into human sense perception than can be gained when we approach it with the logic of the mind. I emphasized especially that this imaginative picturing that lives in the soul—as I said, I will describe its development in due course—has to be built up the way mathematical imagery is built up, the way mathematical constructs are developed, analyzed, and so on. From this, the rest of what I said will also be clear: how we apply the results of our inner mathematical activity to the outer mineral-physical realm; and how in a similar way we apply our imaginative activity to the human senses. In this way we may know what takes place in those "gulfs"—as I called them yesterday—which the physical sense world sends into the human organism. The fact is that with the development of such an imaginative faculty and of knowledge of the real nature of the senses—of what is mainly the head organization—we also gain something else. We become able, for example, to form mental pictures of the plant kingdom. I indicated this yesterday. When we use only spatial and algebraic mathematics to approach plant growth and plant formation, we do not find that this mathematical form of consciousness is able to penetrate into the plant kingdom as it can penetrate into the mineral kingdom. When on the other hand we have developed imaginative cognition, at first just inwardly, then we become able to form mental images applicable to the plant kingdom just as we found it possible with the mineral kingdom. At this point, however, something peculiar appears: we now approach the plant world in such a way that the individual plant appears to us as only part of a great whole. In this way, for the first time we have a clear picture of what the plant nature in the earthly world really is. The picture we receive allows us to see the entire plant kingdom of the earth forming a complete unity with the earth-world. This is given purely empirically to the imaginative view. Of course, with our physical make-up we cannot possibly hold more than part of the earth's plant life in our consciousness. We observe only the plant world of a particular territory. Even if we are botanists, our practical knowledge of the plant world will always remain incomplete in the face of the entire plant world of the earth. This we know by the most simple thought. We know we do not have a whole, we have only part of the whole, something that belongs together with the rest. The impression we have in looking at the partial plant world is very much like being confronted by someone who is completely hidden from view except for a single arm and hand. We know that what is before us is not a complete whole, but just part of a whole, and that this part can only exist by virtue of being connected with the whole. At the same time we arrive at a concept that is completely unlike that of the physicist, mineralogist, or geologist: we see that the forces in the plant world are just as integral a part of the earth as those in the geological realm. Not in the sense of a vague analogy but as a directly perceived truth, the earth becomes a kind of organic being for us—an organic being that has cast off the mineral kingdom in the course of its various stages of development, and has in turn differentiated the plant kingdom. The thoughts I am developing here for you can, of course, be arrived at very easily by mere analogy, as we see happening in the case of Gustav Theodor Fechner. Such conclusions arrived at by analogy have no value for the spiritual science intended here—what we value is direct perception. For this reason it must always be emphasized that in order to speak of the earth as an organism, for example, one must first speak of imaginative mental pictures. For the earth as an integral being reveals itself only to the imaginative faculty, not to the logical intellect with its analogies. There is something else that one acquires in this process, and I wish especially to mention it because it would be most useful to students as regards methodology. In present-day discussions on the subject of thinking and also on how we apprehend the world in general, there is a great lack of clarity. Let us take an example. A crystal is held up to view—a cubic salt crystal, for instance—with the idea of illustrating something or other: perhaps something about its relation to human knowledge, its position in nature as a whole, or something similar. Now it could happen that in the same way that the salt cube is used, a single rose is held up for illustration. The person who holds up the rose feels it is acceptable to ascribe objective life to the rose in the same way as to the salt cube. To someone who does not strive for just a kind of formal knowledge, but who aspires to an experience of reality, it is clear that there is a difference. It is clear that the salt cube has an existence within its own limits. The plucked rose, on the other hand, even on its stem is not living its life as a rose. For it cannot develop independently to the same degree (please note the word) as the salt does. It must develop on the rosebush. The whole bush belongs to the development of the rose; separated from the bush, the rose is not quite real. An isolated rose only appears to have life. I say all this in an effort to be clear. In all observations that we make, we must take care not to theorize about the observations before we have grasped them in their totality. It is only to the entire rosebush that we can attribute an independent existence in the same sense as to the salt cube. When we rise to imaginative mental Images, we acquire the ability to experience reality in a certain completeness.Then what I have just said about the plant world can be accepted. We see it as a whole only if our consciousness is able to apprehend it as a whole, if we can regard everything confronting us separately—all the different families and species—as part of the entire plant organism which covers the earth, or better said, which grows out of the earth. Thus through imaginative mental images one not only gains understanding of the sense world, one also has important inner experiences of knowledge. I would like to speak of these inner experiences of knowledge in purely empirical terms. As human beings we are in a position to look back with our ordinary memory to what took place in our waking life, back to a certain year in our childhood; with our power of memory we can call up one or another event in pictorial form out of the stream of our experiences. Still, we are clearly aware that to do this we must exert a distinct effort to raise individual pictures out of the past stream of time. As this imaginative vision develops further, however, we arrive gradually at a point where time takes on the quality of space. This comes about very gradually. It should not be imagined that the results of something like imaginative vision come all at once. It is pointless to think that the acquisition of the imaginative method is easier than the methods employed in the clinic, the observatory, and so on. Both require years of work: one, mental work; the other, inner work in the soul. The result of this inner work is that the individual pictorial experiences join one another. At this point, time—which we usually experience as “running” when we look over the course of our experiences and draw up one or another memory experience—now time, at least to some extent, becomes spatial to us. All that we have lived through in life—almost from birth—comes together in a meaningful memory picture. Through this exertion of imaginative life, of “looking back,” of remembering back, individual moments appear before the soul. These moments are more than a mere remembering. We have a subjective experience of viewing our life lived here on earth. This, as I said, is a practical result of imaginative mental imaging. What kind of inner experience arises parallel to this inner viewing, this panorama of our experiences? We are quite clear that the strength of our soul which brings these memory pictures to consciousness is related to our ordinary bright, clear power of understanding. It is not itself the power of understanding, but it is related to it. One can say: What we have been striving to attain—that our consciousness will be illuminated by this imaginative cognition in all our activities as it is in mathematical activity—happens for us when we come to these memory pictures. We have images and we hold them as tightly as we hold the content of our intellect. Thereby we come to a definite kind of self-knowledge, a knowledge of how the power of understanding works. For we do not merely look back at our life: our life presents itself to us in mirror images. It shows itself in such a way that this comparison with a mirror really holds true. We can extend the comparison and speak of understanding reflected images in a mirror by applying optical laws. Similarly, when we come to inner imaginative perceptions, we can recognize the power of the soul that we usually think of as our mental capacity becoming enhanced, so that we experience our intellect creating not only abstract pictures but concrete pictures of our experiences. At first a kind of subjective difficulty arises, but once we understand it we can proceed. We experience clarity as in mathematics when we experience these pictures. But the feeling of being free—not in a behavioral sense, but in one's intellectual activity—is not present in this kind of imagining. Please do not misunderstand me. The entire imaginative activity is just as voluntary as our ordinary intellectual activity. The difference is that in intellectual activity one always has a subjective experience (I say "experience" because it is more than a mere sensation), one is really in a realm of imagery, a realm that means nothing from the point of view of the outer world. We do not have this feeling in relation to the content of the imaginative world. We have the very definite experience that what we are producing in the form of imaginations is at the same time really there. We find ourselves living and weaving in a reality. To be sure, at first this is a reality which does not have an especially strong grip on us and yet we can really feel it. What we can gather from this reality, what we become aware of as we think back from our life panorama to the inner activity that created it, acquaints us inwardly, "mathematically," with something that is similar to the formative force of the human being. Just as mathematical mental images match and explain outer physical-mineral reality, so this something coincides with what is contained in the human formative force or growth force. (It also coincides with the formative force of other living beings, but I will not speak of that now.) We begin to see a certain inner relation between something that lives purely in the soul—namely, imagination—and something that weaves through the human being as the force of growth, the force that makes a child grow into an adult, that makes limbs grow larger, that permeates the human being as an organizing power. In short, we experience what is really active in the growth principle of the human being. This insight appears first in one definite area: namely, the nerves. The life panorama and the experiences described in connection with it give us insight at first into the growth principle in the human nerve organism—that is, the creative principle which continues inward in the nerve-sense organism. We receive a mental picture of an imaginative kind that enables us to begin to understand what our sense organs actually represent. This also gives us the possibility of seeing the entire nervous system as a synthetic sense organ that is in the process of becoming, and as embracing the present sense organs. We learn to realize that at birth, though our sense organs are not fully mature, they are complete with regard to their inner forces; this may be evident from the way I spoke about the relation of imagination to the sense world. At the same time we can see that what lives in our nerve organism is permeated by the same force as are the sense organs, but that it is in the process of becoming. It is really one large sense organ in the process of becoming. This image comes to us as a real perception. The different senses as they open outward and continue inward in the nerve organism—during our whole life up to a certain age—are organized by the power we have come to know in imagination. You see what we are striving to accomplish. We wish to make transparent the forces that work in the human being which would otherwise remain spiritually opaque. For what does the human being know of the way in which these forces are active within him? Something that cannot be mastered by ordinary knowledge, something that can be characterized as ordinarily opaque to the soul and spirit, now begins to be clear. One has the possibility, through a higher kind of qualitative mathematics—if I may use such a phrase—of penetrating the world of the senses and the world of our nerve organism. One might think that when we reach this point we would become arrogant or immodest, but just the contrary, we learn true modesty through knowledge of the human being. For what I have described to you in a very few words is really acquired over a long period of time. For one, the knowledge comes quickly; for another, much more slowly. And often someone who applies the methods of spiritual research with patient inner work is surprised by the extraordinary results. The results that such inner work brings to light, if they are properly described, can be grasped by a healthy human understanding. But to draw these results forth from the recesses of the soul requires persistent and energetic soul work. And what especially teaches us modesty is the recognition that after much hard work, the results of imaginative cognition acquaint us only with our nerve-sense organism. We can realize how shrouded in darkness is the rest of the human organism. Then, however, to reach beyond mere self-knowledge regarding the nerve-sense system, we must attain a higher level of knowledge. (The word "higher" is of course just a term.) Above all I must emphasize (I will go into it in more detail later) that the attainment of imaginative knowledge is based on meditation—not a confused, but a clear methodically-exercised meditation (to repeat the phrase I used in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment), in which over and over again we set before our soul easily surveyable images. What is essential is that they shall be easy to view as a well-defined whole, not some vague memories, reminiscences or the like. Vague memories would lead us away from a clear mathematical type of experience. Easily pictured mental images are required, and preferably symbolic images, for these are most easily viewed as a whole. The important thing is what we experience in our soul through these images. We seek to bring them into clear consciousness in such a manner that they are like a clear memory image. Thus through voluntary activity mental images we have evoked are taken into our soul in the same way that we take memory images into the soul. In a way, we imitate what happens in our activity of remembering. In remembering, certain experiences are continually being made into pictures. Our aim is to get behind this activity of the human soul; how we do this, I will describe in due course. In our effort to get behind the way remembering takes place, we gain the ability to hold easily-surveyable images in our consciousness (just as we hold memory images) for a certain length of time. As we become used to this activity, we are able to extend the time from a few seconds to minutes. The particular images themselves are of no importance. What is important is that through the effort of holding these self-chosen images, we develop a certain inner power of soul. We can compare the development of the muscles of the arm through exertion to the way certain soul forces are strengthened when mental images (of the kind I have described) are repeatedly held in our consciousness by voluntary effort. The soul must really exert itself to bring this about, and it is this exertion of soul that is crucial. As we practice on the mental images we ourselves have made, something begins to appear in us that is the power of imagination. This power is developed similarly to the power of memory, but it is not to be confused with the power of memory. We will come to see that what we conceive of as imaginations (we have already partly described this) are in fact outer realities, and not just our own experiences as is the case with memory images. That is the basic difference between imaginations and memory images. Memory images reproduce our own experiences in pictorial form, while imaginations, although they arise in the same way as memory images, show through their content that they do not refer merely to our own experiences but can refer to phenomena in the world that are completely objective. So you see, through the further development of the memory capacity, we form the imaginative power of the soul. And now, just as the power of remembering can be further developed, so it is also possible to develop another capacity. It will seem almost comical to you when I name it—but the further development of this capacity is more difficult than that of memory. In ordinary life there are certain powers by which we remember, but also by which we forget. It seems sometimes that we do not need to exert ourselves in order to forget. But the situation changes when we have developed the power of memory in meditation. For oddly enough, this power to hold onto certain imaginations brings it about that the imaginations want to remain in our consciousness. Once there, they are not so easily got rid of—they assert themselves. This fact is connected with what I said earlier, that in this situation we have to deal with actually dwelling in a reality. The reality makes itself felt; it asserts itself and wishes to remain. We succeeded in forming the power of imagination (in a manner modeled on mathematical thought); now through further exertion we must be able voluntarily to throw these imaginative pictures out of our consciousness. This capacity of the voluntarily developed "enhanced forgetting" must be especially cultivated. In the forming of these inner cognitive powers—enhanced memory and enhanced forgetting—we must be careful to avoid causing actual harm to the soul. However, just to point out the dangers involved would be like forbidding certain experiments in a laboratory for the reason that something might explode someday. I myself once had a professor of chemistry at the university who had lost an eye while conducting an experiment. Happenings of this nature are of course not a valid reason for preventing the development of certain methods. I think I can correctly say that if all the precautionary measures are applied which I have described in my books regarding the inner development of soul forces, then dangers cannot arise for the soul life. To continue—if we do not develop the capacity to obliterate the imaginative pictures again, then there is a real danger that we could be tethered to what we have given rise to in our meditations. If this happened, we would not be able to go further. The development of enhanced forgetting is really necessary for the next stage. There is a certain way in which we can help ourselves achieve this enhanced power of forgetting. Perhaps those who are involved in any of the present-day epistemological studies will find this discussion quite dilettante and I am fully aware of all the objections, but I am obliged to present the facts as they happen to be. So—to continue—one can gain help in enhancing the power of forgetting if we further develop, through self-discipline, a quality which appears in ordinary life as the ability to love. Naturally it can be said: love is not a cognitive power, it does not concern knowledge. Perhaps this is true today because of the way cognition is understood. But here it is not a matter of keeping the power of love just as it appears in ordinary life. Here the power to love is to be developed further through work an oneself. We can achieve this by keeping the following in mind. Is it not so?—living our lives as human beings, we must admit that with each passing year we have actually become a slightly different person. When we compare ourselves at a certain age with what we were, say, ten years earlier—if we are honest—we are sure to find that certain things have changed in the course of time. The content of our soul life has changed—not just the particular form of our thoughts, feelings, or life of will, but the whole make-up of our soul life. We have become a different person “inside.” And if we search for the factors through which we have changed inwardly, we will find the following: We may notice first of all what has happened to our physical organism—for this is always changing. In the first half of life it changes progressively through growth; in the second half it is changing through regression. Then we must look at our outer experiences: what confronts us as our own mental world; all those things that leave pain, suffering, pleasure, and joy in the soul; the forces we have tried to develop in our will life. These are the things that make us a different person again and again in the course of life. If we want to be honest about what is really taking place, we have to say we are just swimming along in the current of life. But whoever wishes to become a spiritual scientist must take his development in hand through a certain self-discipline. He might, for instance, take a habit—little habits are sometimes of tremendous importance—and within a certain time transform it through conscious work. In this way we can transform ourselves in the course of our life. We are transformed through being in the current of life, as well as through the work we do on ourselves with full consciousness. Then when we observe our life panorama, we can see what has changed in our life as a result of this self-discipline. This works back in a remarkable way on our soul life. It does not have the effect of enhancing our egotism, rather it enhances our power to love. We become more and more able to embrace the outer world with love, to enter deeply into the outer world. Only someone who has made efforts in such self-discipline can judge what this means. If one has made such efforts, one can appreciate what it means to have the thoughts we form about some process or some thing accompanied by the results of such self-discipline. We enter with a much stronger personal involvement into whatever our thoughts penetrate. We even enter into the physical-mineral world with a certain power of love—that world which if approached only mathematically leaves us indifferent. We feel clearly the difference between penetrating the world with just our weak power of mental imaging, and penetrating it with a developed power of love. You may take offense at what I am saying about the developed power of love: you may want to assert that the power of love has no place in a quest for knowledge of the outer world, that the only correct objective knowledge is that which is obtained by logical intellectual activity. Certainly there is need for a faculty that can penetrate the phenomena of the outer world by means of the bare sober intellect alone, excluding all other powers of the soul. But the outer world will not give us its all if we try to get it in this manner. The world will only give us its all if we approach it with a power of love that strengthens the mind's mental activity. After all, it is not a matter of commanding and expecting that nature will unveil herself to us through certain theories of knowledge. What is really important is to ask: How will nature reveal herself to us? How will she yield her secrets to us? Nature will reveal herself only if we permeate our mental powers with the forces of love. Let me return to the enhancement of forgetting: with the power of love the exercises in forgetting can be practiced with greater force, and the results will be more sure, than without it. By practicing self-discipline, which gives us a greater capacity for love, we are able to experience an enhanced faculty of forgetting, just as surely a part of our volition as the enhanced faculty of remembering. We gain the ability to put something definite, something of positive soul content, in the place of what is normally the end of an experience. Normally when we forget something, this marks the end of some sequence of experiences. Thus in place of what would normally be nothing, we are able to put something positive. In the enhanced power of forgetting, we develop actively what otherwise runs its course passively. When we have come this far, it is as if we had crossed an abyss within ourselves and reached a region of experience through which a new existence flows toward us. And it is really so. Up to this point we have had our imaginations. If in these imaginations we remain human beings equipped with a mathematical attitude of soul, and are not fools, we will see quite clearly that in this imaginative world we have pictures. The physiologists may argue whether or not what our senses give us are pictures or reality. (I have dealt with this question in my Riddles of Philosophy.) The fact is, we are well aware that these are pictures, pictures that point to a reality, but still they are just pictures. Indeed, to achieve a healthy experience in this region we must know that they are pictures—images—confronting us. However, at the moment when we experience something of the enhanced power of forgetting, these images fill with something coming from the other side of life, so to say. They fill with spiritual reality. And we go to meet this reality. We begin, as it were, to have perceptions of the other side of life. Just as through our senses we perceive one side of life, the physical-sensible side, so we learn to look toward the other side and become aware of a spiritual reality flowing into the images of imaginative life. This flowing of spiritual reality into the depth of our soul this is what in my book Knowledge of the Higher Worlds and its Attainment I have called “inspiration.” Please do not take exception to the name—just listen to how the word is being used. Do not try to remember instances where you have met the word before. We have to find words for what we want to say, and often we must use words that already have older meanings. So for the phenomenon just described, I have chosen the word inspiration. Through developing inspiration we finally gain insight into the human rhythmic system, which is bound up in a certain way with the realm of feeling. This leads us to something I must emphasize: the method leading to inspiration which I have just described can actually be followed only by modern man. In earlier periods of human evolution, this faculty was developed more instinctively—for example, in the Indian yoga system. This, however, is not renewable in our age. It goes against the stream of history. And in the spiritual-scientific sense, one could be called a dilettante if one wanted to renew the yoga system in these modern times. Yoga set into motion certain human forces that were appropriate only for an earlier stage of human evolution. It had to do with the development of certain rhythmic processes, with conscious respiratory processes. By breathing in a certain manner, the yogi worked to develop in a physical way what modern man must develop in a soul-spiritual way—as I have described. Nevertheless, there is something similar in the instinctive inspiration we find running through the Vedanta philosophy and what we achieve through fully conscious inspiration. The way we choose to achieve this, leads us through what I have described. As modern human beings, we approach this from above downwards, so to say. Purely through soul-spiritual exercises we work to develop the power within us that then finds its way in to the rhythmic system as inspiration. The Indian worked to find his way into the rhythmic system directly through yoga breathing. He took the physical organism as his starting-point; we take the soul-spiritual being as ours. Both ways aim to affect the human being in his middle system, the rhythmic system. We shall see how what we are given in imaginative cognition (which combines the sense system and nervous system) is in fact enhanced when we penetrate the rhythmic system through inspiration. We shall also see how the ancient, more childlike, instinctive forms of higher knowledge (for example, yoga) come to new life in the present day in the consciously free human being. Next time I will speak further on the relation of the earlier yoga development of the rhythmic system and the modern approach which leads through inner soul-spiritual work to inspiration. |

| 68d. The Nature of Man in the Light of Spiritual Science: The Course of Human Life from the Standpoint of Spiritual Science

18 Nov 1908, Prague Rudolf Steiner |

|---|

| In a similar way, we also arrive at a solution to the relationship between man, woman and child... It will not be difficult for us to understand the child's relationship to man and woman if we remember that even in sleep, what emerges from the physical principle as a spiritual part of the human being is sexless. |

| On the contrary, this spiritual connection between parents and children would be further strengthened and intensified. Why should certain parents have this child in particular? Because it is this child that wants to go to these parents and be born with and from them. Hence the individuality in the feelings of love, this dawn of love that precedes the birth of a child: love even precedes, even before birth the child loves the parents, even before sexual intercourse and conception by the mother, expressing to the parents that it wants to be born. |

| 68d. The Nature of Man in the Light of Spiritual Science: The Course of Human Life from the Standpoint of Spiritual Science

18 Nov 1908, Prague Rudolf Steiner |

|---|