| 192. The Necessity for New Ways of Spiritual Knowledge: Lecture II

28 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Violet E. Watkin |

|---|

| It could be understood by anyone who had been sent to the Waldorf School from his seventh to his fifteenth year. In that school the forces of his soul would have been healthily developed through methods which correspond to reality, and then, if he had gone to a more advanced school, the elasticity of' his soul forces would have enabled him to absorb what people ordinarily begin to learn after the age of fifteen. |

| I have called attention to these matters in the article which will appear in the next number of the Waldorf magazine treating them from several different points of view. I have intimated that we can no longer today be satisfied with pedagogics modelled as they often are in perfectly good faith and with the best will in the world. |

| 192. The Necessity for New Ways of Spiritual Knowledge: Lecture II

28 Sep 1919, Stuttgart Translated by Violet E. Watkin |

|---|

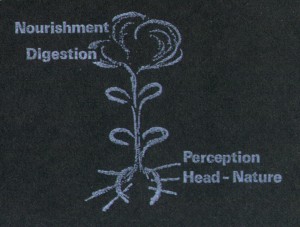

The best way to make ourselves familiar with ideas which can lead us, as men, into the spiritual world,is to try to obtain information through comparison of different facts which face us in the world. What I would like to speak about today will be best explained if I start with such a comparison, i.e.—if I compare the consciousness which our present humanity should in accordance with the mission of our epoch, attain with earlier stages of consciousness attained by evolving humanity. Just think yourselves back to the consciousness of the Greeks, to the ordinary consciousness which the Greeks had of Space. (Naturally I mean the consciousness of Space in a wide sense). You will realise without difficulty that in the consciousness of Space which the Greeks possessed only a portion of Europe was comprised—namely his own land and what bordered on it, a part of Asia and a portion of Africa, and that beyond this definitely limited region, the world was a kind of vague, indefinite quantity It might be said that what formed the horizon of the Greek's consciousness was the boundary of a something which was a vague infinity, at least to his consciousness. And this consciousness of the ancient Greek can be called (although the expression is naturally rather rough and ready, as such expressions always are because the consciousness of language is not adapted to express such things)—this consciousness which the Greek possessed may be called a land, or territorial consciousness. Now you know that the essential feature about the consciousness of humanity in the forward evolution of modern times has been that this territorial consciousness as it were, has developed into an Earth consciousness, that the surface of the Earth as it were, has shut itself off within definite boundaries. As a result of the disclosures of modern history man has imagined the surface of the Earth to be of a spherical shape. Speaking for the moment from the point of view of universal history, it may be said that simultaneously with the emergence of this Earth consciousness as a development out of a territorial consciousness, a panorama of what was outside and beyond the Earth came to be built up, a mathematical-geometrical panorama. The Copernican world-conception arose, and men have conceived of that which is outside and beyond the Earth in Space, in terms of mathematics, of geometry and of mechanics. The Copernican-Newtonian world-conception is, in its essential feature is a mathematical-mechanical picture of the world. Now, for every really thinking man, the question must naturally arise as to whether this mathematical-mechanical picture includes all that there is to be said about that which is beyond the Earth and can be perceived b by men in Space? It obviously does not include it all,,any more than the case when the old Greek confined himself as it were within the land or territory bounded by the horizon of his consciousness, and constructed what was beyond this, in phantasies. Of course the modern man does not clothe that which is beyond the Earth in such poetic phantasy as was the case with the ancient Greek with reference to what lay outside the territorial region comprised with in his consciousness, but the modern man encloses it in mathematical phantasy. Phantasy it is, none the leer for being mathematical. The essential feature in the attitude adapted by humanity in general of the present day is this; to conceive of the Earth as s great sphere in universal space, and to embrace what is beyond the Earth by mathematical and mechanical concepts, which for men who think very accurately, are merely mathematical and nothing else. The concepts which have been invented about all kinds of gravitational forces have been to-day abandoned by more thoughtful men and the world picture of what is beyond the Earth, is really only conceived of in terms of mathematics. If we take all that we have been considering, during the course of many years, from the standpoint of spiritual science, the question must arise as to whether the time is ripe for this super-terrestrial concept of space, this mathematical and mechanical concept of space, to be ensouled by something else, by something empirical, something that can be experienced. For this mathematical-mechanical concept of Space is not empirical in any sense; the space-concept of Copernicus, Kepler, Newton, is something that has been invented, devised, built up from a comparatively small number of observations. And you will realise since there is no possibility of investigating what is beyond the Earth with physical means that such an investigation can only come to pass by means of spiritual science And that it can do to-day. The mathematical-mechanical conception yields no really human factor in this picture; it simply says something to us in abstractions, which do not touch the substantial reality which we postulate. Everything that physics an astrophysics have to tell us today about the super-terrestrial universe, is cold, barren and without any real content. As a matter of fact we are just at that point of time when it is impossible for human evolution to advance any further if we do not progress beyond a concept of the world that is merely mathematical and mechanical. Just as the old Greek had a territorial, or a land consciousness, and man since the beginning of what is called the modern historical epoch, has developed an Earth consciousness, so from now onwards, there must be an expansion to a universal or cosmic consciousness. And today I would like to devote the hour during which we can consider these things, to certain brief, aphoristical suggestions, as to the nature of this world or cosmic consciousness, which must take the place of a consciousness which merely embraces the Earth. Of course a very great deal will have to be done in the future if we are to collect in more exact detail proofs and verifications of that which I am going to put before you today in a kind of aphoristical outline. You know that the investigations of Spiritual Science are based up-an perceptions of the soul,and in my book An Outline of Occult Science a considerable amount of knowledge gained in that way,is given out. In that Look I gave as mush as is necessary for the general consciousness of humanity at the present time, but it must be extended; what is to be found in that book must be deepened and widened. Now with reference to the coming cosmic or universal consciousness, we are, if I may make a comparison, in the position of someone who is travelling in a railway train. He looks out through the window of the carriage and gets accustomed to the idea that he sitting still an his seat. He forgets that the train is itself moving forward. The forward movement which he himself makes with the train, is something that he forgets. He only takes into consideration the movements which he makes, when he gets up, for instance, and in relation to other men who are likewise sitting in the train, changes his position. Now, what such a traveller experiences is something that is very limited in scope, and restricted, and it can be extended by the fact of a break in the journey at some town or other. What he has experienced in the train is not, of course, changed, but the content of his consciousness is increased every time he gets out of the train at some town and experiences what is possible in just that particular place. This is all summed up, as it were, into the content of his journey, and something concrete emerges out of the abstract idea of the journey. The travellers' inner knowledge of the experiences he has had in the different towns is a guarantee that he has gone some distance and has entered into a different set of circumstances. Through the experiences which he has had, he knows that he was not standing still and that he was only able to maintain the illusion of being at rest so long as he remained in the train itself. Now this is something entirely different from what is often said in discussions on the Copernican world-conception. Of course on such occasions mention is made of all kinds of illusions under which man labours, for example, the illusion that he believes to be standing still on the earth, whereas as a matter of fact, he moves together with it, since it is itself moving. But what I mean here is not that. I want to point out something else, namely that man can acquire certain inner knowledge in the course of his life, and especially in the course of experiences which follow one upon each other which are comparable to the experiences which a man has in towns when he gets out of a train and into it again, and so in a certain sense pulls himself up in the inner experiences of his soul, and enters the full content of inner experience at that point. Therein can be found a guarantee, a proof, that while a man is in the world, he travels through space and experiences something which says to him; You, as man, are not at rest, you are in process of taking a real world journey! I want you to be clear in your minds that something like that which is suggested by this parallelism, is the case. The proof of it can of course only be found in the actual experience. Make it clear to yourselves that there can be in the life of the soul, different experiences, in consecutive periods of time which are a guarantee of the fact that one passes on to different points in universal, in cosmic space. We shall afterwards see that this is all said by way of comparison. We shall see too that the difference between the consecutive experiences indicate an element of space which is of much more qualitative a nature than the merely quantitative element which is usually in the mind when Space is spoken of. Anyone who has real inner experience, and not merely the abstract experiences which are frequently brought forward in so external a sense when mystical matters are being talked about, knows quite well that there is something in what I have just mentioned. Whoever has inner experiences is able to notice in the course of his earth life, differences in the content of his soul life at the ages of, say, 30, 40, or 50 years. If he thinks about these inner souls experiences, he knows that he has moved on the world, that he has sought out other places and that his inner, mystical (if I like to use that term) experiences have changed their character. I am here speaking of experiences which are only taken into account by those who do not look upon mysticism in an external, abstract way, but who look upon it as something concrete in inner experiences. The abstract mystic may talk from the age of 25 years, right up to the end of his life, of the “God within him”. But a man who knows how to understand inner experiences as a concrete reality, knows that these inner experiences change their nature and content, as if on a world journey, which is not the same as a tour around the earth. If I may again express myself mystically, we traverse universal space consciously through our inner experiences. But we only do it as it ought to be done, when we reflect upon our relation to the surrounding world in a much more definite fashion than is usually the case. It is quite possible to look upon our relation to the surrounding world in such a way that on the one side we have only our sense perceptions in mind, and on the other our desires, our willing, our deeds, our acts. The fact of holding our sense perceptions in the mind, sets us in definite relationship with the outer world; we perceive through eyes and ears, certain facts of the external world—we are in living intercourse with the outer world. What happens—happens as it were, at the margin of our corporeality. To-day I will not go into certain physiological objections, or those of theories of cognition which could seemingly be brought against what I am saying, because what I want to do is to outline the nature of the consciousness which must be attained in contradistinction to the earth and the territorial consciousness already described. Our sense perceptions then, place us in a certain relationship to external events. And again, when we act, we stand but from the standpoint of another pole of our being in a certain relationship to external events and occurrences. We are involved in them, involved in a real sense, for we have ourselves partly brought them about. Between these two extremes of our life as human beings, is to be found everything which goes on in the field of our consciousness; on the one side there is the relationship to the outer world given us by the senses, and on the other side, by our desires and acts. In that we develop feelings and conceptions of what our senses perceive, we live an inner life. And willing is fashioned from feeling and perceptions which have either deepened or condensed, as it were, into faculties. So that between perception and willing lies that which we psychically experience. But now, what is present in sense perception, is only seemingly a unity. In sense perception we look at the world and it appears to us as something uniform, a unity perceived through the senses. But as a matter of fact within this apparent unity, a duality is contained. For anyone who is capable of real perception, a duality is contained within what seemingly is a unity; there is a continual dying and uprising again. The world without us is in a state of perpetual dying and again coming to birth. In every moment in the world, we live in something that faces death, and out of that death, life continually comes forth again. If you look at a cloud, or anything else in the outer world it appears to you as a unity; but that it is not, The fact is that something is dying in the cloud, and out of this death something is again being born. Out of what comes from the past, there develops something which goes forward into the future. In all that we perceive there is ever contained fuel that is burning away and dying out; and fire that is arising, newly created, passing over as living form into the future. Then through such a training as is given in The Way of Initiation and Initiation and its Result, we learn how to separate these two poles of sense perception from each other, and to perceive actually the phenomena of death and coming to birth, then for the first time the world takes on a real aspect for us. When a man who is trained in the right way observes another man through the senses, he sees in that other man something that is continually dying and something that is continually arising again. Dying—coming to birth; dying—coming to birth, that is what we see when we have trained our powers of observation to some degree. When this continual dying and coming to birth becomes objective to us, when we really see it and do not merely imagine it in an abstract way—when we see continually in a man, a corpse and a child coming into being (and it can be actually seen in this picture)—in that moment we have within our range of vision, the three hierarchies of of the Angels, Archangels and Archai. The world is full of real substance. It is no longer a unity such as we used to see when we look at nature. We cannot observe this dying and coming to birth, this Prana and Shiva of nature, without finding the whole of nature transformed and resolved as it were, into the activities of the spiritual beings of the three Hierarchies immediately above man. And so it is at the other pole of our being. In our deeds and acts there is again a continual dying and arising. But at this pole it is much more difficult to perceive it. A long and arduous training is necessary, but it can be done. And we then are within range of wisdom of the Seraphim, Cherubim and Thrones. Through meditation then, we perceive what is between the two poles: we are able to contemplate that Being Whom, as I have told you, is to be found midway between these two poles. Everything becomes more vital, more living in our epoch as we gradually acquire this way of thinking. But by rising to this height of contemplation, our soul life changes considerably. 'hen we really have got to the point where we see in our surroundings the activities of spiritual beings, then, at the same time we get to a point where we are able concretely to observe the differences in the soul life of the different epochs of which I have already spoken. And then when we have learnt (it is difficult to learn, but it is possible)—to take account of these inner changes in concrete inner experiences—then we see ourselves to be travelling through universal, or cosmic space. And then we know, not by means of external mathematical considerations, not by the sequence of inner experiences, that we together with the earth have changed our position in cosmic space. And then cosmic space becomes a very different thing to the mathematical-mechanical space conceived of by Copernicus, Kepler, and Newton. It becomes something that is inwardly vital and living, We learn to distinguish movement which we make as men in universal space. We learn too, to distinguish a movement which is made from left to right—that is an actual movement which we make with the Earth from another movement which is an ascending one as it were; we realise that in turning, we also ascend in space. Yet a third movement—a “forward” movement I might call it—an onward movement. This is not the same thing as moving an the Earth but is something which is done together with the Earth which can be proved by inner experience. We can prove to ourselves that when we turn from left to right, we ascend and at the same time go forward. So, by inner experience, we observe a threefold movement made, not in relation to some other heavenly body but a movement in an absolute sense in space. Now of course you will say that the present consciousness of humanity is very far away from the conception that man in this sense is a world traveller and that he can quite well prove to himself the reality of this world journey. Yet there is a means whereby such consciousness can be acquired, however far away from these things human consciousness nowadays may be. What I have described is a reality, even if men to-day know nothing about it. Their ignorance can be compared to the belief which may be held by a man in a railway train who imagines that he is sitting still, whereas he is moving forward with the whole train. Now why is this belief general? In the first place the purely mathematical and mechanical Copernican world conception has for the last three or four hundred years had a more lulling to sleep than an enlightening influence an men. I have often said that this purely mathematical-mechanical world conception is really based upon a mistake which is quite fairly obvious. It presents a convenient picture of space but really no more that that. In the well known work of Copernicus about the revolutions of the heavenly bodies in space, three tenets are to be found, but modern science bases itself only an the first two, and takes no account of the third. Copernicus knew something more than what is admitted by modern astronomical science. And this “more” he concealed in his third tenet -but no account is ever taken of that third tenet. The observations made do not agree with the Copernican system, but modern science disregards this. Today when under certain conditions a man investigates empirically where some star or other ought, according to the correct reckoning set forth in the Copernican system to be found at a particular point of time it is not there. But then there is the so-called Beseel correction, and it is applied in order to obtain the right result. The application of this “correction” is only necessary because the third tenet of Copernicus has not been taken into account. Because of this, a kind of convenient mathematical-mechanical world conception or world picture has come into existence during the last three to four hundred years. It is not in accord with many things, but of course today anyone who mentions this fact is put down as a fool! It is scientific to believe that the various facts are quite in accord with each other. Humanity has been lulled to sleep by the Copernican conception of the world with reference to certain facts—facts which are nevertheless substantiated by inner experience. Human consciousness is dulled and in the future men will have to see to it that this state of things does not continue. I have often remarked that men do not wish to understand spiritual science with their own “healthy” sense. This is really only a result of certain educational prejudices which hold sway at the present time. It is very frequently the case nowadays that when the occultist gives out his experiences people say: Oh well, it may be so, but the only people who can know that are those who have gone through a certain “mystical” training as they describe it. Now that is right to a certain degree, but not entirely right. I have repeatedly said that up to a certain point, everyone today can recognise as fact, through his own consciousness what is, for example given in my Outline of Occult Science. There is no need to take it merely an authority. Everyone can understand it by means of an ordinary healthy human intelligence But How? It could be understood by anyone who had been sent to the Waldorf School from his seventh to his fifteenth year. In that school the forces of his soul would have been healthily developed through methods which correspond to reality, and then, if he had gone to a more advanced school, the elasticity of' his soul forces would have enabled him to absorb what people ordinarily begin to learn after the age of fifteen. That would be one way of getting men who would realise that reality is only given by what is substantiated by spiritual science—and that everything else is nonsense. The fact that men will not admit this, does not originate from any impossibility to understand spiritual science without training, but arises because our school education between the seventh and fifteenth years is of such a kind as to kill out and stultify certain forces instead of waking them into activity. It follows that men resist the acceptance of facts given by spiritual science, although they would readily accept many of them if their psychic powers were developed in a healthy way. Powers of the soul which have been developed in a healthy way are not dead and benumbed as appears to be the case in the majority of men of our modern times; they are mobile, fluidic, elastic, and anyone in whom they had been rightly developed between the ages of seven and fifteen would be irritated at the modern way of learning things. Today people are satisfied with many things because certain incorrect theories have made the illusions far greater than they really need be. I have often quoted a characteristic example. Children in their 12th, 13th, and 14th years are told that lightning comes from friction in the clouds and it is admitted at the same time that the clouds are wet. Of course they are; but then when it is a matter of producing the electric spark which is the earthly replica of the lightning, it is found necessary to keep the electrical apparatus and everything belonging to it perfectly dry in order that no water of any kind is present; so that it comes to this—the only thing that is present when the lightning originates, is removed and yet the lightning is the same phenomena as the electric spark! Children and grown up people are quite satisfied to be lulled to sleep with all kinds of hypotheses of this kind. There are innumerable examples of the same kind where people will accept obvious nonsense simply on authority and yet in our days there is much talk of the laying aside of all authority—people say that they are no longer credulous of' authority. Yet as a matter of fact if they had been so credulous it would have been quite impossible for the Marxian-Socialistic world conception to arise in our epoch, for it is far more credulous of authority even than ancient Catholicism! It is today one of the most essential cultural tasks,to overcome that which in so retardative a way interferes with men's powers of understanding—and to substitute for the present system a healthy educational organisation. It is one of the most important social talks to work for the removal of impediments to human understanding. And then men will not be so obstinate and perverse about accepting what spiritual science has to say; they will rather be irritated by much that orthodox science has to say today, that is if their development has been a healthy one. They will very soon learn to see through all the contradictions. There is instinctive opposition nowadays to the establishment of healthy educational conditions, for it is felt that if they were to be established the authority of modern science would be undermined in a drastic way. It is essential that fluidic soul forces should again be produced in humanity and they will emerge quite naturally as a result of the knowledge which Spiritual Science is able to impart. As a result of these elastic soul forces humanity would be able to understand what is meant when it is said that man is within a movement which is absolute; men would furthermore understand how a world consciousness can grow out of an earth consciousness. To speak in pictures for a moment, but the picture is really a good one—it is as if a man learns to feel himself as a traveller through universal space—a traveller whose movement consists of a rotation combined with a forward movement and a movement from below upwards, If we sketch the result of these movements—moving upwards in rotation, moving forward in this upward spiral movement—the curve will represent the path of the earth through cosmic space, not mathematically and dynamically as it is built up through the Copernican- Newtonian world conception—but as a result of inner observation. This is the way in which it ought to be arrived at for then we get something that is not abstract like the Copernican-Newtonian world conception, but very concrete—something that is actually super-sensible experienced empirically, if one may be allowed to use this tautology. The importance of this kind of cosmic consciousness does not lie in the fact that through it a man begins to feel things more in accordance with the truth than is now the case when he believes the Copernican world conception and the path of the earth as conceived of by it, to be correct, but very much else is dependent upon it. I makes on inwardly a different man. A man learns to feel himself not merely a citizen of the Earth but of the Universe, of the Cosmos. The world expands,as it were, for anyone who comes near the forces which are actually operative in these movements. In the rotary movement from left to right are to be perceived the activities of the Angels; in the ascent from below upwards the activities of the Archangels; and by the advance in universal space forward are to be seen to movement of the Archai, the forces of the Time Spirits. By taking up into his consciousness this absolute movement through the cosmos man turns his gaze into a spiritual space and becomes aware of the fact that physical space is only an abstract image of this concrete, spiritual space, in which the activities of the higher Hierarchies are to be found. It follows from what I have just said that such a consciousness is connected with something else. Anyone who has an idea that there is something of this kind bound up with the real being of man must necessarily realise what terrible harm is performed by modern education in that it allows certain forces to be paralysed in our children up to their fifteenth year and they then as students develop into something that is a natural result of these paralysed forces. It follows that young people between the ages of 15 and 21 absorb things that are not at all what the present time demands. And in their souls there exists things that are very different from what they ought to be. I assure you that by giving unctuous exhortations to children up to fifteen years old and then again later at an age when people used to have ideals as young men and girls of 20 years of age—you will attain absolutely nothing at all; or at least only that the young people at our Universities and High Schools become what they are today—which there is no need for me to describe any further! The only way to obtain real results is by giving free play to forces which should be active during student days, which nowadays are simply paralysed. Education today is a problem touching the whole of humanity. It is a problem not for arbitrary ideals, but for the whole of humanity, a problem which must be understood in the light of the very deepest demands of the present time. At most today men have a presentiment that muck ought to be different—let us say, for example, in medicine, possibly also in the realm of law and judicial matters, but that feeling when it arises is promptly squashed by the lawyers! Men have a kind of feeling that many things are not what they ought to be, but that they cannot be changed. The aim of mankind must be directed at the right period of life to the awakening and not to the paralysing of forces within them. The life period between the seventh and fifteenth years is not there for nothing. During this period, perfectly definite forces out of human nature which must be reckoned with when it is a question of education or giving instruction at this time of life. When anyone has this in view in education it is a very different thing to working arbitrarily: without any such aim. Certain things will be observed which today pass by entirely unnoticed. I have called attention to these matters in the article which will appear in the next number of the Waldorf magazine treating them from several different points of view. I have intimated that we can no longer today be satisfied with pedagogics modelled as they often are in perfectly good faith and with the best will in the world. Certain methods and principles and standards are drawn up—in good will perhaps, but without any real insight—and it is believed that these standards of pedagogics can be learnt. Herbart and his followers have this belief to-day that just by “learning” pedagogy it is possible to become a good teacher. Now even in the case where a set of standard rules is the most perfect imaginable—the rules are almost as worthless for teaching as a well-written book on aesthetics is worthless to the artist. It is quite certain that well written books on aesthetics do not make a man into an artist—and a science never makes a true teacher. It is not necessary to learn physiology in order to be able to feed oneself; a man can feed himself by a science that is quite different from physiology. Physiology is there for another purpose and if it is brought into the question of correct feeding, it comes in as a makeshift. It was always a horror to me to meet men at table who had scales near them in order to measure out and weigh every morsel that they put into their mouths and eat at a meal. That is am example of where the science of physiology interferes in a most destructive way in the process of feeding. Ah yes, you may well laugh at that; but those who because of their scientific prejudices feel such a thing to be justifiable, would laugh for quite another reason considering what I have said to you today to be the most god-forsaken dilettantism. He may laugh at these things from diametrically opposite points of view. Well now, a cut and dried system of Pedagogics can never produce real teachers. And why? It is drawn up in such a way that its fundamental rules have to be accepted and then education is of no benefit at all. What is desirable is to forget pedagogics altogether when one goes into a classroom; to forget everything that may be known about academic pedagogics! Every time it should grow naturally out of a wide knowledge of what man and humanity is. Nobody can be trained to be a teacher by the mere fact of learning pedagogy; pedagogy can only be stimulated in men when they have acquired a knowledge of the nature of man. We should disregard pedagogics as a science as it were, and at most regard it as artists regard aesthetics, being quite conscious of the fact that aesthetics and its laws can never teach how to paint. An artist in Munich once said to me when I was speaking to him about aesthetics and Carriere—who was a celebrated authority on the subject: “When we were in the Art School we used to call Carriere ‘an old grunter on aesthetic rhapsodies!’”(Wonnegrunzer). Now it has not occurred to students as yet to give the same kind of appellation to theoretical pedagogics, for the general idea is that in pedagogics it is possible to make use of things which cannot be used in art. But as a matter of fact, the two things are the same. Into pedagogic training there should be brought that element which is to be found in our spiritual teachings—knowledge of Man, insight into the nature of humanity and that is able to stimulate a living relationship with the human being which is developing out of the child. Pedagogy should be born afresh every moment in the teacher; the impulse to teach and instruct in a certain way arises as the immediate result of having any particular child in front of one. This will produce quite a different kind of atmosphere from what prevails in the school room today, just because it is created not by cut and dried rules of education, but because it flows of itself out of life—living life as it were! If education were to arise out of life in this way, then those forces which ought to be present at the age of fifteen will not be paralysed, and a man will enter upon his later life with forces that are fluidic in his soul-forces of a kind which are necessary in order that something similar to what happened at the transition of the Middle Ages to modern times—when territorial consciousness was transformed into an Earth consciousness, may come to pass in our epoch—in order that out of an Earth consciousness there may grow a world consciousness, a cosmic consciousness. Outer experiences will not produce this; it will only come through the development of susceptibility for inner consecutive experiences of the soul. Today man has not the faintest consciousness of the dissimilarity of there souls experiences. Now what is the position to-day? Men are children; they act like children influenced by their environment. Then the child becomes an adult; the concepts become more abstract, the experiences richer; that is the case with everybody. But with the soul it is not the same as is the case with regard to the external bodily part of us. We get a more sharply defined countenance when we reach a certain age; we have no longer the round curves of childhood; we get white hair and wrinkles, and we very often get bald! In short, the external bodily part changes. We cannot, however, say that the inner soul nature changes in this way—at most it gets more and more crammed full—but it does not grow in such a way that it changes from the point of view of thee external world. Old age and childhood have a wrong relationship to each other. Man today has no consciousness of things of which I have often spoken to you; for instance that an old man can bless and that the blessing of an old man has a special significance—a significance which is not there in the case of a middle aged man. Men of today have no consciousness of such things—simply because it is not known in our days that if one is to be able to bless rightly in old age, one must have learnt in childhood how to fold the hands (in prayer or veneration) For the power to bless in old age arises out of the folding of the hands in prayer in childhood. The soul element has the same relationship to blessing and the folding of the hands in prayer as grey hair has to the the hair of childhood. This inner change enters the sphere of knowledge of modern humanity in a very limited sense; but it must do so again to a greater degree. Men must again come to a point where they can understand life in its different metamorphoses. Otherwise we shall never get out of the terrible state of things which, for instance, makes it possible for anyone who is 18 or 19 years old and has a little talent, to become at that age, a Feuilletonist. [A journalist responsible for the critical and literary articles which sometimes appear in a newspaper below the leading articles. The feuilletons are usually divided from the rest of the newspaper by a line.] People who read the feuilletons produced by these men have no idea that they have been written by someone only 18 years old—and take them quite authoritative utterances. But if a man writes feuilletons at the age of 18 he does not develop any further. It also comes about that men when they are only 20 or 21 years old are considered mature enough to go into Parliament, or to become a town councilor! They are supposed to be capable to do this kind of thing. It is in these cases considered to be unnecessary at the age of 40 years to try to be a more accomplished person than was the case at their age of 20, for everything that the world can offer and what can be offered to the world, has already been attained! At the age of 20 one chooses or is chosen and the thing is finished! But men will first understand the wor1d in a concrete sense when they again realise that life is something which undergoes concrete transformation. Then that abstract socialism of which we hear so much today, will disappear and something concrete will take its place. So you see that the growth of a cosmic consciousness out of an earth consciousness will be of great significance, especially because of what is produced in men by their feelings; for the important thing in such matters is not what a man knows but how he feels. There are certain things associated with life which can be understood only when this cosmic or universal consciousness is reached. There is a great deal of abstract talking today about the ages or generations as they follow each other in life. We think something in this way—I mean those of us who have reached a certain age, for I except young people from this; a man has capabilities of a certain kind; he lives in such and such a way; his childhood was spent in such and such a way. People are really very short-lived, for they get angry with children when they do the same things as they did at the same age; they do not understand that children of to-day do the same kind of things as they themselves used to do; they expect those who are now children to be as well behaved as they are as grown up people, and do not realise that good manners and behavious have first to be acquired. But apart from this, there is something else. Men generally imagine that children now must be just the same as they were when they were children—a generation ago; children, who are born now must be just the same as I was in the year 1860! Now that is nonsense. For we are in an absolute sense, further on in cosmic space and those who are babies now are born at a different point of space. Suppose you travel from Stuttgart to another town today—you will have had something to eat in Stuttgart today and tomorrow somewhere else. You cannot have a meal in Stuttgart when you travel. And the children who are born in our time, cannot have the same psychic constitution as those of us who have reached a respectable age had when we were children. We must realise that childhood itself changes. This is connected with our absolute movement in universal space—of which mathematical space is only a schematic image. There is a tendency today to take ever thing in an absolute sense and it is a matter for rejoicing when this is not so. I was recently very pleased in Berlin when a man came to see me who had read—well,what shall I say the “discussions” of the Threefold Commonwealth which appeared under the title of A False Prophet in the paper called Die Hilfe. I do not know whether any of you read that effusion. This man was an American and he said to himself that there was something interesting about it. And he came to see me with Herr Pfarrer Rittlelmayer and explained that in spite of the feeble style, he had realised that it was a matter of interest. Among the questions which he—all of which were quite understandable—was the following, which specially pleased me; “One can see that the Threefold State is necessary for modern times and that it must be put in the place of the old uniform State; is it your opinion that the Threefold Commonwealth is the final and conclusive solution of the social question?” I answered him: “Most assuredly not; but in the course of historical development it has come about that in past centuries the State as a unity has been more in evidence and now the times demand a threefold Commonwealth, a time will come when the Threefold Commonwealth will have to be replaced by something different. That will not however, be for about three or four hundred years and then it will be necessary again to consider what should take place of the Threefold Commonwealth”. Now that is the opposite of chiliastic thought, the opposite to the thought that imagines the kind of empire which has lasted for a thousand years to be right for all time. It is the opposite of thinking which imagines that once a blessed existence is obtained for humanity it must remain for all time. Life in the world is not so easy as that. What is essential is that what is right for a particular epoch should be brought about and then substituted at the right time by what the following epoch demands, That is the essential point, that is organic thinking in contradistinction to mechanical thinking—and mechanical thinking is what holds sway at the present time; men really imagine that there is one absolute right for all time. One thing is right for Stuttgart, another for New York, another for Australia, One thing is right for 1919, another for 2530. I assure you that the evolution of humanity is not so simple as to possess one absolute Right. Things are always right for particular places and for particular times; there must be concrete thinking which arises from the facts and relationships. And that will happed when humanity is conscious of its absolute movement in universal space. a consciousness which, however, can only be induced through inner experiences, through inner life. I have again to-day called your attention to something which should indicate to you how things must be looked at with reference to the penetration by spiritual science of our modern culture. Anyone who understands such matters,will see that humanity's love of ease resists spiritual science, for everything else is far more convenient, far easier, Spiritual science is terribly inconvenient! Spiritual science does not permit of our thinking out a certain condition of things which can remain for ever; it forces us to think out what is good and right for the centuries immediately following, perhaps even for a still shorter period of time. But this cannot be thought out by abstract concepts of the intellect about humanity, but only when a real effort is made to understand the special characteristics of the particular epoch, and to realise thereby what it demands. That may be inconvenient, but that is the reality. Men today like the settle down comfortably into cultural evolution, especially those men whose aim it is to be leaders in it! I will give you an example of the understanding which persons of authority at the present time have of' spiritual science. I won't relate the story in detail in case someone might get offended, but in a certain town a man had occasion to lecture about Anthroposophy in a private High School. He was lecturing about modern world conceptions and he wanted to include an address about Anthroposophy because he considered it historically necessary—you see people try nowadays to be really “all round”. Now how did this man set about it? The plan of the lectures, the programme,was drawn up at the beginning of the tem and a certain hour was allotted to “Anthroposophy” just as in certain hours the subject was Darwinism, a particular hour was set aside for “Steiner's Anthroposophy”. This was all drawn up at the beginning of the term. Now this man, when he put Anthroposophy into the programme, had not the very least idea of what was to be found in a book about Anthroposophy. When the evening for this particular lecture came round, this man went to someone who had my books, and in the morning selected the most important of them in order to get information, in order to be in a position to give his lecture an Anthroposophy in the evening. It is very convenient to familiarize oneself in such a way about a world-conception, and then to give it our authoritatively. Such a thing as this is by no means rare in our modern days, and it deserves to be mentioned. For very, very much of what is said and lectured about and written about in the present day has no greater “depth” than this and it is accepted credulously. Then out of this credulous acceptance it built up what people have in their heads and in their souls about the different world conceptions. We must not close our eyes to facts like this which show the most terrible superficiality, we must be quite clear that to-day it is essential first of all to consider who the person is who is speaking “authoritatively” an certain matters. The stimulation of this consciousness in the present time is more important, my friends, than all the substance of what I am able to tell you; it is a consciousness which makes us realise how terribly necessary it is to consider what degree of depth there is behind that which is given us, and told us. If one speaks of these things of course many people are hurt. And particularly it is said about Anthroposophists and Theosophists that they ought to have more forbearance, to judge with greater kindliness and not to be so critical, because to be so critical hurts people. But one asks oneself whether it is real charity to ignore the fact that such men who acquaint themselves in the morning with what they have to lecture upon in the evening should be let loose in the sphere of education. In questions that arise out of actual life, the important thing is how they are put. It is important to put the questions in the right way, for then only can the right point of view result. I have tried to bring home to you today that earth consciousness must change into a cosmic or universal consciousness just as a territorial consciousness changed into an earth consciousness; but I did this in order to indicate much that in the realm of feeling is essential for the bringing about of healthy relationships in our civilisation of today. And Oh! this must come about. If one could only shake sleepy humanity of modern times into a realisation of this! But it isn't by any means easy nowadays. Much may be said in this direction but men avoid making themselves fundamentally familiar with such a point of view. It is not enough merely to bring forward anthroposophical theories. It is absolutely essential to make one's penetration sharp for what is necessary for our time and not shut oneself up in preconceived ideas, We must open ourselves out toward that which has to be wrestled with, in order that from the point of view of a true charity one may be able to strike actively at the present time. If something is done in this direction by stimulating the souls and hearts of men, more is attained than by the most comprehensive theories imaginable. It makes one's heart bleed to realise the truth of what was said by Herr Molt recently, that there are people today who say: “We would rather be a province of the Allies before we will think of anything like the Threefold Social Organisation”. This attitude is unfortunately widely spread. And a great many other things are connected with this kind of attitude because as a matter of fact another attitude can only arise from a spiritual deepening. Our modern time can only grow to be healthy through such spiritual deepening. |

| 342. Lectures and Courses on Christian Religious Work I: Second Lecture

13 Jun 1921, Stuttgart |

|---|

| The anthroposophical movement – I can say this quite openly – will never fail to support this union, of course; but it would not be good to form ecclesiastical communities out of the anthroposophical 'communities', so to speak. You see, when we founded the Waldorf School - it is not an example, but there is at least a similarity - we did not set out to found a school of world view, a school of anthroposophy, but merely to bring into pedagogy and didactics what can be brought in through anthroposophy. |

| Now, however, it has become clear that, because the first core of the Waldorf School was working-class children, a great many children would have had no religious instruction at all. |

| 342. Lectures and Courses on Christian Religious Work I: Second Lecture

13 Jun 1921, Stuttgart |

|---|